A Rare Case of Pediatric Cervical Ganglioneuroblastoma: Diagnostic Challenges and Surgical Management

Abstract

Ganglioneuroblastomas are commonly found in the extracranial region, but in the head and neck region, it is a very rare disease. For patient evaluation, diagnostic modalities like CT scan with contrast, MRI, and fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) can help, but the accuracy for definitive diagnosis is very limited. In this report, we present the case of a 4-year-old male who presented with a slow-growing neck mass, along with multiple enlarged cervical lymph nodes. His workup raised a suspicion of ganglioneuroblastoma, which was later confirmed histopathologically. The patient was treated surgically, which included resection of the neck mass and cervical lymph node dissection. No recurrence was observed at 6 months and 1-year follow-up. This report aims to contribute to existing literature by discussing diagnostic challenges, imaging findings, and surgical management of this rare tumor, providing insights into optimal clinical approaches.

Key Words: pediatric cervical neuroblastic tumors, neuroblastic tumors, ganglioneuroblastoma, pediatric neck mass, cervical ganglioneuroblastoma

Introduction

The International Neuroblastoma Pathology Classification divides the peripheral neuroblastic tumors into neuroblastomas, ganglioneuromas, and ganglioneuroblastomas. Among the neuroblastic tumors, approximately 20% are represented by ganglioneuroblastomas. There is a range of cellular differentiation exhibited by them, from immature neuroblasts to mature ganglion cells, and this spectrum of differentiation bridges the gap between neuroblastomas and ganglioneuromas1,2. Both mature ganglion cells and immature neuroblasts make up these tumors, and there is a higher incidence noted among males and individuals of Caucasian descent3.

Among the extracranial tumors in children, peripheral neuroblastic tumors are the most common presentation. These tumors rank third among the most frequently diagnosed pediatric malignancies, following leukemias and central nervous system cancers3,4. The origin of these tumors is from neural crest cells, and they can develop anywhere along the sympathetic nervous chain. Approximately 8-10% of all childhood neoplasms, which affect children between the ages of 0 to 4 years, are represented by neuroblastic tumors. These include cervical, thoracic, and pelvic tumors1,5. These tumors most frequently present in the adrenal gland as a mass in approximately 35% of cases. These tumors also occur as a retroperitoneal mass in 30% of the cases. Among the retroperitoneal mass presentations, 20% appear in the posterior mediastinum, and around 2-3% appear in the pelvic region6.

The typical presentation is of a neck mass, which is sometimes detected incidentally during radiological investigations. However, the early detection can be challenging due to these lesions’ indolent and slow-growing nature. These cervical masses can be evaluated by imaging techniques, which provide insights into their size, location, composition, and their relationship with the surrounding structures. However, these modalities cannot reliably distinguish ganglioneuroblastomas from other neurogenic tumors. Valuable diagnostic information is offered by fine-needle aspiration biopsy, but it does not always yield a definitive histopathologic diagnosis. In order to make a conclusive diagnosis of ganglioneuroblastoma, surgical resection, followed by a comprehensive histopathological examination, is warranted7.

In the literature, especially from low and middle-income countries, the reported cases of ganglioneuroblastomas are infrequent. In this case report, the presentation of a 4-year-old male with a neck mass to a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan is discussed. This neck mass was later diagnosed as a rare subtype of ganglioneuroblastoma, nodular ganglioneuroblastoma, which was located in the cervical region, which is an even rarer site of presentation. This report aims to explore the presentation of this uncommon case of ganglioneuroblastoma, along with its clinical features and the surgical outcomes.

Case Report

A 4-year-old male presented to the general pediatric clinic with progressively enlarging multiple neck masses on the right side over the past two years. He had no known comorbidities, and the mass was not associated with any constitutional symptoms. There were no pressure symptoms such as dyspnea or dysphagia at the time of presentation.

On examination, multiple enlarged cervical lymph nodes were palpable on the right side. The nodes were firm, with the largest measuring approximately 4 × 4 cm, while the others ranged from subcentimeter to 1.5 cm in size. None were adherent to the overlying skin. The patient had previously undergone an incisional biopsy of the neck mass at another hospital, which was reported as benign reactive lymphadenopathy.

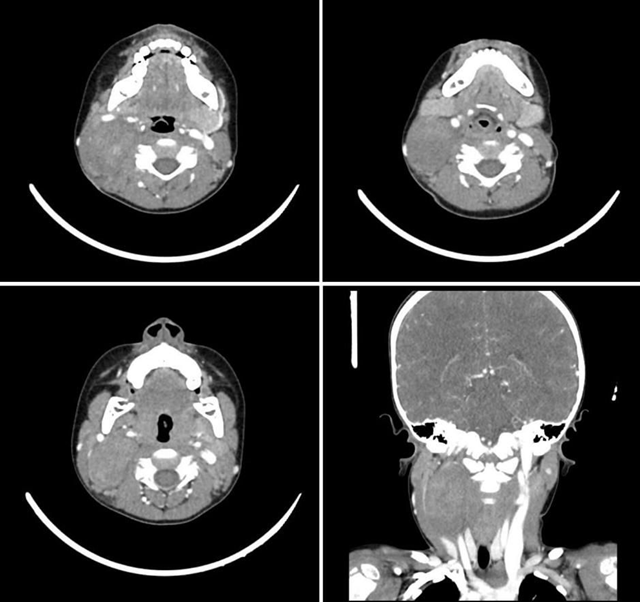

Contrast-enhanced CT and MRI imaging of the neck revealed a large, well-defined isodense area seen in the posterior right neck, measuring 57 x 35 x 30 mm, showing heterogeneous contrast enhancement. The lesion contained foci of calcification and demonstrated increased vascularity, with imaging features highly suggestive of a paraganglioma (Figure 1). Multiple enlarged but benign-appearing lymph nodes were also noted at levels II and III on the right side. The lesion caused splaying of the external and internal branches of the right common carotid artery and compression of the internal jugular vein (IJV). It exhibited an isointense signal on T1- and T2-weighted sequences with homogeneous intense enhancement on post-contrast sequences.

Figure 1 – CT Scan imaging

Upon request, the previously biopsied lymph node tissue blocks were re-evaluated, revealing a small focus of ganglion-like cells and Schwannian stroma, raising suspicion of metastatic ganglioneuroblastoma. A contrast-enhanced CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis ruled out metastatic deposits.

Surgical excision of the tumor was carried out (Figure 2). The mass was located inside the carotid sheath, displacing the carotid artery medially and the internal jugular vein (IJV) laterally, with the mass arising from a nerve. Multiple enlarged lymph nodes were also present and excised during the procedure.

Figure 2 . Preoperative picture of the lesion

Figure 3 . Intraoperative picture of the lesion

No immediate or delayed post-operative complications, including hematoma, wound dehiscence, or nerve weakness, were observed. The patient remained vitally stable and was discharged home in a stable condition on operative day 2. Histopathological analysis showed a well-circumscribed encapsulated lesion comprising schwannian stroma along with ganglion cells in various stages of maturation, with features favouring the diagnosis of GNB, intermixed type 6 x 4x 2.5 cm in size, with an intact capsule. A total of 11 lymph nodes were excised, 4 of which tested positive for metastasis. A fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) study for N-MYC gene amplification was negative. The patient was followed closely during follow-up visits. Upon 6 -month and 1 year follow-up, the patient did not show any signs or symptoms of recurrence.

Discussion

Ganglioneuroblastoma is classified as a malignant tumor due to the presence of primitive neuroblast interspersed among mature ganglion cells. They are generally considered less aggressive compared to neuroblastomas. Reports of ganglioneuroblastoma are limited8. Most patients, around 90%, are diagnosed with ganglioneuroblastoma before the age of 5, with the average age of diagnosis being about 4 years old. Rarely, patients may be diagnosed over the age of 109.

Preoperative clinical symptoms are essential in assessing patients. Peripheral GNBs of cervical origin often present with respiratory symptoms due to airway compression. These symptoms can range from mild snoring to severe respiratory distress 6,10. Additional symptoms include dysphagia or nerve palsies, caused by the tumor’s compressive effects. Specific presentations, such as Horner’s syndrome or iridocyclitis, can also be diagnostic 6.

In the pediatric population, isolated cervical masses are a rare presentation of neuroblastic tumors. When they do occur, these masses are typically benign, with common examples being fibromas, lipomas, or hemangiomas. Malignant cervical masses are more likely to be lymphomas or leukemias 6. Occasionally, the malignancy may be metastatic, as seen in cases of GNB or other neural tumors6,10. GNBs arise along the sympathetic chain due to a developmental deficiency of neuronal cells. While they are usually sporadic, a family history of neuroblastic tumors is significant in 1-2% of cases, with inheritance involving autosomal dominant alleles9.

Daneshbod et al. reported a case in which fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) successfully identified ganglioneuroblastoma, while a case series by Manjlay et al. found FNAC to be non-diagnostic8. Zeng et al. recommends that for an accurate diagnosis of GNB, a core needle biopsy or immunohistochemistry should be performed before undergoing surgery11. ERBB3 has recently emerged as a clear-cut marker of GNB in gene expression and IHC studies12. Another study that focused on IHC findings revealed that positive anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) mutations indicated poor prognosis in patients with GNB13. Without these modalities, diagnosis remains a challenge, especially due to a lack of established guidelines for these tumors. However, clinical presentation in conjunction with advanced imaging modalities can play a helpful role in guiding the diagnostic process6. Among imaging techniques, CT scans are particularly valuable, offering detailed insights into the tumor’s size, primary origin, extent of invasion, lymphadenopathy, and the presence of calcifications9.

After the primary diagnosis is established, staging investigations such as serum catecholamines and urinary levels of homovanillic acid (HVA) and vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) can serve as biochemical markers, detecting ganglioneuroblastoma in approximately 60% of cases. For disease surveillance, catecholamine levels can act as a useful indicator as they are elevated in case of recurrence8.

MRI is the preferred modality of investigation over CT scan for its superior diagnostic precision, offering enhanced tissue contrast and detailed visualization of tumor characteristics in the parapharyngeal space5.

Managing patients with ganglioneuroblastoma necessitates a multidisciplinary approach, which includes surgical excision, chemoradiotherapy, and/or biological therapies. Several key factors influence the management option, including the patient’s age, tumor stage, and spread of the tumor in the neck. Surgical resection remains the cornerstone of treatment, with meticulous attention to preserving vital structures. In cases where complete excision is not achievable, chemotherapy is often employed as an adjunctive measure to mitigate residual disease. Neck lymph node dissection, particularly selective dissection, is recommended even in the absence of metastasis on imaging or clinical examination6.

Chemotherapeutic regimens, including agents such as doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, platinum-based compounds, and etoposide, have demonstrated efficacy in treating neuroblastic tumors. Emerging therapies, including the use of immunomodulators and retinoids, offer promising potential for advancing the future treatment landscape of ganglioneuroblastoma6.

Conclusion

In a child presenting with neck mass, ganglioneuroblastoma should be included in the differential diagnosis after ruling out common pathologies, especially in younger patients with a lesion in the parapharyngeal space. In these cases, a biopsy is the gold standard investigation to ensure an accurate diagnosis and a complete surgical excision preserving all the vital structures is needed.

Competing Interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Licence

© Author (s), [2026].

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, and unrestricted adaptation and reuse, including for commercial purposes, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

References

-

Tatekawa Y, Yamanaka H, Hasegawa T, Yamashita Y. An unusual location and presentation of a cervical ganglioneuroblastoma. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol Extra. 2013;8(3):86–8.

-

Erol O, Koycu A, Aydin E. A Rare Tumor in the Cervical Sympathetic Trunk: Ganglioneuroblastoma. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2016;2016:1454932.

-

Decarolis B, Simon T, Krug B, Leuschner I, Vokuhl C, Kaatsch P, et al. Treatment and outcome of Ganglioneuroma and Ganglioneuroblastoma intermixed. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):1–11.

-

Jackson JR, Tran HC, Stein JE, Shimada H, Patel AM, Marachelian A, et al. The clinical management and outcomes of cervical neuroblastic tumors. J Surg Res. 2016;204(1):109–13.

-

McGann EK, Goldberg AM, Lelegren MJ, Pickle JC, Bak MJ, Mark JR. Primary cervical ganglioneuroblastoma, nodular subtype. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2022;49(5):889–92.

-

Lu D, Liu J, Chen Y, Chen F, Yang H. Primary cervical ganglioneuroblastoma: A case report. Medicine. 2018;97(12).

-

Gasparini A, Jiang S, Mani R, Tatta T, Gallo O. Ganglioneuroma in Head and Neck: A Case Report of a Laryngeal Ganglioneuroma and a Systematic Review of the Literature. Cancers. 2024;16(20):3492.

-

Manjaly JG, Alexander VRC, Pepper CM, Ifeacho SN, Hewitt RJ, Hartley BEJ. Primary cervical ganglioneuroblastoma. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;79(7):1007–12.

-

Badiu Tișa I, Samașca G, Aldea C, Lupan I, Farcau D, Makovicky P. Ganglioneuroblastoma in children. Neurol Sci. 2019;40(9):1985–9.

-

Zeng Z, Liu J, Xu S, Qin G. Ganglioneuroblastoma in the Retropharyngeal Space: A Case Report and Literature Review. Ear Nose Throat J. 2022

-

Wilzén A, Krona C, Sveinbjörnsson B, Kristiansson E, Dalevi D, Øra I, et al. ERBB3 is a marker of a ganglioneuroblastoma/ganglioneuroma-like expression profile in neuroblastic tumours. Mol Cancer. 2013;12(1).

-

Duijkers FAM, Gaal J, Meijerink JPP, Admiraal P, Pieters R, De Krijger RR, et al. High anaplastic lymphoma kinase immunohistochemical staining in neuroblastoma and ganglioneuroblastoma is an independent predictor of poor outcome. Am J Pathol. 2012;180(3):1223–31.