Malignant Renal Tumors in Older Children Experience of the Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Department of Rabat

Abstract

Background: Data on renal tumors in children aged 7 years and older are more limited than those available for younger children. In this older age group, patients more often present with heterogeneous clinical signs and symptoms and a higher proportion of uncommon histological subtypes, although nephroblastoma remains the most frequent diagnosis. This study aims to describe the epidemiological, clinical, and outcome profiles of renal tumors in older children.

Methodology: This is a retrospective descriptive study conducted over a period of 16 years, from January 1, 2006, to January 2022, in the Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Department of Rabat for renal tumors.

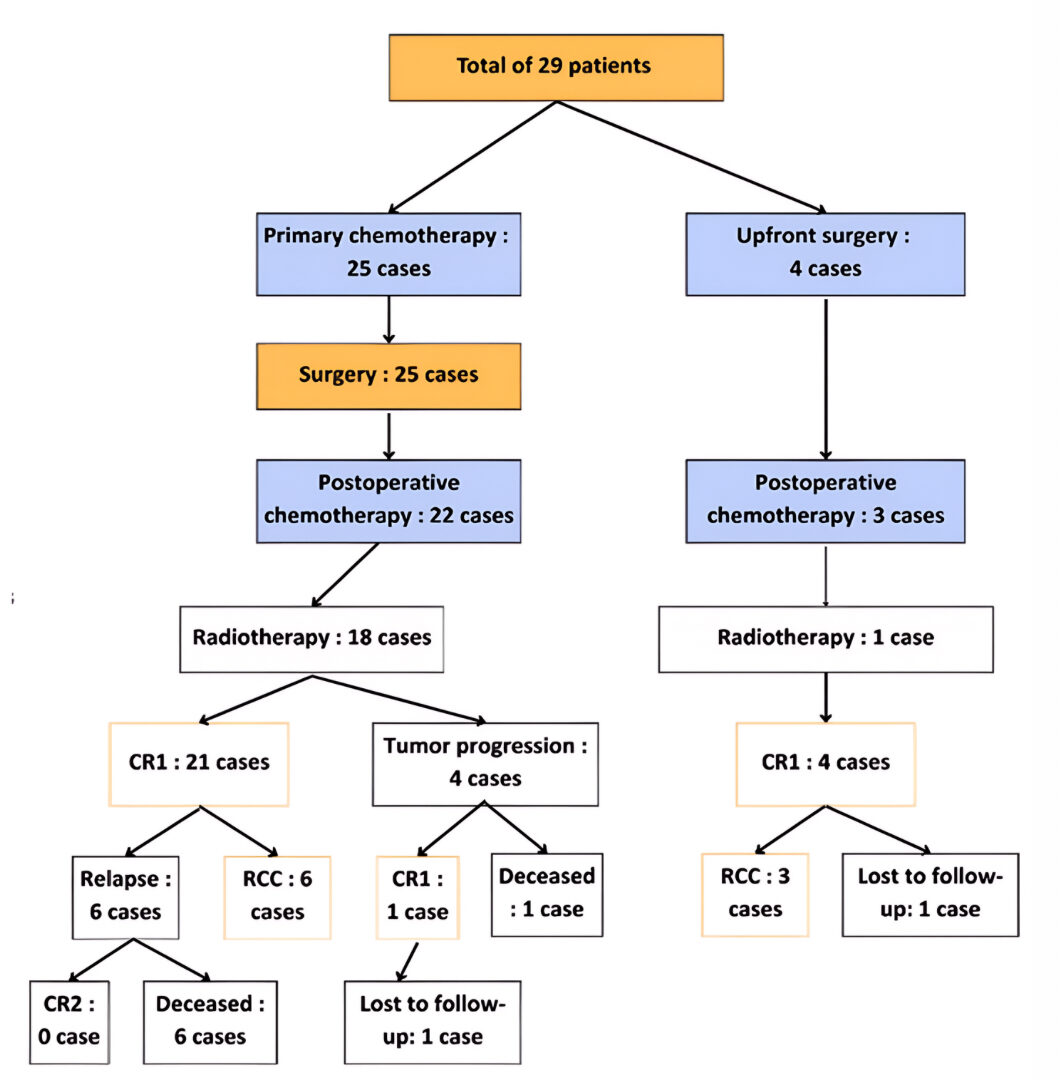

Results: During the study period, a total of 4,569 pediatric cancer cases were recorded, including 350 cases of renal tumors (7.6%), with 29 cases occurring in children aged 7 years and older (8.2%). The median age was 8 years, with extremes ranging from 7 to 15 years. The sex ratio was 0.75. The main reasons for consultation were abdominal distension and pain. Lung metastasis was present in 40% of renal tumor cases at initial presentation. Therapeutic management consisted of preoperative chemotherapy (except for 4 patients who were operated immediately), surgical treatment followed by postoperative chemotherapy in 25 patients, and radiotherapy in 19 patients. Histology revealed 23 cases of nephroblastoma, 4 cases of renal cell carcinoma, and 2 cases of clear cell sarcoma of the kidney. During follow-up, we noted 19 cases of complete remission, 4 cases of tumor progression, 6 cases of relapse, 9 cases of death, and one patient was lost to follow-up.

Conclusion: This study demonstrates that among renal tumors in children aged 7 years and older, Wilms’ tumor is the most common histological type. However, in this age group, it is important to consider other histological diagnoses. The prognosis depends on several factors, hence the importance of early diagnosis.

Keywords: Renal tumors, Child, Age, Treatment, Survival

Introduction

Renal tumors represent one of the most common groups of solid tumors in children, accounting for approximately 7 to 8% of all pediatric cancer cases. Various types of tumors, primarily malignant, are identified within this category1. Older children more frequently present with multiple signs and symptoms and less common histopathologies, although nephroblastoma remains the most prevalent2.

The treatment of malignant renal tumors is multimodal, involving surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy to varying degrees depending on histology and stage. Two distinct approaches exist for the initial management of pediatric renal tumors. Most children in Europe receive preoperative chemotherapy according to the protocols of the International Society of Pediatric Oncology (SIOP) renal tumor study group. In North America, patients undergo initial surgery before chemotherapy administration, following the protocols of the National Wilms Tumor Study (NWTS) and the Children’s Oncology Group (COG). Although these two strategies differ in their initial treatment approach, they yield a similar overall survival (OS) rate of approximately 90%1.

Available data on renal tumors in children aged 7 years and older are less frequent compared to those in younger children1. This study aims to analyze the epidemiological, clinical, histological, and outcome characteristics of children diagnosed with renal tumors at age 7 or older and followed in the pediatric hematology and oncology department of the Children’s Hospital of Rabat.

Methodology

This is a retrospective descriptive study conducted over 16 years (January 2006 – January 2022), involving a cohort of 29 children aged 7 years and older who were followed in the pediatric hematology and oncology department of the Children’s Hospital of Rabat (SHOP) for malignant renal tumors. Data were collected from medical records and hospital registries at SHOP Rabat.

Treatment was based on the GFA Nephro 2005 protocol, which is used in centers affiliated with the Groupe Francophone Africain d’Oncologie Pédiatrique (GFAOP) and follows the recommendations of the International Society of Pediatric Oncology (SIOP) for the therapeutic management of pediatric renal tumors.

The protocol primarily involves preoperative chemotherapy using a combination of two drugs (Vincristine and Actinomycin D), with the addition of Adriamycin in metastatic cases. The number of chemotherapy cycles ranges from 4 (for non-metastatic forms) to 6 (for metastatic forms), followed by surgery, and postoperative chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy adjusted according to histology and stage.

Results

During the study period, a total of 4,569 pediatric cancer cases were recorded, including 350 cases of renal tumors (7.6%), with 29 cases occurring in children aged 7 years and older (8.2%). The median age was 8 years (range: 7–15 years). A slight female predominance was observed, with a sex ratio of 0.75. Familial consanguinity was noted in 9 patients, and a family history of cancer in 8 patients. The time between the onset of clinical symptoms and diagnosis ranged from 6 days to 12 months, with a median delay of one month. The main reasons for consultation were abdominal distension and pain. Hematuria was reported in 5 patients. Clinical examination did not reveal any malformations or anomalies of the external genital organs.

Imaging confirmed that all renal tumors were unilateral, located in the right kidney in 15 cases. It revealed the presence of inferior vena cava (IVC) thrombosis in 7 patients, pulmonary metastases in 8 patients, hepatic metastases in 5 patients, and bone metastases in 2 patients. Histological diagnosis was established via renal biopsy in 7 patients.

Therapeutic management included preoperative chemotherapy in 25 patients, resulting in tumor reduction in 18 patients (72%), complete resolution of pulmonary metastases in 4 patients, and partial reduction in 3 patients. Surgery consisted of extended total uretero-nephrectomy in 26 patients and partial nephrectomy in 3 patients. Four patients underwent immediate surgery: two due to compressive symptoms requiring urgent intervention, and two others for cystic lesions not warranting preoperative chemotherapy. Three of the four operated patients received postoperative chemotherapy.

Histological analysis revealed 23 cases of nephroblastoma (blastemal in 10, regressive in 8, epithelial in 1, mesenchymal in 1, mixed in 2, and completely necrotic in 1), four cases of renal cell carcinoma (clear cell in 2, papillary in 1, and MiTF translocation-associated carcinoma in 1), and two cases of clear cell sarcoma of the kidney.

Staging of nephroblastomas was performed according to the SIOP classification. Most patients had locally advanced disease: 1 case at stage I, 2 cases at stage II, 20 cases at stage III, and 8 cases at stage IV. No patients were classified as stage V.

Postoperative chemotherapy was selected based on stage and histological type. Seventeen patients received high-risk chemotherapy, and 8 received intermediate-risk chemotherapy. Patients with renal cell carcinoma did not receive postoperative chemotherapy. Nineteen out of 25 patients were irradiated (76%): 18 cases of locally advanced nephroblastoma (stage III per SIOP classification) were irradiated to the renal bed with total doses ranging from 10.5 Gy to 25.2 Gy (median: 15.2 Gy). Two patients with pulmonary metastases received lung irradiation at a dose of 12 Gy.

The histological types of irradiated nephroblastomas were: blastemal in 9 cases, regressive in 8 cases, and mesenchymal in 1 case.

Regarding renal sarcomas, one patient received postoperative irradiation to the renal bed at a dose of 25.2 Gy, while the second could not be irradiated due to rapid disease progression.

During follow-up, complete remission was achieved in 16 of the 23 nephroblastoma cases (69%). Seven deaths were recorded: five patients experienced pulmonary relapse, were treated with high-risk chemotherapy, but showed progression of pulmonary metastases and died from respiratory distress. Two other patients discontinued treatment during postoperative chemotherapy and died due to tumor progression.

Both cases of renal sarcoma relapsed and subsequently died, while all four cases of renal carcinoma are alive in remission.

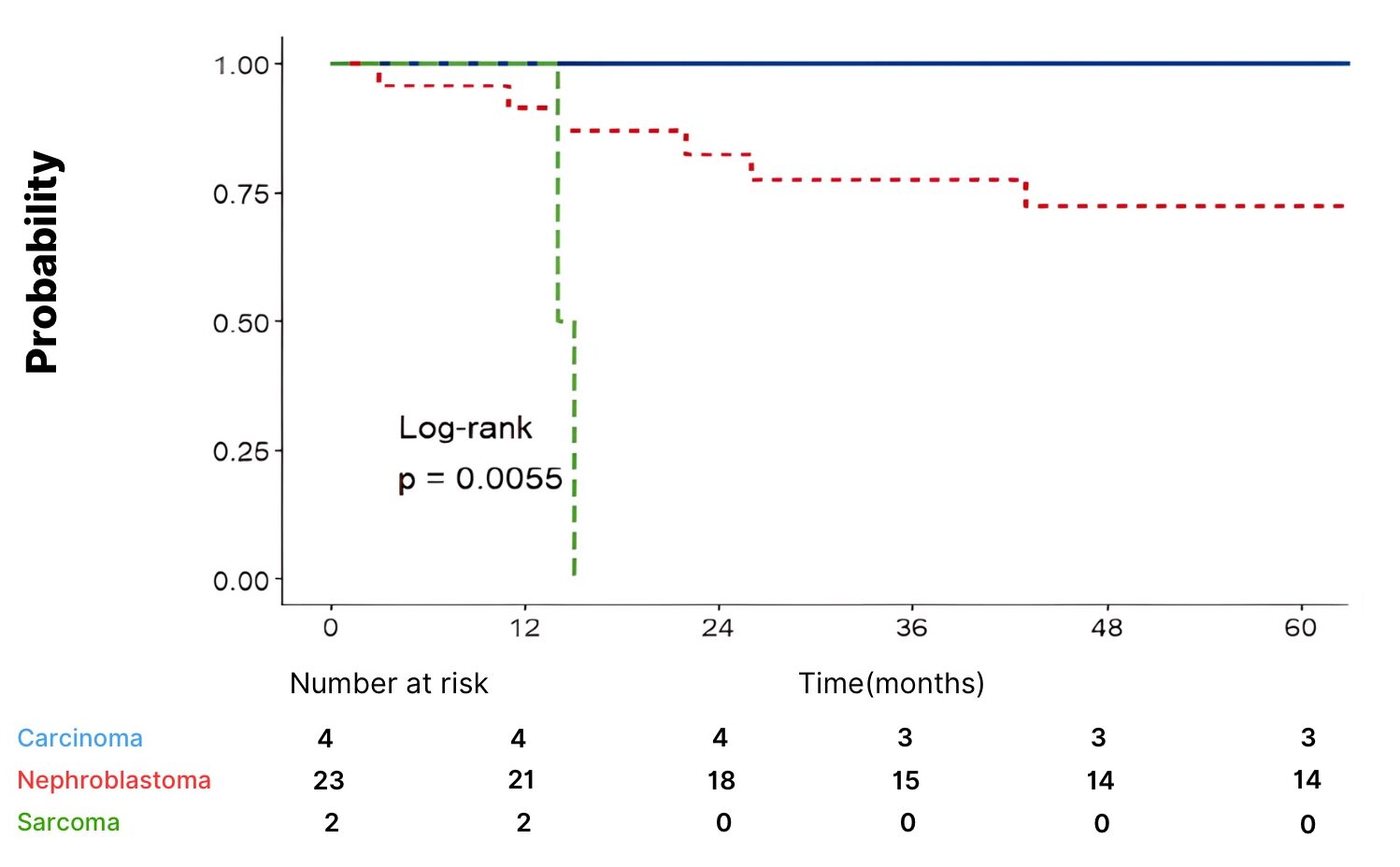

Survival analysis showed an overall survival rate of 92.8% at 1 year, 73.5% at 3 years, and 68.6% at 5 years. Event-free survival in our cohort was 79% at 1 year, and 68% at both 3 and 5 years.

Survival by histological type revealed a 100% 5-year survival for clear cell carcinoma cases, and for nephroblastoma cases: 93.1% at 1 year, 87% at 3 years, and 77.5% at 5 years. (Figure 1)

Fig. 1 Survival Curve According to Histological Diagnosis

Multivariate analysis using the Cox regression model revealed that the sarcomatous histological type (HR = 287.8, p<0.001) was significantly associated with an increased risk of relapse. The regressive type showed a trend toward an increased risk (p = 0.066), but did not reach statistical significance.

The presence of metastases increased the risk of relapse, though not significantly (p=0.184), possibly due to the low number of events.

The SIOP stage did not appear predictive in this model, likely due to the sample being heavily dominated by stage III, limiting the power of comparison.

Age was not statistically significant (p=0.145), but the trend suggested that younger children may have a slightly higher risk of relapse.

Figure 2: Overall Flowchart of Patient Outcomes in Our Cohort

Discussion

Renal tumors account for between 3.2% and 11.1% of pediatric cancers worldwide, with notable ethnic variations. Wilms tumor (nephroblastoma) represents over 90% of renal tumors in children aged 1 to 7 years and remains predominant even in older children, followed by renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and clear cell sarcoma of the kidney (CCSK)3. From age 10, the incidence of RCC increases, becoming equivalent to that of Wilms tumor, and after age 12, RCC accounts for more than 50% of malignant renal tumors4,5. A study conducted in the UK between 1950 and 2017 found that among children over 5 years old, 75% of tumors were Wilms tumors, 10.7% RCC, and 0.9% CCSK6. In our study, these proportions were 79.2%, 13.8%, and 7%, respectively.

The median age at diagnosis of Wilms tumor is between 36 and 40 months, with a peak at 3.5 years. Approximately 10% of cases occur after age 77,8. A UK study reported a median age of 6 years in patients over 5 years old2, while in our series, the age ranged from 7 to 15 years, with a median of 8 years.

RCC typically presents later than Wilms tumor, usually between ages 9 and 15, compared to a mean age of 3 years for Wilms tumor9,10. A study reported a mean age of 16.7 years for RCC patients, significantly higher than the 13.9 years for Wilms tumor patients11. In our study, the mean age was 8 years for Wilms tumor and 12 years for RCC.

For CCSK, the median age at presentation is similar to that of Wilms tumor, around 36 months, with frequent presentation between 18 and 54 months12,13. In our series, the median age for CCSK was 9 years.

The most typical presentation of Wilms tumor is an asymptomatic abdominal mass in a child in good general condition, reported in nearly all series with a frequency ranging from 57% to 95%. In contrast, up to 90% of RCC patients are symptomatic at diagnosis, most commonly presenting with abdominal pain (43%) or hematuria (37%). CCSK presents similarly to Wilms’ tumor. In our study, an abdominal mass was the presenting symptom in 72% of cases.

In our series, all renal tumors diagnosed in children aged 7 years and older were unilateral, with 15 cases located in the right kidney. Pulmonary metastases were observed in 8 cases (27%). A UK study in children over 5 years old found pulmonary metastases in 21% of cases and 16% of RCC cases at diagnosis, whereas in our series, 39% of Wilms tumor cases had pulmonary metastases at diagnosis, and none of the four RCC cases had pulmonary metastases2. For CCSK, in the study by El Kababri et al. at the pediatric hematology and oncology department in Rabat, 1 out of 13 CCSK cases had pulmonary metastases at diagnosis; in our study, 1 out of 2 CCSK patients had pulmonary metastases14.

Histopathological analysis confirmed Wilms tumor in 23 cases (79%), RCC in 4 cases (14%), and CCSK in 2 cases (7%), consistent with literature data.

In our series, the majority of patients (87%) had stage 3 tumors, followed by 9% at stage 2 and 4% at stage 1. In the study by Popov et al., in children aged 10 to 16, 30% were stage 1, 26% stage 4, 24% stage 3, and 18% stage 26. In the study by Mansfield et al., in children over 5 years old, 31.7% were stage 4, 25.3% stage 3, 21.5% stage 1, and 17.7% stage 3I2.

According to the SIOP 2001 classification, our patients were categorized as high-risk in 56.5% of cases, intermediate-risk in 39.15%, and low-risk in 4.35%.

The treatment of pediatric renal tumors is multidisciplinary, involving varying combinations of chemotherapy, surgery, and radiotherapy. Cure rates have significantly improved, rising from 20% to 90% over the past four decades.

Two approaches exist for the initial management of pediatric renal tumors. COG protocols recommend upfront nephrectomy to obtain a precise histological diagnosis before initiating postoperative chemotherapy. In contrast, the SIOP-RTSG (Renal Tumor Study Group) protocols favor preoperative chemotherapy to reduce the risk of tumor rupture, achieve more favorable staging, and incorporate histological response into postoperative risk stratification. Over the past 15 years, collaboration between SIOP-RTSG and COG has led to data sharing and the development of the UMBRELLA guidelines, launched in June 2019, for diagnosis and treatment. Histopathological analysis of the resected specimen confirms the diagnosis, determines the stage, and guides postoperative treatment, which may include chemotherapy and, when indicated, radiotherapy15,16,17,18.

For Wilms’ tumor, the survival rate reaches approximately 95%. In our series, the 5-year survival rate was 77.5%, compared to 63% in the study of Popov et al.17 . Mansfield et al. found no significant survival difference by age, consistent with our findings2. They also reported 19 relapses among 84 cases (22.6%)2 comparable to the 5 relapses among 23 patients (22%) in our series. Popov et al. reported 16 deaths (32%)6, while we recorded 7 deaths (24%).

For RCC, Popov et al. reported a 40% survival rate (4/10), including 3 papillary carcinomas and 1 unclassified12. Broecker et al. observed a 67% survival rate (4/6)19. In our series, all four patients remain alive in continuous complete remission, corresponding to a 5-year survival rate of 100%.

For CCSK, the SIOP study (1987–1991) reported a 5-year overall survival of 88% among 28 patients treated with a four-drug chemotherapy regimen including doxorubicin20. In our series, both CCSK cases resulted in death.

In our series, the SIOP stage did not show significant prognostic value. In the combined analysis of SIOP 93-01 and SIOP 2001 studies, stage 3 patients had a higher risk of relapse compared to stage 1, but this difference lost statistical significance after adjusting for 1q gain or stratifying by relapse site in the SIOP 2001 cohort21,22.

The presence of metastases at diagnosis increased the risk of relapse in our series, though not significantly. Currently, the response of metastatic disease to chemotherapy is considered a more relevant prognostic indicator than the mere presence of metastases. This has been demonstrated in stage 4 patients with isolated pulmonary metastases, where rapid and complete responders have significantly better outcomes than slow or incomplete responder21,23.

Furthermore, Weirich et al. reported that completely necrotic, stromal, or epithelial Wilms tumors were associated with better prognosis than regressive, mixed, or blastemal types21,24, consistent with our observations.

Numerous prognostic risk factors have been identified in the literature: older age, advanced tumor stage, lymph node involvement, unfavorable histology, residual tumor, relapse, and certain molecular markers, particularly 1q gain and tumor volume >500 mL, have all been associated with poorer prognosis21,25.

Conclusion

Wilms’ tumor remains the most common renal malignancy in children, including those over the age of 7. However, the significant proportion of non-Wilms tumors highlights the histological heterogeneity of these neoplasms and the complexity of their management. These non-Wilms forms, often diagnosed at an advanced stage and associated with a less favorable therapeutic response, confirm their overall poorer prognosis compared to classic Wilms tumor.

Early diagnosis, precise histological characterization, access to appropriate surgery, chemotherapy based on standardized protocols such as GFA Nephro 2005, and radiotherapy when indicated, constitute the pillars of effective multimodal treatment. These elements align with international recommendations, particularly those of the World Health Organization, which advocates for early detection and equitable access to optimized treatments for pediatric cancers.

In the Moroccan context, and more broadly in resource-limited countries, strengthening diagnostic capabilities, disseminating validated therapeutic protocols, and ensuring continuous training of multidisciplinary teams are top priorities. Improving infrastructure, ensuring access to essential medications, and networking specialized centers will help reduce disparities in access to care and improve survival rates among children with malignant renal tumors.

Cell resting for 18–24 hours is essential for accurate quantification of virus-specific T-lymphocytes in CD45RA-depleted donor products. Long-term cryopreservation significantly reduces VST functionality, although partial restoration is possible. ELISpot analysis is recommended prior to clinical use of thawed products.

Competing Interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

License

© The Author(s) 2025.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, and unrestricted adaptation and reuse, including for commercial purposes, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

References

-

Brok J, Treger TD, Gooskens SL, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Pritchard-Jones K. Biology and treatment of renal tumours in childhood. Eur J Cancer. 2016 Nov;68:179-95.

-

Mansfield SA, Lamb MG, Stanek JR, et al. Renal tumors in children and young adults older than 5 years of age. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2020 May;42(4):287–91.

-

Koh KN, Han JW, Choi HS, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical outcomes of pediatric renal tumors in Korea: A retrospective analysis of the Korean Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Group (KPHOG) data. Cancer Res Treat. 2023 Jan;55(1):279–90.

-

Nakata K, Colombet M, Stiller CA, et al. Incidence of childhood renal tumours: An international population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2020 Dec 15;147(12):3313–27.

-

Qureshi SS, Bhagat M, Verma K, et al. Incidence, treatment, and outcomes of primary and recurrent non-Wilms renal tumors in children: Report of 109 patients treated at a single institution. J Pediatr Urol. 2020 Aug;16(4):475.e1–9.

-

Popov SD, Sebire NJ, Pritchard-Jones K, Vujanić GM. Renal tumors in children aged 10–16 years: a report from the United Kingdom Children’s Cancer and Leukaemia Group. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2011 May–Jun;14(3):189–93.

-

Collins A, Demarche M, Dresse MF, et al. Les tumeurs rénales de l’enfant. Une étude mono‑centrique: à propos de 31 cas. Rev Med Liege. 2009;64(11):552–59. Available from: https://rmlg.uliege.be/article/1947

-

Hajbi A. Néphroblastome compliqué d’un thrombus de la veine cave inférieure et de l’oreillette droite [Thèse de doctorat en médecine]. Rabat: Université Mohammed V; 2018. Available from: https://toubkal.imist.ma/handle/123456789/28706

-

Helmy T, Sarhan O, Sarhan M, et al. Renal cell carcinoma in children: single-center experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2009 Sep;44(9):1750–3.

-

Asanuma H, Nakai H, Takeda M, et al. Renal cell carcinoma in children: experience at a single institution in Japan. J Urol. 1999;162(4):1402–5.

-

Grabowski J, Silberstein J, Saltzstein SL, et al. Renal tumors in the second decade of life: results from the California Cancer Registry. J Pediatr Surg. 2009 Jun;44(6):1148-51.

-

Gooskens SL, Furtwängler R, Vujanic GM, et al. Clear cell sarcoma of the kidney: A review. Eur J Cancer. 2012 Sep;48(14):2219–2226.

-

Aldera AP, Pillay K. Clear cell sarcoma of the kidney. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2020 Jan;144(1):119–123.

-

El Kababri M, Khattab M, El Khorassani M, et al. Sarcome rénal à cellules claires: A propos d’une série de 13 cas [Clear cell sarcoma of the kidney. A study of 13 cases]. Arch Pediatr. 2004 Jul;11(7):794–799.

-

Vujanić GM, Gessler M, Ooms AHAG, et al. The UMBRELLA SIOP-RTSG 2016 Wilms tumour pathology and molecular biology protocol. Nat Rev Urol. 2018 Nov;15(11):693–701.

-

van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Hol JA, Pritchard-Jones K, et al. Position paper: Rationale for the treatment of Wilms tumour in the UMBRELLA SIOP-RTSG 2016 protocol. Nat Rev Urol. 2017 Dec;14(12):743–752.

-

Gooskens S, Graf N, Furtwängler R, et al. Rationale for the treatment of children with CCSK in the UMBRELLA SIOP-RTSG 2016 protocol. Nat Rev Urol. 2018;15:309–319.

-

Cunningham ME, Klug TD, Nuchtern JG, et al. Global disparities in Wilms tumor. J Surg Res. 2020 Mar;247:34–51.

-

Broecker B. Renal cell carcinoma in children. Urology. 1991 Jul;38(1):54–56.

-

Furtwängler R, Gooskens SL, van Tinteren H, et al. Clear cell sarcomas of the kidney registered on International Society of Pediatric Oncology (SIOP) 93-01 and SIOP 2001 protocols: A report of the SIOP Renal Tumour Study Group. Eur J Cancer. 2013 Nov;49(16):3497–3506.

-

Groenendijk A, Spreafico F, de Krijger RR, et al. Prognostic factors for Wilms tumor recurrence: A review of the literature. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Jun 23;13(13):3142.

-

Hol JA, Lopez-Yurda MI, Van Tinteren H, et al. Prognostic significance of age in 5631 patients with Wilms tumour prospectively registered in International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) 93-01 and 2001. PLoS One. 2019 Aug 19;14(8):e0221373.

-

Verschuur A, Van Tinteren H, Graf N, et al. Treatment of pulmonary metastases in children with stage IV nephroblastoma with risk-based use of pulmonary radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Oct 1;30(28):3533–3539.

-

Weirich A, Ludwig R, Graf N, et al. Survival in nephroblastoma treated according to the trial and study SIOP-9/GPOH with respect to relapse and morbidity. Ann Oncol. 2004 May;15(5):808–820.

-

Bordbar S, Shahriari M, Zekavat OR, et al. The outcomes of children with primary malignant renal tumors: A 14-year single-center experience. BMC Cancer. 2024 Nov 12;24(1):1388.