Treatment Outcome of Childhood Hepatoblastoma: A Single Centre Experience in Bangladesh

Abstract

Background: Hepatoblastoma is a rare malignant liver tumor that occurs almost exclusively in childhood. Although surgical resection is the foundation of curative therapy in hepatoblastoma, with the use of effective neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy, the survival of patients with hepatoblastoma has improved significantly.

Objective: To evaluate the clinical characteristics and treatment outcome of childhood hepatoblastoma treated at a tertiary care center in Bangladesh.

Methods: This observational study was conducted in the Department of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, Bangladesh. The patient’s data were analyzed for clinical characteristics, treatment modalities, and survival outcomes.

Result: Twenty-four patients who were treated for Hepatoblastoma at our center were included in the study. Sixteen (66.5%) of them were male and M:F = 3:1 . The median age of presentation was 2.8 years, and 62.5% of patients were below 3 years of age. The median time of diagnosis after onset of symptoms was 8 months. An abdominal mass (90%) and abdominal pain (59.8%) were the most common presenting symptoms. The serum alpha-fetoprotein at the time of initial evaluation was raised in 96% of patients. The fetal histology (62.5%%) was the most common histological subtype. Two (8.4%), 7 (29 %), 8 (33.6%), and 7 (29 %) patients were found to have pre-treatment extent of tumor (PRETEXT) stages I, II, III, and IV, respectively. Seventeen (71 %) children were classified as standard risk, and 7 (29%) children as high risk. Complete resection of the primary tumor was possible in 11 (46%) patients. Out of the studied patients 12.5% developed relapse. Five-year overall survival was 66.6% and event-free survival was 58.3%.

Conclusion: The treatment outcome of hepatoblastoma at our center is comparable to other countries. The feasibility of all modalities of treatment, like liver transplantation in children, may improve the outcome.

Introduction

Approximately two-thirds of hepatic tumors occurring in children are malignant. Hepatoblastoma and hepatocellular carcinoma constitute the two most common primary hepatic malignancies in children. Hepatoblastoma is the most common liver cancer in children, representing approximately 1% of all pediatric malignancies, and is usually diagnosed during the first 3 years of life1. Complete tumor resection is the cornerstone of therapy for liver tumors and offers the only realistic chance of long-term disease-free survival2,3. The introduction of effective chemotherapeutic regimens for the treatment of hepatoblastoma has significantly improved the survival of children with this tumor by increasing the number of patients who can ultimately undergo tumor resection and by reducing the incidence of post-surgical recurrences. Cures hepatoblastoma requires gross tumor resection. If hepatoblastoma is completely removed, the majority of patients survive, but less than one-third of patients have lesions amenable to complete resection at diagnosis. Thus, it is critically important that a child with probable hepatoblastoma be evaluated by a pediatric surgeon experienced in the resection of hepatoblastoma in children. Chemotherapy can often decrease the size and extent of hepatoblastoma, allowing complete resection3,4,5.

Orthotopic liver transplantation provides an additional treatment option for patients whose tumor remains unresectable after preoperative chemotherapy6,7. Although the cure rates for childhood hepatoblastoma are high in developed countries, the success is poor in resource-limited countries. In these countries, however, the unavailability of some active drugs, inadequate supportive care, life-threatening toxicities of modern chemotherapy, a lack of liver transplant facility, and low protocol compliance by patients or physicians may significantly reduce patient outcome.

Data from Bangladesh about the management of hepatoblastoma is limited8. There is a paucity of published information from Bangladesh on children with hepatoblastoma. This study aims to assess current treatment outcomes of children with hepatoblastoma in our country. The present study was performed to analyze the clinical characteristics, treatment, and survival outcomes of hepatoblastoma patients who received treatment at our center and to describe a management pattern of hepatoblastoma in a resource-limited setting.

Methodology

This observational study was conducted for a period of 3 years, from January 2012 to December 2014, in the Department of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, Bangladesh, and a 5-year follow-up was done. Patient’s data were analyzed for the clinical characteristics, modalities of treatment, and survival outcome of the included patients. Patients enrolled in this study were grouped as standard risk and high risk and treated accordingly. The institutional ethics committee approved this study. Informed written consent was taken from parents.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of hepatoblastoma was based on clinical features and elevated serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels. All the patients underwent contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of chest, abdomen, and pelvis, and PRETEXT (Pre-Treatment Extent) stage was assigned based on the CT findings3. Treatment decisions were taken by a multi-disciplinary team. High-risk (HR) was defined as a tumor in all liver sections (PRETEXT-IV), or vascular invasion (portal vein [Pþ], three hepatic veins [Vþ]), or intra-abdominal extrahepatic extension (Eþ), or metastatic disease, or alpha-fetoprotein less than 100 ng/ml at diagnosis. Biopsy of the primary tumor was mandatory in children younger than 6 months of age because of the wide differential diagnosis of hepatic masses and the possible confounding effect of an elevated serum AFP at this age and older than 3 years, because of the risk of misdiagnosing hepatocellular carcinoma or with normal serum AFP9.

Biopsy was not mandatory in children between 6 months and 3 years of age with clinical findings strongly favoring the diagnosis of hepatoblastoma (radiological evidence of an intrahepatic mass, elevated serum AFP, thrombocytosis), but histopathological examination was only strongly recommended after tumor resection10.

Out of 24 patients, 22 received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) followed by surgery. Serum AFP levels were monitored before each cycle, and imaging was usually done after 4 to 7 cycles of chemotherapy. Those who had inoperable diseases on reassessment were given 2 more cycles of chemotherapy and reassessed. The timing of surgery was individualized and was decided by the surgical team. After surgery, adjuvant chemotherapy was delivered to complete a total of 6 to 10 cycles. For all pediatric patients with PRETEXT I, II, III, or IV, neoadjuvant chemotherapy was applied first, usually with 3 -7 cycles of chemotherapy before the operation and 3 – 4 cycles of consolidation chemotherapy after the operation. The conventional first-line chemotherapy protocol comprised cisplatin + fluorouracil + vincristine (C5V -COG protocol), cisplatin+ Doxorubicin (PLADO protocol), and cisplatin+ Doxorubicin+Carboplatin (SuperPLADO) regimen (SIOPEL protocol). Ten patients were treated according to the COG regimen, and 14 patients were treated with the SIOPEL regimen.

Doxorubicin and cisplatin (PLADO) were the most used chemotherapy regimen; some patients received COG (5 FVC) and high-risk patients were treated with superPLADO. PLADO chemotherapy consisted of cisplatin on day 1 at a dose of 80 mg/m2, administered in a continuous 24-h infusion and doxorubicin at a dose of 30 mg/m2 per day, administered as a continuous 24-h intravenous infusion on days 2 and 3. In each 5FVC regimen, patients were treated with cisplatin (100 mg /m2 IV infused over 6 hours, day 1), vincristine (1.5 mg / m2, max 2 mg IV flush on day 3,10, 17), and 5 – 5-fluorouracil (600mg/m2 IV push, day 3) at every 3 – 4 weeks interval.

During follow-up, serial AFP levels were done every 3 months for the first 3 years and every 6 months for the next 2 years. Ultrasound imaging of the abdomen was performed every 6 months for the first 3 years of follow-up.

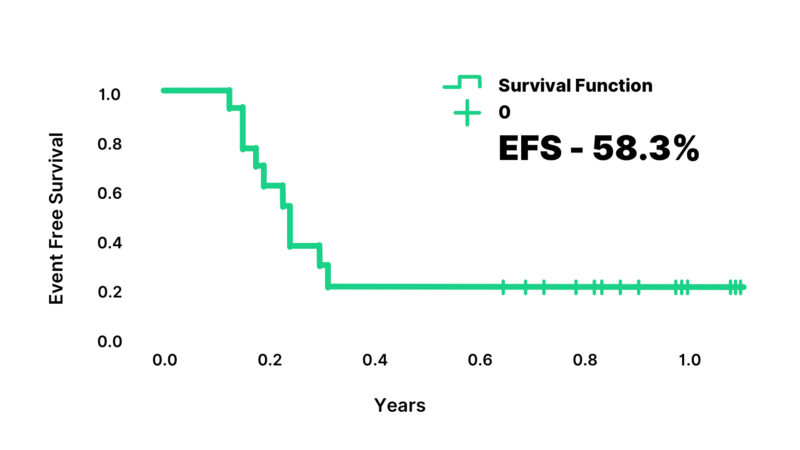

An event was defined as death due to any cause or relapse, or progression of disease. Patients were censored on the date of last follow-up. Event-free survival (EFS) was calculated from the date of initiation of treatment to the date of relapse or progression, or death.

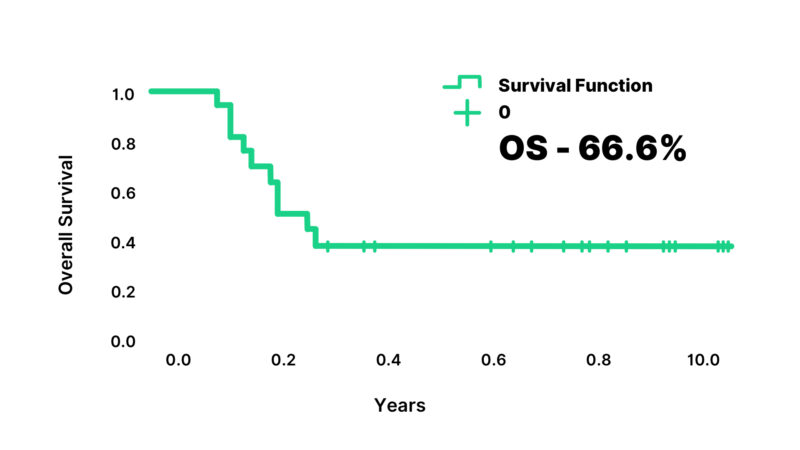

The follow-up period was up to December 2020, and the follow-up was completed by returning to the hospital for re-examination and telephone follow-up. According to the results of the follow-up, the clinical data, overall survival (OS), and event-free survival (EFS) of the children were analyzed. EFS and Overall survival (OS) were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 20.0. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Response evaluation was done by serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level, which was estimated before each cycle of chemotherapy, and by using RECIST criteria (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumor)11. Imaging examinations (both ultrasonography, CT) of the primary and/or metastatic lesions were performed after every two cycles of chemotherapy. Therapeutic effect was defined as complete remission (CR) is the tumor had disappeared completely after the treatment, and there was no evidence of residual tumor in the imaging, together with the serum AFP being normal for more than 4 weeks. Partial remission (PR) is the tumor size had decreased by more than 50%, without new focus, and the serum AFP had decreased significantly. Progressed disease (PD) is the tumor volume having increased by more than 25%, with a new tumor focus, or the AFP had increased or exceeded the normal value for two consecutive weeks during the treatment. Recurrence is after complete remission. It was confirmed by pathological biopsy that the tumor had appeared again, or there was clear imaging evidence, and the serum AFP had increased three times within 4 weeks, or death.

Results

During the study period, 24 patients diagnosed with hepatoblastoma received treatment at our Institute. Sixteen (66.7%) of them were male, and Male: Female was = 3:1. The median age of presentation was 2.8 years (range 2 months to 10 years), and 62.5% patients were below 3 years of age. The median time of diagnosis after onset of symptoms was 8 months. An abdominal mass (90%) and abdominal pain (59.8%) were the most common presenting symptoms. The demographic characteristics of patients are listed in Table 1.

Table 1 : Demographic Characteristics of the Patients

| Characteristics | Patients | |

|---|---|---|

| No. | % | |

| Age (Years) | ||

| Median | 2.8 | |

| Range | 2 Months - 10 Years | |

| < 3 | 15 | 62.5 |

| ≥ 3 | 9 | 37.5 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 16 | 66.7 |

| Female | 8 | 33.3 |

| AFP, ng/ml | ||

| Median | 1283.5 | |

| Range | 1.81 | 58344 |

| < 100 | 5 | 20.8 |

| PRETEXT Staging | ||

| Stage I | 2 | 8.4 |

| Stage II | 7 | 29.1 |

| Stage III | 8 | 33.4 |

| Stage IV | 7 | 29.1 |

| Presence of Distant Metastasis | 6 | 25 |

| Tumor rupture at diagnosis | 0 | 0 |

| Histological Subtypes | ||

| Fetal | 15 | 62.5 |

| Embryonal | 2 | 8.3 |

| Mixed | 1 | 4.2 |

| Anaplastic | 6 | 25 |

| Risk group | ||

| Standard Risk | 17 | 70.9 |

| High Risk | 7 | 29.1 |

| Preoperative Chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 22 | 91.6 |

| No | 2 | 8.4 |

| Surgery | ||

| Hepatectomy | 16 | 66.6 |

| Liver Transplantation | 0 | 0 |

| No Surgery | 8 | 33.4 |

Three (12.5%) have a history of cancer in their family. Two patients had a history of low birth weight, one had a history of maternal use of hormonal therapy, and none of the patients had documented congenital anomalies.

Median platelet count was 522 (± 223.91) x 109/L with a range of 206 to 900 x 109/L. The majority of the patients (66.6%) had thrombocytosis, that is, platelet count > 450×109/L. The serum alpha-fetoprotein at the time of initial evaluation raised 96% of patients.

The fetal histology (62.5%) was the most common histological subtype. Two (8.3%), 7 (29.1%), 8 (33.3%), and 7 (29.1%) patients were found to have pre-treatment extent of tumor (PRETEXT) stages I, II, III, and IV, respectively. Seventeen (70.9%) children were classified as standard risk and 7 (29.1%) children as high risk. Among them, 6 patients had metastatic disease at presentation, 2 had portal vein involvement. All the patients had normal liver function tests at the time of presentation. Twenty-two of 24 patients (91.6%) received NACT, and 2 (8.4%) underwent upfront surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy. Ten patients received the 5FCV protocol and 14 patients received PLADO and superPLADO protocol of chemotherapy.

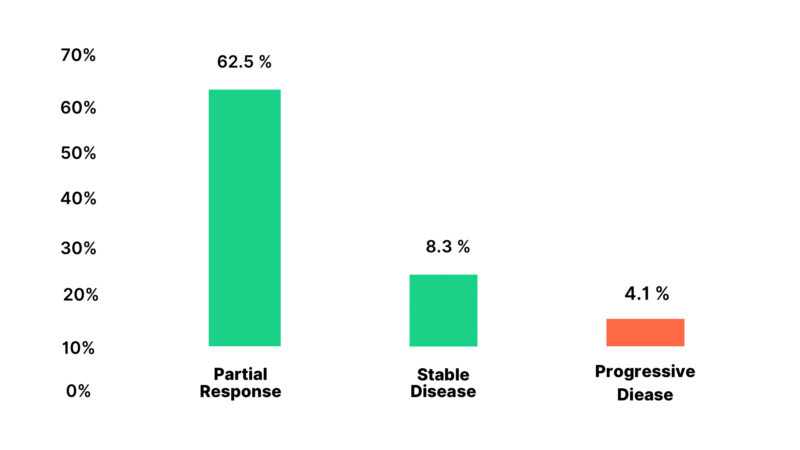

Out of 22 patients who received NACT 14 (63.6%) had a partial response, 5 (22.8%) had stable disease, and 3 (13.6%) had disease progression Figure 1.

Figure 1: Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy of the Patients

Complete surgical resection of the primary tumor was possible in 11 (46%) patients; those who had progressive disease were on only chemotherapy and did not undergo surgery, and 2 of them died while receiving chemotherapy. The patient who had stable disease 3 out of 5 undergone delayed surgery. Liver transplantation was a curative treatment option indicated for patients who had disease progression in the liver or unresectable or stable disease without distant metastasis, but there is no feasibility of liver transplantation in our country. Out of the patients studied, 3 (12.5%) developed relapses.

Vomiting was the most common toxicity of hepatoblastoma treatment in the patients. Grade 3 or 4 anemia and thrombocytopenia, and Grade 4 neutropenia were observed in 62%, 27.80% and 38.5% respectively. Febrile neutropenia occurred in 85% and septicemia developed in 81.4%. Red cell concentrations and platelet transfusions were required in 42.8% and 12% respectively. One patient developed cisplatin-induced autoimmune hemolytic anemia. This patient was managed with supportive treatment and had a complete recovery. Eight patients (33.3%) required reductions during the different cycles of treatment. There were 8 deaths in the study; 5 deaths were due to progressive disease, and 3 deaths were due to treatment-related toxicity and relapse. At a median follow-up of 92 months (range: 72 to 108 months), estimated 5-year overall survival was 66.6% and event-free survival was 58.3% (Figure 2,3).

Figure 2: Event-Free Survival of the patients

Figure 3: Overall Survival of the patients

Discussion

Hepatoblastoma is the most common liver tumor in pediatric patients. It mainly affects children between 6 months and 3 years age, and males are more affected than females. The management of hepatoblastoma has been possible with advanced treatment protocols that have been found in studies from multicenter trials. International Childhood Liver Tumor Strategy Group (SIOPEL) guidelines, that are widely used, suggest PRETEXT staging and the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy.

SIOPEL studies have shown that standard risk patients who treated with single agent cisplatin have similar outcomes to those treated with PLADO with decreased toxicity due to elimination of anthracycline. In high-risk patients intensified chemotherapy with SuperPLADO regimen had a better outcome7,9.

Children’s Oncology Group (COG) in North America recommends upfront surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy2. Outcomes from COG and SIOPEL studies have been comparable.

At our center COG chemotherapy regimen was used for some patients irrespective of their risk group, however, later PLADO and SuperPLADO protocol are used according to risk stratification. Ten patients were treated with the COG protocol and 14 patients received PLADO and superPLADO regimen of chemotherapy according to the SIOPEL protocol.

The median age of presentation in our study was 2.8 years, but in other studies, it has been reported that 14 months and 1.4 years in Asian countries12,13.

In our study, 2 patients had a history of low birth weight, very low birth weight is strongly associated with hepatoblastoma described in several studies14. But in our study, the history of low birth weight in studied patients was less, as most of the patients were delivered by NVD at home and birth weight measurement was not possible.

Most of the patients in our study had PRETEXT stage II or III disease, and this is similar to the distribution reported in SIOPEL-1 study3. In another study shown that PRETEXT I 3%, PRETEXT II 27%, PRETEXT III 44%, PRETEXT IV 26%, Lung metastases 63%, Vascular invasion 39% and abdominal extrahepatic disease (10%)15. In this study, 70.9% of children were classified as standard risk and 29.1% of children as high risk. Among them, 6 patients had metastatic disease at presentation, and 2 had portal vein involvement.

In the current study, histopathological examination of the tumor shows the fetal histology (62.5%) was the most common histological subtype, one study showed that only 5% patients had fetal type, another study found 41 % epithelial type, 56% mixed type, and 3% anaplastic type16,17.

Complete surgical resection was possible in 46% patients after NACT which was much lower in our study compared to studies found in India 65% (out of 27 patients), and China 80% (total no of patients was 60 )18,19.

One study showed that patients with HB were treated with seven courses of cisplatin, 5- 5-fluorouracil, and vincristine (C5V) for 7 cycles on the POG study. These patients exhibited a 75% resection rate4. Another study in the SIOPEL-2 study risk-adapted treatment with Cisplatin/Carboplatin/Doxorubicin showed that resection rates were 97% including several children undergoing liver transplantation10.

Five patients had stable diseases, and 3 had disease progression during the neoadjuvant chemotherapy period. In India, 63% of patients could undergo resection, and 20% required liver transplantation out of 30 patients20. But in our country, there is a lack of feasibility of liver transplantation in children. Around 20% of our patients had progressive disease, which is like other reports from India. Liver transplantation as a curative modality could not be performed in our patients in whom it was indicated. The major reason for not performing liver transplantation is the lack of expertise and support at our center.

There were two treatment-related deaths during neoadjuvant treatment (8%) in this study, which is much lower compared to other Indian studies (17.3%)13.

In our study, we found a 5-year OS was 66.6% and EFS was 58.3%, other Indian studies have reported survival ranging from 33 to 100% and one single center showed OS 67.9% and 5-year survival OS rates were 78.9%. In China study done on 316 children in China12,13. One study done in our institute previously from 2004 to 2012 found 5-year EFS and OS of 13 patients was 76.9%8.

To compare the treatment regimens, the patients were randomized to receive 8 cycles of either cisplatin and continuous infusion doxorubicin or C5V. EFS at 5 years for all patients was not significantly different between the two regimens2. Progressive disease occurred significantly less often in patients treated with cisplatin/doxorubicin (23%) versus those receiving C5V (39%). However, toxicity (including treatment-related mortality) was higher in the patient receiving cisplatin/doxorubicin, which led to similar 5-year EFS of 57% and 69% for patients receiving either C5V or cisplatin/doxorubicin, respectively. Since the OS between the two regimens on this trial were not different, but the toxicity of the two drug regimens (cisplatin and doxorubicin) was clearly more than the C5V regimen21.

In the current study, the toxicity profiles for the two chemotherapy regimens were similar except those patients in the SIOPEL experienced higher rates of febrile neutropenia and septicemia than the COG group. And the OS between the two regimens was also similar. During follow up we could not find any long-term toxicity related to treatment. The inferior outcome of childhood hepatoblastoma in resource-limited settings is mainly due to the lack of availability of liver transplantation facilities and treatment-related mortality.

Conclusion

The treatment outcome of childhood hepatoblastoma in resource-challenged settings is comparable to other Asian countries with combined modality treatment. Meticulously treating chemotherapy-related toxicity and establishing of liver transplantation facility and making it more affordable and accessible in our country will help in improving the outcomes further.

Competing Interests:

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Funding:

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Licence

© Author(s) 2025.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, and unrestricted adaptation and reuse, including for commercial purposes, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

References

-

Darbari A, Sabin KM, Shapiro CN, Schwarz KB. Epidemiology of primary hepatic malignancies in U.S. children. Hepatology. 2003;38(3):560-6.

-

Ortega JA, Douglass EC, Feusner JH, et al. Randomized comparison of cisplatin/vincristine/fluorouracil and cisplatin/continuous infusion doxorubicin for treatment of paediatric hepatoblastoma: a report from the Children’s Cancer Group and the Paediatric Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(14):2665-75.

-

Pritchard J, Brown J, Shafford E, et al. Cisplatin, doxorubicin, and delayed surgery for childhood hepatoblastoma: a successful approach—results of the first prospective study of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(22):3819-28.

-

Douglass EC, Reynolds M, Finegold M, Cantor AB, Glicksman A. Cisplatin, vincristine, and fluorouracil therapy for hepatoblastoma: a Pediatric Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(1):96-9.

-

Otte JB, Pritchard J, Aronson DC, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatoblastoma: results from the International Society of Pediatric Oncology (SIOP) study SIOPEL-1 and review of the world experience. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2004;42(1):74-83.

-

Czauderna P, Mackinlay G, Perilongo G, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in children: results of the first prospective study of the International Society of Pediatric Oncology group. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(12):2798-804.

-

Perilongo G, Maibach R, Shafford E, Brugieres L, Brock P, Morland B, et al. Cisplatin versus cisplatin plus doxorubicin for standard-risk hepatoblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(17):1662-70.

-

Rahman MA, Begum F, Karim S, Murtuza A, Islam A, et al. Multimodality treatment outcome of hepatoblastoma in a resource-limited country. Mymensingh Med J. 2017;26(2):272-8.

-

Zsíros J, Maibach R, Shafford E, Brugieres L, Brock P, Czauderna P, et al. Successful treatment of childhood high-risk hepatoblastoma with dose-intensive multiagent chemotherapy and surgery: final results of the SIOPEL-3HR study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15):2584-90.

-

Perilongo G, Shafford E, Maibach R, Aronson D, Brugieres L, Brock P, et al. Risk-adapted treatment for childhood hepatoblastoma: final report of the second study of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology SIOPEL 2. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40(3):411-21.

-

Eisenhauer EA, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228-47.

-

Dhali A, Mandal TS, Das S, et al. Clinical profile of hepatoblastoma: experience from a tertiary care centre in a resource-limited setting. Cureus. 2022;14(7):e26494.

-

Tian Z, Zhang WL, Zhang Y, Hu HM, Huang DS. Clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of hepatoblastoma in 316 children aged under 3 years: a 14-year retrospective single-center study. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21:170.

-

Ansell P, Michell CD, Roman E, Simpson J, Birch JM, Eden TOB. Relationship between perinatal and maternal characteristics and hepatoblastoma: a report from the UKCCS. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41(5):741-8.

-

Zsíros J, Brugieres L, Brock P, Roebuck D, Maibach R, Zimmermann A, et al. Dose-dense cisplatin-based chemotherapy and surgery for children with high-risk hepatoblastoma (SIOPEL-4): a prospective, single-arm, feasibility study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(9):834-40.

-

Malogolowkin MH, Howard M, Katzenstein H, Meyers ML, Krailo MD, Reynolds JM, et al. Complete surgical resection is curative for children with hepatoblastoma with pure fetal histology: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(24):3301-6.

-

Fuchs J, Rydzynski J, von Schweinitz D, Bode U, Hecker H, Weinel P, et al. Pretreatment prognostic factors and treatment results in children with hepatoblastoma: a report from the German Cooperative Pediatric Liver Tumor Study HB 94. Cancer. 2002;95(1):172-82.

-

Manuprasad A, Radhakrishnan V, Sunil B, et al. Hepatoblastoma: 16-years’ experience from a tertiary cancer centre in India. Pediatr Hematol Oncol J. 2018;3:13-6.

-

Liu APY, Ip JJK, Leung AWK, et al. Treatment outcome and pattern of failure in hepatoblastoma treated with a consensus protocol in Hong Kong. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66(1):e27482.

-

Shanmugam N, Scott JX, Kumar V, Vij M, Ramachandran P, Narasimhan G, et al. Multidisciplinary management of hepatoblastoma in children: experience from a developing country. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(3):e26249.

-

Black CT, Cangir A, Choroszy M, Andrassy J. Marked response to preoperative high-dose cisplatinum in children with unresectable hepatoblastoma. J Pediatr Surg. 1991;26(9):1070-3.