Aspiring engineer who would be a cancer specialist

Introduction

This is the life story of an engineering student who became a cancer specialist after he lost his father to cancer.

Background

I was born in an Armenian family in Lebanon. My parents were 8 and 6 when they left their birthplace in Turkey during the First World War. After several months they arrived in Aleppo and then moved to Beirut, Lebanon. I was a naughty boy for which I was punished at school so often that I did not want to go to school anymore. Then, my parents took me to Hovaguimian-Manougian secondary school for boys. I entered the principal’s office with mixed feelings. As if he was reading my emotions and thoughts, Mr. Ara Topjian, the principal of the school said “My son, if you have come because your parents forced you, we do not need more students; however, if you are here to learn, you are in the best place.” It was a transformative experience for me. For the first time, I was treated as a human being rather than an object to be molded. I attended that school until graduation 6 years later; I was not reprimanded or punished a single time. I became the first in my family to graduate from high school. Looking at my grades, Mr. Topjian told me that I could pursue any major in science at the university. I decided to study engineering so that I could work in construction with my father and brothers.

My father, who was a carpenter by trade believed strongly in good work ethics. As a contractor, he employed Syrian farmers. As a gift, these farmers brought him tobacco leaves. He smoked until he died from throat cancer at the age of 65. The cancer was advanced when it was diagnosed. Three months after radiotherapy, his belly got bigger and two months later, he passed away in my arms. I was in the sophomore class at the time. When I found out how little they could do to help my father, I decided to become a physician. I graduated from the American University of Beirut Medical School in June of 1971.

For lack of financial support to specialize, I went to Saudi Arabia to work as a family physician in Aramco’s Dhahran Health Center. Four months in this position, my American nurse, who had worked in the clinic for 8 years, told me that I was not like the other physicians, that I was too good to work in that clinic, and it would be better for me to specialize in the States. She repeated the same advice for months. Finally, I gave in and with her help, I completed 15 applications for internship training positions in the USA. In January 1972. I received 3 offers for the straight medical internship; one of them was from St. Louis City Hospital which I accepted.

The training program in that Hospital was run by 2 universities. The program run by Washington University was superior to that run by St. Louis University to which I was accepted. The foreign medical graduates accepted into the internship program were required to reside in the hospital. That allowed me to volunteer when help was needed on the medical ward. Six months in the program, I was called in by Dr. John Vavra, head of the service run by Washington University. He told me that he has been following the new interns in the hospital and was very impressed by the dedication and compassion I showed to my patients. He let me know that if I agreed to do my first-year residency at Washington University service at the City Hospital, he would accept me for a second-year residency program at Washington University Medical Center. I accepted his offer.

In the fall of 1974, when I was working in the emergency room at Barnes Hospital a patient who had a seizure in the bus was brought in. He had a blue face and was unconscious. After proper intervention, his condition improved. During the observation period, I checked him regularly. Past midnight, he called me to his bedside to thank me for taking good care of him. He said, he had admired my composure during the emergencies and that he was impressed with my genuine interest in the welfare of my patients. Then he inquired about my plans. I told him about my interest in cancer research. I informed him that I was offered a medical oncology fellowship at the University of Miami, but I preferred the training program at MD Anderson Cancer Center, from which I had not received a response yet. It turned out that he was a surgeon. He told me that he would write to Dr. Copeland, the head of the surgical department at Anderson Hospital so that one way or the other, they inform me about the status of my application. A month later, he sent me Dr. Copeland’s response to his letter, in which the latter said that he “shared his testimonial letter with the Chairman of the Department of Developmental Therapeutics and that I should expect a response soon.” A few weeks later, I was offered a fellowship position without an interview.

I started my fellowship in medical oncology in July 1975. Under Dr. Freireich’s guidance and supervision. I learned how to evaluate new anticancer drugs through clinical trials. The clinician, researcher, and teacher I became is the result of his approach to cancer management i.e. that investigative therapy is the best promising therapy for advanced cancer, that when possible treatment should be given with a curative intent, and lastly, that listening to the patients is the best learning tool. During my career, I found the 3 approaches essential for my success as a clinical investigator and for fulfilling the 3 missions of the Cancer Center i.e. research, therapy, and education.

Post Fellowship experience

In the late 1970s, Medical oncology was a new branch of internal medicine. The practice was quite limited in scope and frustrating. We had a couple of dozens of cytotoxic agents to use in combinations to treat adult solid tumors. The therapy for common adult cancers was of marginal efficacy. The need for clinical trials to find effective new drugs was very high. Patient participation in clinical trials required establishing a positive interaction between the patient and the caregiver, and it depended on the respect shown to the patient’s dignity, beliefs, and social values. In addition, clinical trials required gauging the explanation of treatment options to the patient’s ability to understand, to have him involved in the treatment decisions. It also required a show of assurance that the physician would be there for the patient in time of need. The physician had to listen carefully to what the patient was saying to collect pertinent clinical data.

In the summer of 1982, I decided to leave Houston and work in a place closer to Lebanon to be able to assist my family members throughout the ongoing civil war. With that in mind, I went to Memphis to be interviewed for a position at King Faisal Specialist Center. Three days later, I was offered the position and a month later I was in Riyadh. After 9 years, when the civil in Lebanon ended, I decided to return to Houston. I was interviewed for a position in GI medical oncology service at MD Anderson Cancer Center. After the interview, I was told they had 4 additional candidates to interview before deciding who would fill the open position. Two weeks later, I met Dr. Michael Keating, with whom I had done my fellowship while attending cancer congress in Florida. He asked me when I would be returning to Houston. I told him about my interview with the GI Oncology department. He said Dr. Robert Benjamin has an open position in the Melanoma/Sarcoma department and added, that he will let him know of my desire to return to Houston. Two weeks later, I was offered a position in the Melanoma department without an interview.

Speaker Pro Tempore Terry E. Haskins of the House of Representatives of the State of South Carolina I met Rep. Haskins in 1996 when he came to MD Anderson Cancer Center for consultation regarding the management of his recurrent malignant melanoma. His primary skin cancer and regional recurrence were treated surgically in 1973 and 1995 respectively. In 1996, he had metastases involving the lungs. I treated him with biochemotherapy, including cisplatin, vinblastine, dacarbazine, interferon, and interleukin-2 (IL-2). He received this therapy for 3 months and achieved complete remission. Unfortunately, his disease came back in October 1998. I treated him with biochemotherapy for 5 months this time and achieved a complete response for the second time. Then, he went to John Wayne Cancer Clinic in Santa Monica, California to receive a melanoma vaccine. Unfortunately, he died of brain metastases on October 24, 2000.

Top of Form Bottom of Form

During one of the biochemotherapy treatments in the fall of 1998, Terry developed severe hypotension. He lost consciousness and had a multi-organ failure on the last day of his treatment on Friday afternoon. Given the expected decreased number of caregivers during the week-end, I decided to spend the night at his bedside. He was too unstable to be transferred to the intensive care unit which was located on a different floor in an adjacent building. Throughout the night, I monitored his vital signs, and urine output and adjusted the rate of administration of dopamine drip to maintain adequate perfusion of his vital organs. On Saturday afternoon, his blood pressure recovered, his organ functions improved and he woke up. He noticed my presence next to him and asked what I was doing in the hospital when I had no week-end duty. I told him he had a rough night because of hypotension. He thanked me for staying to help him recover. Then, he started asking questions about my education, ethnic background, and relatives in Lebanon. Although I felt uneasy, I wanted him to talk so that I evaluate the recovery of his mental functions. I told him that I was the son of Armenian orphans collected by American missionaries from the Syrian desert during the genocide of 1915. The Turks justified the massacres of Armenians claiming that they were collaborating with Russians, I mentioned that my parents were from a town near Konya more than 550 miles to the west of the Russian border. I added that American missionaries and diplomatic personnel witnessed the massacres. Even though the related documents were collected in the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, the American government has not officially recognized the Armenian Genocide for geopolitical, military, and economic considerations. Terry asked me to get him literature that described the events. I provided him 3 books written by prominent American historians who were experts on the subject.

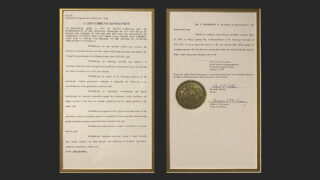

In February 1999, I learned that Terry had revealed that he was receiving therapy for metastatic melanoma under my care during a session of the House of Representatives of the State of South Carolina. In April, he told me that he had worked closely with Rep. Jeff E. Smith to have the Armenian Genocide recognition bill passed by both the South Carolina House and Senate. In mid-1999, I was presented with a framed copy of H. 3678, the Concurrent Resolution that states that “the members of the General Assembly recognize April 24, 1999, as South Carolina Day of Remembrance of the Armenian Genocide of 1915-1923 to honor the memory of the one and one-half million people of Armenian ancestry who lost their lives during that terrible time …” (Appendix A) This was the outcome of the persistent effort of Rep. Terry Haskins, who fought for justice, selflessly and for no personal benefit. It is important to remember that this recognition happened 25 years before President Biden recognized the Armenian Genocide.

I worked in that department until I retired about 10 years ago. We delivered standard systemic therapies and investigated new drugs as part of clinical trials. These investigative therapies provided the patient access to new promising drugs. At times these drugs had a transformative impact on the patients’ lives. For example, in 2002 when scientists discovered that the BRAF gene had activating mutations in about half of all cutaneous melanomas, it led to the discovery of new drugs such as vemurafenib and dabrafenib which were administered orally, less toxic and induced responses 3 times more often than IL-2 which was given IV on the inpatient service. Similarly, an improved understanding of how cancer cells place a brake that controls the immune response to cancer led to the development of monoclonal antibodies that removed the inhibition (Checkpoint inhibitors ipilimumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab) that revolutionized the treatment of metastatic skin melanoma increasing the median survival of these patients from 5 months in the 1980s to 5 years in the last decade.

Two-thirds of the patients we saw at the Cancer Center were referred from outside Houston, The physicians at our hospital provided phone consultation service to doctors and patients who contacted them for advice. I always made myself available and, cognizant of the fact that cancer diagnosis affects patients and their families in numerous ways. Very often, I was contacted by strangers and often I did not hear from them again. On a few occasions, they let me know that my advice had a life-changing impact on them.

Assisting patients or families with cancer was not limited to me. My colleagues in the institution devote time and effort to assisting patients, families, and doctors to make the delivery of cancer care safe and improve the outcome of cancer treatment. Given my experience a few decades back, when I found that the patients benefited more from my listening to them, and addressing the issues that had bothered them than the chemotherapy I could prescribe. I received thanks from many patients and families for being there for them and having a positive impact on the quality of their lives.

The case of a woman with melanoma calling before Christmas

One such occasion was related to a young mother from Florida who had just returned home after seeing her oncologist. She was treated for metastatic melanoma for over 2 years. During her last visit to her oncologist, they discussed the need to make end-of-life arrangements as her disease had become resistant to the treatments her oncologist could deliver. She called me from her family room two days before the Christmas of 1998. She was distraught about the future of her children. After inquiring about her medical history and making a list of treatments she had received, it became clear that there was only one drug left for her to try. It was interleukin-2. She told me that her doctor told her this drug was very toxic and it may shorten her life because of serious side effects. I emphasized that it was given under close monitoring in the hospital to reduce the chances of serious organ damage. I tried to convince her that she would not survive without that therapy. Sobbing while watching her young children play; she was insisting that I was leading her death. I ended up suggesting that her oncologist should make an appointment for her with Dr. Steven Rosenberg at NIH, in Bethesda MA. He has the most experience in delivering interleukin-2 therapy and if she is accepted to his program, NIH will take care of the transportation and treatment bills. I concluded that would be her best decision.

Five years later I received a phone call from the Melanoma clinic. The nurse told me that a lady was frantically looking for me. She said she refused to give her the letter she had for me. I met her in the clinic. She was the mother-in-law of the melanoma patient who had called me years before.

She was visiting the Breast Cancer Center for consultation. She gave me the envelope saying “My daughter-in-law insisted that I meet you in person to thank you for patiently listening to her when she called for advice.” I opened the envelope and took out the card, it said: “I do not know if you remember, 5 years ago, a few days before Christmas, I called you for advice related to my metastatic melanoma. After our discussion, I followed your advice and went to NIH for treatment with IL-2 under the supervision of Dr. Rosenberg. I achieved complete remission. The last evaluation completed 2 months ago showed no signs of disease recurrence. I wanted you to know that I am very appreciative of you taking the time to convince me to take IL-2 that day. God bless you.”

An Opportunity to Give Back

My father had a seasonal job as a contractor. He built mansions and vacation homes. in the spring and summer when it rained less. When I got accepted for freshman class at AUB, I applied for need-based scholarships. I got only a work-in-aid scholarship that required me to work as an assistant to the security guard at the sea gate of the university’s private beach. The life at the gate was brutal in the winter. The icy cold wind froze the humidity on my face. I was at the gate when we heard of President Kennedy’s assassination. We all wept. As the winter was coming to its close, I sent more applications for scholarships. To my great delight, I was offered one from the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU). It came a few months after my father had passed away. That lifeline came at a crucial time in my college education. It made it possible for me to dream big and change my major from engineering to medicine to become a cancer specialist.

Thirty-seven years later, just before Christmas of 2000, I received a call from the office of President Louise Manoogian-Simone. She said: “Excuse me for intruding; we wouldn’t have called you if we had an alternative. AGBU Armenia Medical Program has a young physician with cancer in Yerevan. We have sent the pathology slides to MD Anderson to get confirmation of diagnosis but received nothing in the past 2 months. We are seeking your assistance in this matter as the patient’s condition is deteriorating.” On further inquiry, I found that he had weight loss, night sweats, and fever. A biopsy was taken from his abdominal mass. The local pathologist had diagnosed the case as lymphoma.

I traced the pathology slides and took them to a pathologist colleague and asked him if he could give me a preliminary verbal diagnosis as a favor. He looked at the slides under the microscope and said, “This is not lymphoma, it is testicular cancer.” Immediately, I called the AGBU office and suggested that they do a blood test to measure the serum Beta-HCG and alpha-fetoprotein levels; the tumor markers that are often elevated in cases with metastatic testicular cancer. A day later, I was informed that the Beta-HCG level was over 200000. Mrs. Simone told me that the patient was no longer fit to travel to New York for treatment. She asked me if I could help. I told her I would be in New York to see my daughter in a few days and that I would pass by the AGBU office to find what resources are available in Yerevan. After inquiry, I told Mrs. Simone that the drugs and expertise needed to treat this patient with multi-organ failure were locally inadequate to treat this patient. I stressed the fact that we have only one shot to stop and reverse the deterioration in this patient. Then Mrs. Simone told me she was willing to provide everything I needed if I took charge and treated this patient to enable him to come to New York to continue his treatment. I asked for the help of a person in Yerevan who is willing to administer the drugs as per my instructions and would inform me about the condition of the patient twice a day via email. I gave her a list of drugs that should be sent to Armenia ASAP. The following day, Dr. Armine Kharatyan, an anesthesiologist volunteered to assist me in the administration of chemotherapy. On January 1, 2000, we gave him doxorubicin and cyclophosphomide at reduced doses. Three weeks later, when his serum creatinine returned to normal, cisplatin was added to the regimen. Within 6 weeks, there was significant clinical improvement. The patient was offered to continue his treatment in New York. He declined, preferring to continue his therapy close to his family. Later his therapy regimen was changed to avoid peripheral neuropathy and pulmonary damage. His beta HCG returned to normal levels by mid-2000. However, the CT scans showed necrotic lesions in the lungs, liver, and abdomen. To prevent the possible persistence of viable cancer cells in these lesions, their surgical removal was recommended.

When chemotherapy was discontinued, I received a letter from Mrs. Simone in which she said ” Words are not adequate to express our appreciation for all the advice and tremendous medical care you provided to Dr. K.D. It is not often one is fortunate enough to find such a combination of devotion and expertise in a volunteer. I hesitate to use the word volunteer since efforts on behalf of K. were of the highest level…. he received the finest medical care possible because of you. Please know we are eternally grateful to you.”

The patient underwent abdominal and thoracic surgery in Houston. The microscopic examination of the surgical specimens showed no viable cancer cells. He had follow-up evaluations in Yerevan for 5 years and remained free of tumor recurrence. Then all tests were discontinued.

On August 18, 2010, I received an e-mail from him which said “I climbed Mount Ararat. I dedicated it to the 2 persons who gave me life; my Mother and you, my doctor. I reached a peak height of 5,135 meters above sea level. It was difficult. It is at 5,000 meter level, that the eternal ice starts. With love, K.” The last time I saw Dr. K.D. was in Yerevan in June 2016. He was practicing plastic surgery. He remains free of cancer as of Christmas last year. Thanks to the unwavering determination of Mrs. Louise Manoogian-Simone, Armenian children are living a normal life without the stigma of cleft lips, cleft palates, and club feet due to expert surgical procedures performed by Dr. K.D.

Progress in the treatment of melanoma

Progress in the treatment of metastatic cancer happened in small bouts separated by long pauses until 2 decades ago. In the 80s when we had a couple of dozen drugs to treat solid tumors, its efficacy against the common cancers was quite limited. Occasionally few patients achieved complete response and a small fraction remained disease-free for a few years. We saw them for a yearly follow-up evaluation. Some of these patients shared their happy milestones like the birth of babies, anniversaries, graduations, etc. as a token of appreciation. At difficult times, such as after losing a patient, those photographs pinned on the board facing my workroom inspired and pulled us from the depths of our despair. Over time, slowly initially, the space on my board started filling. During the past 3 decades the pace of filling increased exponentially thanks to the availability of IL-2 in the 1990s, the Targeted therapies, and checkpoint inhibitors in the first decade of the 21st century. Thanks to these new drugs, we saw survivors of metastatic skin melanoma so often that it necessitated the creation of a Long-term follow-up clinic dedicated to them in 2014. The creation of this long-term survivors’ clinic is the happiest event in my career.

Additional reading

- Agop Y. Bedikian MD and Margaret A. Bedikian: Commemorating Genocide: Return to the White City – Akshehir. The Armenian Mirror-Spectator: April 19, 2018

- Agop Y. Bedikian. An Ethical Dilemma with a Happy Ending. The Armenian Mirror-Spectator, May 24, 2018

- Agop Y. Bedikian Commemorating Genocide: Background to Recognition of the Armenian Genocide by the South Carolina House and Senate. The Armenian Mirror-Spectator April 19, 2018.

License

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

© Agop Y Bedikian, 2024. This license permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.