Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia in Children: A report from the Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Department in Rabat

Abstract

Background: Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL) is a rare subtype of acute myeloid leukemia. The introduction of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) has revolutionized APL treatment, transforming this once fatal leukemia into a highly curable disease. This study aims to report the experience of the hematology and oncology department of Rabat in the treatment of APL.

Methodology: This is a retrospective, analytical, and descriptive study of all patients under 15 years old diagnosed with APL and followed at the Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Department (PHOD) in Rabat between January 2012 and December 2022.

Results: During the study period, 12 children diagnosed with APL among 247 cases of AML were treated at PHOD in Rabat. The median age at diagnosis was 10.5 years, with a male predominance (sex ratio: 2). Three patients (25%) presented with a leukocyte count exceeding 10,000/mm³ at diagnosis. Four patients (33%) exhibited the hypogranular M3v variant. Eleven patients (92%) underwent induction chemotherapy combining cytarabine and daunorubicin, with eight receiving it combined with ATRA. Among them, three patients (37.5%) presented “Pseudotumor Cerebri” as a complication. Two patients (17%) died: one from leukostasis before treatment and the other from disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) during induction chemotherapy. Ten patients (75%) achieved complete remission (CR) following induction chemotherapy. Two of them did not receive ATRA and relapsed after the end of treatment.

Conclusion: The combination of arsenic and ATRA has transformed the prognosis of APL from one of the most severe to one of the most curable forms of leukemia. However, these treatments are not available in resource-limited countries. In Morocco, despite the availability of only ATRA, eight patients survived thanks to a better understanding of therapeutic adaptations and improved supportive care management.

Keywords: Acute promyelocytic leukemia, childhood, ATRA

Introduction

Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL), formerly designated as AML-M3 in the French-American-British (FAB) classification, accounts for 5 to 10% of all pediatric acute myeloblastic leukemias (AML)1. In children, this form of leukemia is less common but constitutes a therapeutic emergency due to the high risk of potentially fatal coagulopathies. APL is defined by a reciprocal, balanced, and recurrent translocation t(15, 17) (q22 q21), observed in 95 to 98% of cases. This translocation results in the formation of an oncogenic fusion gene (PML-RARα), which blocks cellular differentiation at the promyelocytic stage. Other genetic abnormalities involving the RARα gene may also be observed2.

Treatment of APL has undergone a dramatic transformation in recent years. The introduction of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) into chemotherapy protocols has led to excellent response and survival rates in adults. This approach was subsequently adopted in pediatric populations, yielding similarly outstanding outcomes3. Arsenic trioxide (ATO) was later incorporated into adult APL treatment, and its combination with ATRA enabled the development of entirely chemotherapy-free protocols. Thanks to these major therapeutic advances, APL-once associated with a grim prognosis, has become a highly curable disease. Long-term overall survival rates now exceed 90% in both pediatric and adult patients, including those with high-risk disease4.

Few studies have focused on APL in developing countries, due to its low incidence, the lack of reliable epidemiological registries, and the absence of structured research networks. Morocco was designated as a pilot site for the Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer (GICC), launched by the WHO in 2018, with particularly encouraging results. In this context, our study aims to analyze the epidemiological, clinical, biological, therapeutic, and outcome profiles of AML-M3 cases managed at the Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Department (PHOD) in Rabat, between January 2012 and December 2022.

Methodology

This is a retrospective, descriptive, and analytical study involving 12 patients diagnosed with acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), conducted over 11 years (January 2012 – December 2022). The study was carried out at the Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Department of the Children’s Hospital in Rabat. Data were collected from medical records and hospital registries at the Rabat Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Department, using a data collection sheet detailing the epidemiological, clinical, biological, prognostic, and therapeutic aspects of each child diagnosed with APL.

In Morocco, a national protocol (AML-MA-2011) for the management of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) was adopted in 2011 to treat all patients under 60 years of age, including children. The protocol includes an induction phase aimed at achieving complete remission (CR), followed by a second induction course and three consolidation courses, without maintenance therapy:

Induction 1

- Cytarabine 100 mg/m² every 12 hours from Day 1 to Day 10

- Daunorubicin 50 mg/m² on Days 2, 4, and 6

- Intrathecal (IT): Cytarabine (ARA), Methotrexate (MTX), Hydrocortisone (HC) (dose according to age) on Day

Induction 2

- Cytarabine 100 mg/m² every 12 hours from Day 1 to Day 10

- Daunorubicin 50 mg/m² on Days 1, 3, and 5

- Etoposide (VP16) 100 mg/m²/day from Day 1 to Day 5

- IT: ARA/MTX/HC on Day 1

Consolidation 1

- Cytarabine 3 g/m² every 12 hours from Day 1 to Day 3

- Daunorubicin 30 mg/m²/day on Days 3 and 4

- IT: ARA/MTX/HC on Day 1

Consolidation 2

- Cytarabine 3 g/m² every 12 hours from Day 1 to Day 3

- L-Asparaginase 6000 IU/m²/day on Day 4

- IT: ARA/MTX/HC on Day 1

Consolidation 3

- Cytarabine 1 g/m² every 12 hours from Day 1 to Day 3

- Daunorubicin 30 mg/m²/day from Day 1 to Day 3

- IT: ARA/MTX/HC on Day 1

In APL, the protocol includes all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) as a targeted therapy, administered from the beginning of induction and continued throughout chemotherapy, for a total duration ranging from 1 to 2 years.

Results

During the 11-year study period, the Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Department in Rabat managed 2,822 cancer cases, including 247 cases of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Twelve children were diagnosed with acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), representing 0.42% of all cancers and 4.86% of AML cases, with an average of one new case per year. The median age at diagnosis was 10.5 years (range: 2–16 years), with a male predominance (sex ratio: 2).

All patients in our cohort presented with hemorrhagic syndrome, including five cases associated with disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Anemic and infectious syndromes were observed in eight patients. The combination of all three syndromes was noted in six cases. The association of bone marrow failure syndrome and tumor syndrome-reflecting leukemic organ infiltration (hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy)-was identified in eight patients. No patient presented with isolated tumor syndrome. Three patients had hyperleukocytosis (>10,000/mm³), and four exhibited the hypogranular M3v variant.

Conventional karyotyping was performed in eleven patients, eight of whom showed the t(15;17) (q24;q21) translocation, confirming the diagnosis of APL. In four patients, the diagnosis was suspected based on evocative clinical and morphological features. All patients received transfusion support with packed red blood cells and platelets to maintain platelet counts above 50 G/L. Five children received fresh frozen plasma (FFP) transfusions due to DIC. Three patients were classified as high-risk and nine as standard-risk.

All patients were treated according to the national AML-MA-2011 protocol. Eleven received two induction courses based on cytarabine and daunorubicin, followed by three consolidation courses. In eight patients, ATRA was introduced at the start of the first induction and continued throughout the treatment. One patient diagnosed in December 2022 was treated according to the APL 2000 protocol, which included one induction course, two consolidation courses, and a 24-month maintenance therapy (weekly methotrexate, daily 6-mercaptopurine, and intermittent ATRA every 15 days for 3 months). Due to the unavailability of arsenic in Morocco, none of the patients received this treatment.

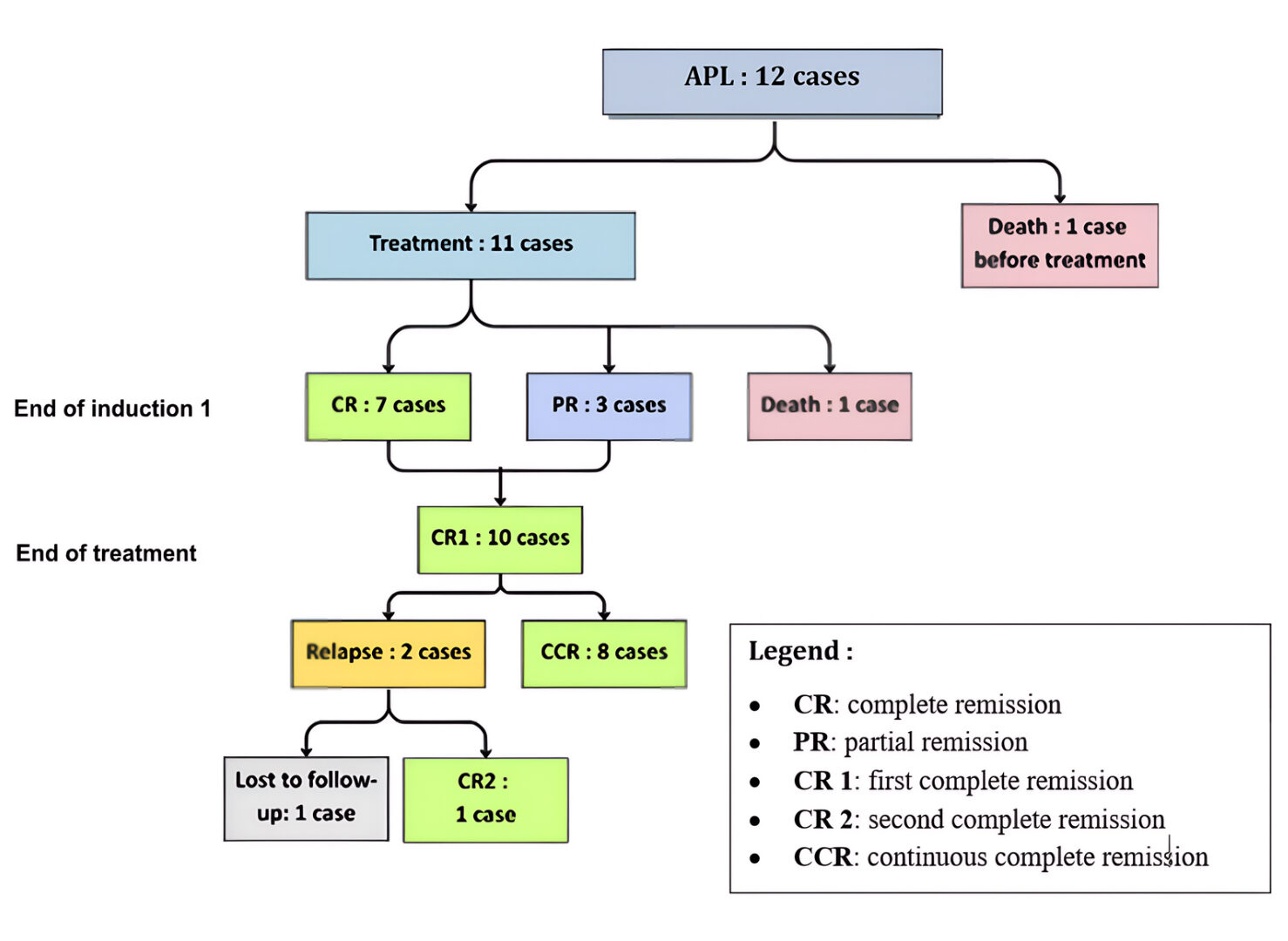

Among the eight patients treated with ATRA, three developed benign intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri) as a complication. Two patients who did not receive ATRA died: one due to leukostasis before treatment initiation, and the other from disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) during induction.

At the end of the first induction, seven patients achieved complete remission (CR), and three achieved partial remission (PR). Of these, two reached CR after the second induction, and the third after the second consolidation. Complete remission was achieved in ten patients by the end of treatment. Two patients who did not receive ATRA relapsed after 9 and 17 months, respectively. One was re-treated with the AML-MA-2011 protocol combined with ATRA and achieved a second CR, while the other was lost to follow-up.

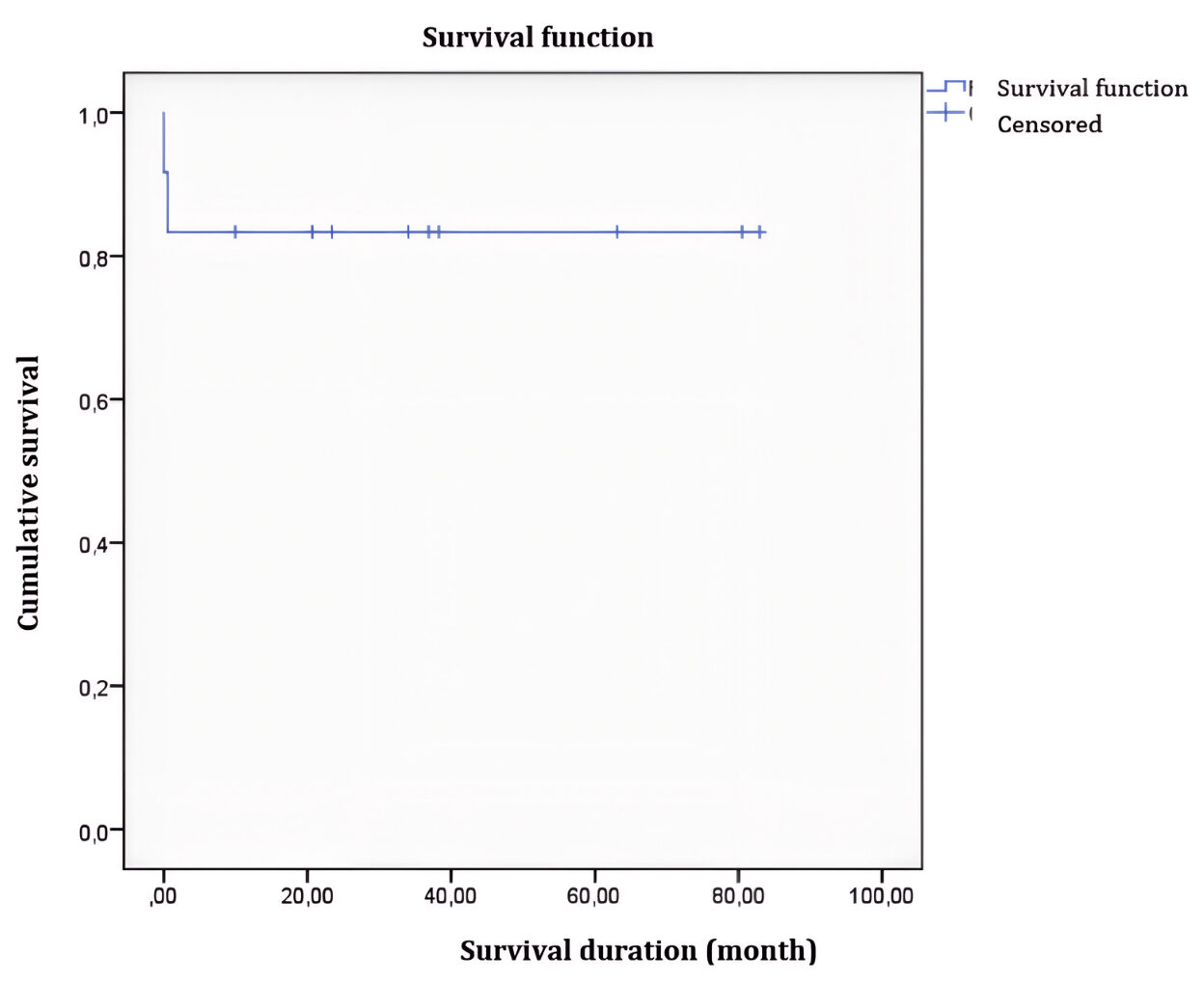

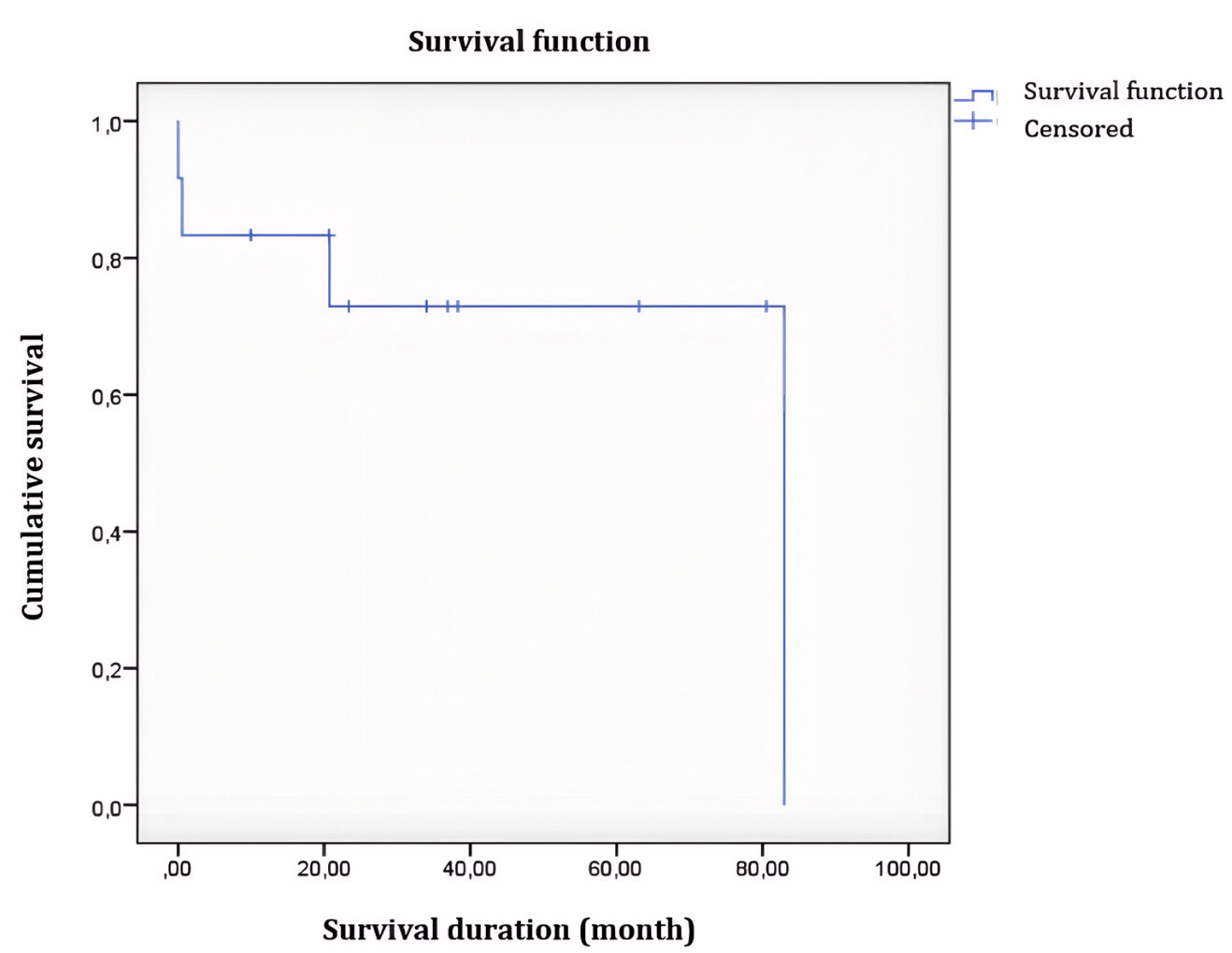

The 5-year overall survival (OS) rate was 83%, and the event-free survival (EFS) rate was 72%. For standard-risk patients, OS was 100%, and EFS was 86.6%, compared to 33.3% for both OS and EFS in high-risk patients.

Figure 1: Overall Survival Curve

Figure 2: Event-Free Survival Curve

Figure 3: Diagram showing the overall evolution of patients treated for APL

Discussion

The majority of pediatric leukemias are acute lymphoblastic leukemias (ALL), accounting for approximately 80% of cases, while acute myeloid leukemias (AML) represent a smaller proportion, estimated between 15% and 20%5. Although AML is relatively rare, its prognosis tends to be less favorable compared to other childhood cancers, often marked by a high relapse rate.

The first international classification of AML, the FAB classification, was based solely on cytological criteria and distinguished eight subtypes (AML M0 to M7). Advances in cytogenetic and molecular understanding of AML have enabled more precise patient stratification. Accordingly, the WHO classification of AML was revised in 2022 to emphasize the importance of genetic features6. However, in Morocco, access to cytogenetic testing remains limited. Karyotyping and molecular biology, which are essential for this classification, are not covered by the public health system and remain the financial responsibility of families, posing a major barrier to accurate diagnosis and optimal prognostic stratification.

APL is a subtype of AML, characterized by the t(15,17) (q24,q21) translocation, which leads to the formation of the PML-RARα fusion gene, a key element in its diagnosis. Pediatric incidence of APL varies across contexts. A multicenter retrospective study conducted in 16 centers in Korea reported a frequency of approximately 10% of de novo AML cases in children7, while in Brazil, a study of 931 AML cases over 17 years found an incidence of 17.5%8. In our cohort in Rabat, over eleven years, we recorded a lower incidence of 4.8%.

Despite the small sample size of 12 cases, our study shares similarities with other investigations in terms of median age. The median age at diagnosis in our patients was 10.5 years (range: 2–16 years), consistent with findings from other studies on pediatric APL7,8,9.

White blood cell count is the most significant prognostic factor in APL. Patients with counts ≥10,000/mm³ are considered high-risk for severe events, including mortality, which aligns with findings from several studies9,10. In our study, 25% of cases had white blood cell counts ≥10,000/mm³ at diagnosis, which is lower than the percentages reported in other pediatric APL studies (34.5%-48%)7,9,10,11.

The importance of karyotyping is well established in the diagnosis and management of AML according to WHO criteria. Among recurrent abnormalities, the t(15,17) translocation uniformly characterizes promyelocytic AML12. This translocation fuses the PML gene (chromosome 15) with RARA (chromosome 17), generating the PML-RARA fusion protein, which disrupts cellular differentiation and contributes to APL pathogenesis. In our series, this cytogenetic abnormality was found in 67% of patients, either alone or in association with other anomalies—a prevalence comparable to or slightly lower than that reported in the literature.

Risk stratification in APL using the Sanz score, which is based on leukocyte and platelet counts, remains the most reliable method for promptly identifying high-risk patients. Although the Sanz risk score was initially developed as a tool to predict APL relapses13, it has also demonstrated prognostic value for early mortality14. Patients are classified into three risk groups, with a leukocyte count ≥10,000/mm³ considered an indicator of higher risk for both early death and relapse in APL9,10,15.

Regarding Treatment, there is a general consensus on the use of high-dose anthracyclines combined with all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), while the addition of cytarabine during induction remains a subject of debate. A randomized study demonstrated better outcomes with the cytarabine-daunorubicin combination compared to daunorubicin alone, and other data suggest a benefit of cytarabine in patients with leukocytosis >10,000/mm³16,17.

Central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis is recommended for high-risk patients or those presenting with cerebral hemorrhage at diagnosis or during induction18.

Historically, APL is the AML subtype for which maintenance regimens were developed9. However, recent protocols combining ATRA and arsenic trioxide (ATO) have shown excellent results without a maintenance phase, challenging its routine necessity19. In our cohort, only one patient was treated according to the APL2000 protocol, which included maintenance therapy.

The development of targeted therapies has been made possible by advances in understanding oncogenic mechanisms and treatment resistance. Over the past two decades, APL treatment has been revolutionized by the introduction of ATRA and ATO, which respectively target RARα and PML, two components of the PML-RARα oncoprotein specific to APL20. Several multicenter trials have demonstrated that the ATRA + ATO strategy, without chemotherapy, achieves very high complete remission rates (>95%) and superior event-free and overall survival compared to traditional regimens combining ATRA and chemotherapy in standard- and intermediate-risk patients. Furthermore, the emergence of oral arsenic formulations facilitates outpatient management and may reduce costs and hospitalization duration, while showing comparable efficacy to intravenous ATO21.

Nevertheless, access to these treatments remains challenging in resource-limited countries such as Morocco. The low number of pediatric cases results in limited availability in hospital pharmacies, and medications often need to be obtained through temporary use authorizations (ATU), causing critical delays. Additionally, access to transfusion support care-essential for managing hemorrhagic complications in APL-remains a major logistical challenge.

In our cohort, after the first induction, the complete remission (CR) rate was 63.6%, and the partial remission (PR) rate was 27.2%. These rates are lower than those reported in studies by Powell et al. and Park et al., where CR rates were 83% and 86.8%, and PR rates were 6% and 5.2%, respectively7,22. However, the CR rate after completion of chemotherapy (two inductions and three consolidations) was 91% in our series, which aligns with results observed in studies using ATRA combined with cytotoxic agents (anthracyclines + cytarabine).

The relapse rate in APL varies depending on the treatment regimen used. In our cohort, using a protocol combining ATRA with chemotherapy, the relapse rate was 20% (n=2). This rate is higher than those reported in studies using similar regimens, notably by Imaizumi et al. (3.6%) and Park et al. (7.1%)7,11. This discrepancy may be attributed to the limited number of patients in our series. Despite therapeutic advances, early mortality remains a major challenge in APL. In our cohort, it was 16.6%, consistent with rates reported in pediatric studies (ranging from 3.4% to 17.6%)1,7,8,9,11. Hemorrhage was identified as the leading cause of death.

Overall survival (OS) and event-free survival (EFS) in our series were 83% and 72%, respectively. These results are comparable to literature data showing OS and EFS rates of 90% and 71%7,9,10,11.

Initial white blood cell count is a significant factor influencing both OS and EFS. In our cohort, OS and EFS were 100% and 86.6% for patients with a leukocyte count ≤10,000/mm³, compared to only 33.3% for those with counts >10,000/mm³. This prognostic factor has also been reported in other studies7,9.

Conclusion

Acute leukemia is the most common pediatric cancer in many low-income countries, including Morocco. Among its subtypes, acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) has been identified by the WHO as a priority disease due to its high prevalence and the potential to achieve high cure rates with standardized treatment. In contrast, acute myeloid leukemia (AML), though less frequent in children, remains a significant therapeutic challenge, particularly in resource-limited settings.

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), however, represents a turning point in the management of acute leukemias. Once feared for its aggressiveness and high early mortality, it is now one of the most curable forms of leukemia, thanks to the introduction of targeted therapies such as ATRA and arsenic trioxide (ATO), which enable complete and durable remissions without the systematic use of intensive chemotherapy. Ongoing clinical trials are currently evaluating chemotherapy-free protocols.

To ensure optimal care, it is essential to pool pediatric and adult hematology resources, particularly through informal adult hematology networks, to guarantee continuous availability of ATRA and arsenic. Although APL stands as a model of therapeutic success, its full effectiveness depends on timely treatment initiation and access to supportive care, two conditions that remain fragile in our context. Strengthening training programs, interdepartmental coordination, and drug supply systems is critical to making these advances accessible to the most vulnerable children.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

License

© The Author(s) 2025.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, and unrestricted adaptation and reuse, including for commercial purposes, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

References

-

Testi AM, D’Angiò M, Locatelli F, et al. Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL): comparison between children and adults. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2014 Apr 15;6(1):e2014032.

-

Zwaan CM, Kolb EA, Reinhardt D, et al. Collaborative efforts driving progress in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2015 Sep 20;33(27):2949-62.

-

Gurnari C, Voso MT, Girardi K, et al. Acute promyelocytic leukemia in children: a model of precision medicine and chemotherapy-free therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Jan 11;22(2):642.

-

Lo-Coco F, Avvisati G, Vignetti M, et al. Retinoic acid and arsenic trioxide for acute promyelocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jul 11;369(2):111-21.

-

de Rooij JD, Zwaan CM, van den Heuvel-Eibrink M. Pediatric AML: from biology to clinical management. J Clin Med. 2015 Jan 9;4(1):127-49.

-

Khoury JD, Solary E, Abla O, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization classification of haematolymphoid tumours: myeloid and histiocytic/dendritic neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022 Jul;36(7):1703-19.

-

Park KM, Yoo KH, Kim SK, et al. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes of childhood acute promyelocytic leukemia in Korea: a nationwide multicenter retrospective study by Korean Pediatric Oncology Study Group. Cancer Res Treat. 2022 Jan;54(1):269-76.

-

Andrade FG, Feliciano SVM, Sardou-Cezar I, et al. Pediatric acute promyelocytic leukemia: epidemiology, molecular features, and importance of GST-theta 1 in chemotherapy response and outcome. Front Oncol. 2021 Mar 19;11:642744.

-

Testi AM, Biondi A, Lo Coco F, et al. GIMEMA-AIEOP AIDA protocol for the treatment of newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) in children. Blood. 2005 Jul 15;106(2):447-53.

-

Ortega JJ, Madero L, Martín G, et al. Treatment with all-trans retinoic acid and anthracycline monochemotherapy for children with acute promyelocytic leukemia: a multicenter study by the PETHEMA Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Oct 20;23(30):7632-40.

-

Imaizumi M, Tawa A, Hanada R, et al. Prospective study of a therapeutic regimen with all-trans retinoic acid and anthracyclines in combination with cytarabine in children with acute promyelocytic leukaemia: the Japanese Childhood Acute Myeloid Leukaemia Cooperative Study. Br J Haematol. 2011 Jan;152(1):89-98.

-

Grimwade D. The pathogenesis of acute promyelocytic leukaemia: evaluation of the role of molecular diagnosis and monitoring in the management of the disease. Br J Haematol. 1999 Sep;106(3):591-613.

-

Sanz MA, Lo Coco F, Martín G, et al. Definition of relapse risk and role of nonanthracycline drugs for consolidation in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia: a joint study of the PETHEMA and GIMEMA cooperative groups. Blood. 2000 Aug 15;96(4):1247-53.

-

Lou Y, Ma Y, Sun J, et al. Effectivity of a modified Sanz risk model for early death prediction in patients with newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2017 Nov;96(11):1793-800.

-

Testa U, Lo-Coco F. Prognostic factors in acute promyelocytic leukemia: strategies to define high-risk patients. Ann Hematol. 2016 Apr;95(5):673-80.

-

Sanz MA, Grimwade D, Tallman MS, et al. Management of acute promyelocytic leukemia: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2009 Feb 26;113(9):1875-91.

-

Adès L, Sanz MA, Chevret S, et al. Treatment of newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL): a comparison of French-Belgian-Swiss and PETHEMA results. Blood. 2008 Feb 1;111(3):1078-84.

-

Montesinos P, Díaz-Mediavilla J, Debén G, et al. Central nervous system involvement at first relapse in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with all-trans retinoic acid and anthracycline monochemotherapy without intrathecal prophylaxis. Haematologica. 2009 Sep;94(9):1242-9.

-

Kutny MA, Alonzo TA, Abla O, et al. Assessment of arsenic trioxide and all-trans retinoic acid for the treatment of pediatric acute promyelocytic leukemia: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group AAML1331 trial. JAMA Oncol. 2022 Jan 1;8(1):79-87.

-

de Thé H, Le Bras M, Lallemand-Breitenbach V, et al. The cell biology of disease: acute promyelocytic leukemia, arsenic, and PML bodies. J Cell Biol. 2012 Jul 9;198(1):11-21.

-

Huang DP, Yang LC, Chen YQ, et al. Long-term outcome of children with acute promyelocytic leukemia: a randomized study of oral versus intravenous arsenic by SCCLG-APL group. Blood Cancer J. 2023 Dec 5;13(1):178.

-

Powell BL, Moser B, Stock W, et al. Arsenic trioxide improves event-free and overall survival for adults with acute promyelocytic leukemia: North American Leukemia Intergroup Study C9710. Blood. 2010 Nov 11;116(19):3751-7.