Osteomyelitis in Children with Sickle Cell Disease: Is MRI pathognomonic?

Abstract

Introduction: Sickle cell disease (SCD) is one of the most common genetic blood disorders in Oman, with an incidence of around 6% of the population. SCD patients are at high risk of getting osteomyelitis (OM). The method of choice for diagnosing OM is by obtaining a positive blood culture and a bone/joint biopsy. However, a negative blood culture does not exclude the diagnosis of OM, and bone biopsy is an invasive procedure that is not routinely performed in all patients.

Standard Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is recognized as the study of choice for confirming OM in normal populations and has been reported to have high sensitivity and specificity. However, in patients with SCD, due to significant bone infarcts, it’s challenging to differentiate from bone infections, with MRI sensitivity and specificity of around 82% and 75%, respectively, as reported. An ambidirectional study was done to evaluate the role of clinical, laboratory, and radiological parameters in establishing the diagnosis of OM in children with SCD.

Methodology: Fifty-one SCD patients with a mean age of 9 years were recruited. The inclusion criteria of our study are all patients with SCD aged from 6 months to 18 years, suspected to have OM, and involvement of the limb or joint. Clinical, laboratory, and radiological findings were collected and grouped into two groups: OM vs VOC patients.

Results: In our study, the sensitivity of MRI alone was 29.6% in detecting OM. Cortical destruction was found in only 12.5% of patients who had an MRI, which confirms the diagnosis of OM. Combined with Clinical and laboratory data, the likelihood of diagnosing osteomyelitis increases significantly.

Conclusion: In SCD patients, it is usually difficult to distinguish between OM and VOC. In many cases, the MRI findings were either inconclusive or led to an incorrect diagnosis. Combining clinical, laboratory, and radiological data might increase the likelihood of diagnosing OM in these patients.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is one of the most common genetic blood disorders in Oman. It’s an autosomal recessive disorder caused by inheriting a mutation in the hemoglobin-beta gene on chromosome 11 from both parents. The incidence of the disease in Oman is around 6% of the population1. Those patients are vulnerable to crisis episodes in their disease, with the major types of crises grouped as aplastic, acute sequestration, hyper-hemolytic, and Vaso-occlusive crises2. Vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs) remained the leading cause of hospitalized patients with sickle cell disease3.

Patients with VOCs present with bony pains mainly in the limbs, followed by back, chest, and abdominal pain4. SCD patients are at high risk of getting osteomyelitis (OM) due to the impaired immune response, because of functional hyposplenia combined with recurrent bone infarction with VOC5. Salmonella species are the most common pathogens causing osteomyelitis in SCD, whereas Staphylococcus aureus is the most common cause in the normal population. Limb or joint VOCs are sometimes associated with fever, making differentiation from osteomyelitis difficult. Both conditions may present almost identically, with pain, fever, swelling, local redness, and leukocytosis6.

The method of choice in diagnosing OM is to obtain a positive blood culture and bone/joint biopsy. However, a negative blood culture does not exclude the diagnosis of OM, and bone biopsy is an invasive procedure that is not routinely performed in all patients4.

Standard Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is a gold standard tool in confirming OM in normal populations and has a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 96% according to previous reports5. Other radiological modalities have also been used to aid in the diagnosis of OM, such as bone scan, with a sensitivity reaching 79-100% and a specificity of 79%7.

However, in patients with SCD, it is not usually an easy task, as patients with significant bone infarcts are challenging to differentiate from bone infections, as the MRI sensitivity and specificity drop to 82% and 75% respectively, as reported5.

There have been multiple studies to evaluate different radiological investigations to aid in the diagnosis of OM in SCD patients, such as CT scan, US, Bone scan, and a combination of more than one radiological modality.

In our local experience at Sultan Qaboos University Hospital (SQUH), we encountered numerous instances of both false positive and false negative results. Notably, almost 4 of our patients were not diagnosed with OM using standard MRI with fat suppression sequencing (subtraction method); however, their clinical course confirmed the diagnosis of OM with abscess formation and even development of sequestrum.

The current study aims to evaluate the role of clinical, laboratory, and radiological parameters in establishing the diagnosis of OM in children with SCD.

Methodology

This is an ambidirectional study with 26 patients’ data collected as retrospective and 37 patients collected as prospective, based on data collection from Electronic Patient Records (EPR) of Sultan Qaboos University Hospital (SQUH) of all patients presented with signs and symptoms suggestive of osteomyelitis for a 9-year duration, from April 2013 to October 2022.

The primary objective is to evaluate different parameters: clinical, laboratory, and radiological, in establishing the diagnosis of OM in SCD.

The secondary objective is to determine the organisms’ growth, antibiotic choice, duration, and correlation with genotypes.

Parental informed consent was obtained, clarifying that there are no limitations in any part of the investigations and management provided.

All patients who presented to the hospital during the study period were included; 63 patients were screened after obtaining informed consent.

The inclusion criteria of our study are patients with SCD aged from 6 months to 18 years, both sexes, suspected to have OM, and involvement of the limb or joint.

The exclusion criteria were that Patients were excluded from the study if they did not have a confirmatory test for SCD in the hospital, and repeated visits for the same complaint.

After exclusion, a total of 51 patients with SCD, for whom it was challenging to differentiate between osteomyelitis and Vaso-occlusive crises clinically, were included in this study.

For all patients included in the study, clinical assessment of signs and symptoms suggestive of osteomyelitis; laboratory investigations including CBC, acute-phase reactants, cultures (Blood/aspiration fluid), and Imaging, including plain X-rays, US & MRI. Some patients underwent standard MRI, while others had post-contrast-enhanced MRI with subtraction, which was used to evaluate suspected cases of osteomyelitis.

Clinical Data were extracted from the “Trackcare” system, collected using the “Microsoft Excel” Program, and then analyzed using SPSS version 28.

Radiological Data were extracted with the help of a Pediatric radiologist who is having more than 10 years of experience in Musculoskeletal imaging from “The Philips” radiology system used in SQUH who had identified the five most common radiological findings that can be found in VOCs and OM in SCD patients which are bone edema, infarction, subperiosteal edema, collection and cortical destruction with the presence of the last one is considered to be definitive for OM.

The Clinical, laboratory, and radiological data were combined, and the patients were divided into three groups based on the likelihood of OM (Table 1). Definitive OM suggests the diagnosis of OM over other causes. Possible OM has features suggesting OM, but can’t exclude VOC, and requires treatment with antibiotics and imaging if not already done. While unlikely, OM is favoring VOC more than bone infection.

Table 1: Proposed definition of Definitive, Possible & Unlikely OM

| A | B |

|---|---|

| Definitive OM | Possible OM with microbiologic confirmation (from blood or tissue), OR cortical destruction on MRI, OR drainage of purulent fluid from surgical intervention (Tissue diagnosis), OR later development of chronic osteomyelitis |

| Possible OM | Fever with tenderness and swelling at the site of suspected infection AND abnormal inflammatory marker (CRP > 50 OR WBC >15) AND Persistence of skeletal symptoms > 1 week without microbiologic confirmation, cortical destruction, or drainage of purulent fluid or later development of chronic osteomyelitis |

| Unlikely OM | Suspected OM based on fever, tenderness, and swelling at the site of pain, but otherwise does not fulfill the criteria for definitive or possible OM |

Results

Of the 51 patients enrolled in this study (Details in Appendix 1), 54% (28) were male, with an average age of 9 +/- 4 years. OM was the admitting diagnosis in 28 of them, VOC in 17 patients, and six patients had other diagnoses, such as septic arthritis or ‘impending fracture’. Twenty-three (45%) patients had HB SS, followed by 13 (25%) with HB Sβ0, and 23% with HB Sβ+.

98% of patients presented with pain, and 94% had tenderness over the bone/joint involved. 86% of the patients had erythema around the affected limb. Thirty patients had swellings, and only 34% had heat in the affected limb. These signs of infection have been grouped as low risk of OM by the presence of 2 local signs of infection (swelling and tenderness), and as high risk by the presence of >28. 66% of patients were in the high-risk group. Of interest, 80% of the patients presented with or developed fever during admission, and only 37% had a high WBC count, defined as > 15×109/L.

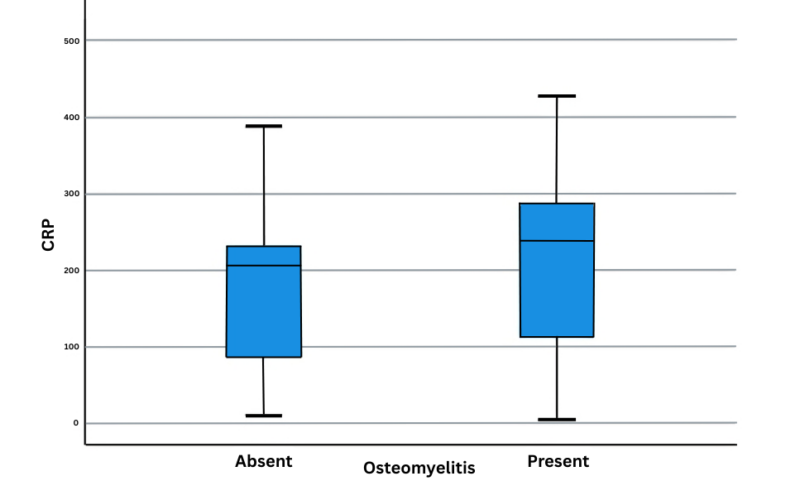

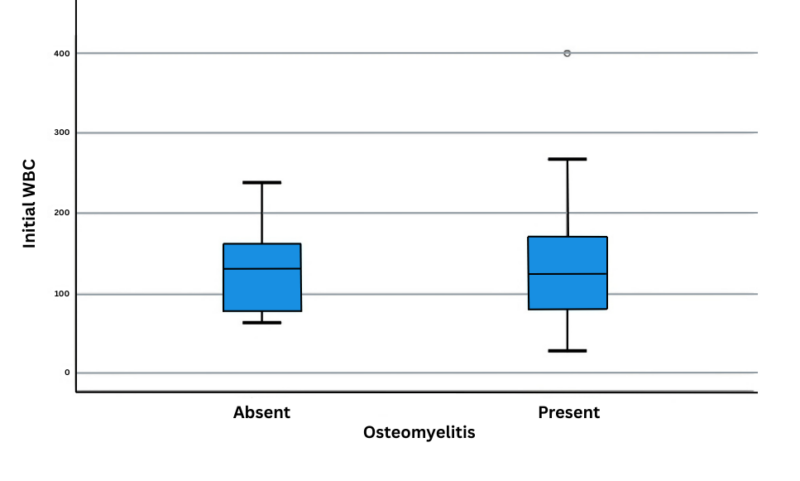

Also, there was no difference between the OM and VOC groups regarding inflammatory markers (Figures 1 and 2). The difference in the initial CRP values was not statistically significant (P=0.23) (Table 2).

Figure 1: CRP with osteomyelitis

Figure 2: Initial WBC with osteomyelitis

Table 2: CRP with osteomyelitis diagnosis

| Osteomyelitis | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRP | Absent | 19 | 166.05 | 103.784 | 0.23 |

| CRP | Present | 21 | 207.81 | 111.734 | 0.23 |

We applied a clinical score proposed by Al Shukaili et al8 (Table 3). This defined a median score of 6-8 as an equivocal difference between VOC and OM. In the current study, a median score above 6 favors OM.

Table 3: Clinical score provided in Al Shukaili et al Study

| A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Parameter Score | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Fever | No | >38 and < 38,5 | >38,5 |

| Duration of fever 38.2 | <2 days | 2-3 days | >3 days |

| Localized Signs of Infection | None | Swelling and tenderness | Plus Redness, Hotness, Fluctuation |

| No. of site involved | >1 | <1 | - |

| WBCs | Normal | - | >15 |

| Loss of function (walking, writing, etc) | No | - | Yes |

| Blood culture | Negative | - | Positive |

MRI was done for 34 patients, 97% of them found to have bone edema & infarction. 94% of them had subperiosteal edema, and around 44% developed periosteal collection. Around 11% of them developed cortical destruction (Table 4).

Table 4: MRI Findings in patients enrolled in the study

| MRI Findings | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Bone edema | 33 | 97% |

| Bone infarction | 33 | 97% |

| Subperiosteal edema | 32 | 94% |

| Subperiosteal collection | 15 | 44% |

| Cortical destruction | 4 | 11% |

Those radiological findings were grouped as less probable OM (probable), highly probable OM (definitive), and equivocal (suspected)9. The images were reviewed independently by two radiologists, and they agreed that the presence of cortical destruction was suggestive of OM, while the presence of bone edema, infarction, and subperiosteal edema was more in favor of VOC. The presence of the periosteal collection was equivocal and needed a clinical correlation for a definitive diagnosis of OM vs VOC.

Based on that, 8% of patients who had an MRI were diagnosed with OM, while 70% were in favor of VOC, and 22% (11) were equivocal. On follow-up, only 4 of them proved to be osteomyelitis.

The clinical score, when joined with the radiological outcome, showed that the high-risk group of radiological outcomes (i.e., cortical destruction) had a higher clinical score. Overall, this finding was not significant with a p-value of 0.475 (Table 5).

Table 5: Radiological outcome with osteomyelitis

| Radiological outcome | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 35 | 5.60 | 1.14 | 0.475 |

| Equivocal | 11 | 5.36 | 1.62 | 0.475 |

| High | 4 | 6.25 | 0.50 | 0.475 |

| Total | 50 | 5.60 | 1.22 | 0.475 |

Blood culture was collected in all patients except one, as it was missed to be obtained when the patient presented in the emergency department; there was a positive blood culture in 9 of them, with six having grown Salmonella, the other 3 had a growth of S. aureus, Citrobacter freundii, and Bacteroides fragilis each. Notably, one patient with positive Salmonella in the blood culture and a clinical course suggestive of OM had an MRI report that was strongly suggestive of a VOC. Moreover, this patient had bony changes highly indicative of OM in an X-ray taken 1 week after admission.

Fifteen patients required surgical intervention. Five of these patients exhibited growth in the aspirated fluid, with Salmonella growth identified in two cases, followed by growth of MRSA, Enterobacter cloacae & Bacteroides fragilis in one patient each.

Five patients were not started on antibiotics and showed dramatic improvement with analgesia and hydration. All remaining patients started on antibiotics, with most of them on multiple antibiotics. Ceftriaxone was administered to 42% (38) of the patients, and Ciprofloxacin in 19% (17) of them as a discharge medication. Other antibiotics were also used, such as vancomycin, Flucloxacillin, and Clindamycin, on special occasions when MRSA was isolated.

In our study, patients with OM, as identified by MRI, have a sensitivity of 29.6% and a specificity of 69.5% compared to clinical diagnosis, with positive predictive value and negative predictive value of 53.3% and 45.7%, respectively.

Discussion

Patients with SCD presenting with bony pain and fever are most likely to have VOC, but OM can’t be excluded; early detection will help in preventing the sequelae of not treating OM appropriately. Diagnosis of OM in SCD remained one of the top challenges, as the clinical presentation is similar to VOC, with local signs of infections shared between the two groups. Also, blood culture can aid in the diagnosis if positive, as the sensitivity of it in diagnosing OM is only 42%10, but it can’t rule it out if negative.

In our study, only 17% of proven OM patients had positive blood culture; the explanation for the low yield might be due to the start of oral antibiotics in some febrile patients before reporting to the hospital. Moreover, the Canadian Pediatric Society is identifying Kengella Kingae as the most common pathogen in children younger than 4 years, which was not reported in our population, as it needs special media for growth11.

We have also shown that Salmonella and S. aureus remain the most common organisms causing OM, which aids in selecting an appropriate antibiotic regimen. Ceftriaxone alone was a suitable choice for treating OM, combined with Vancomycin in patients with a previous history of MRSA, or other anti-staphylococcal antibiotics in MSSA-suspected cases.

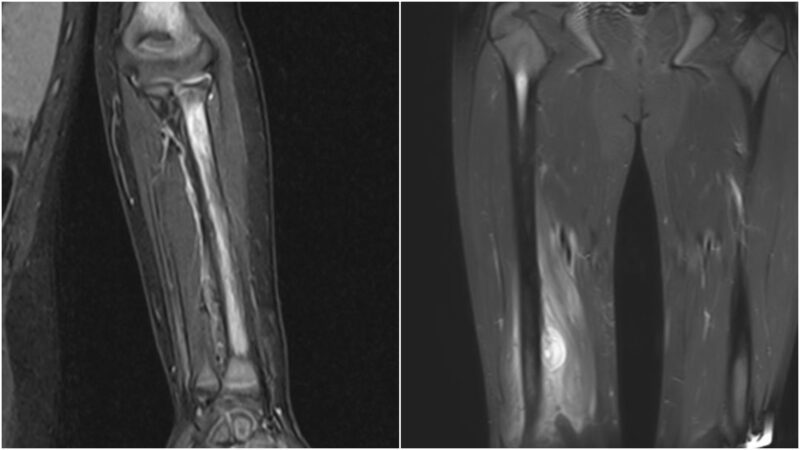

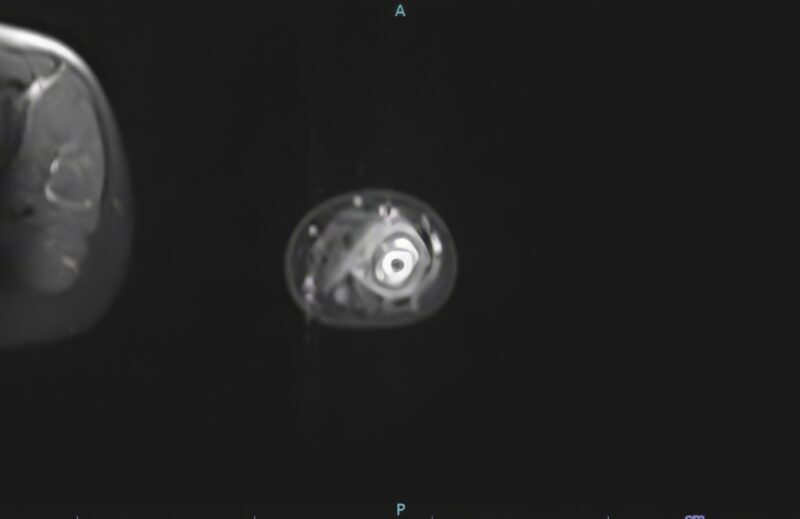

In SCD, the radiological findings in diseased bones, which include bone infarction and edema as a result of limited blood supply and recurrent VOCs, might trigger an inflammatory response locally and cause subperiosteal edema, which can be misinterpreted as infection (Figures 3 and 4). The breakdown of the cortex (Figure 5) by the pus indicates the acuity of the inflammatory process in the bone due to neutrophilic infiltration in response to bone marrow invasion by microorganisms, which indicates OM.

Figures 3 and 4: Bone edema and subperiosteal collection

Figure 5: Cortical break

Many radiological modalities have been studied to help in the diagnosis. A combination of Technetium and gallium scintigraphy has been studied by T. Amundsen and his colleagues in 1984 and shown to be effective in diagnosing OM in SCD12. It was also studied in 1988 by C. Kahn and his colleagues at the University of Chicago Medical Centre13. U/S has been studied by M. Booz in Bahrain, as the subperiosteal fluid > 10 mm is indicative of OM.

This has been studied locally by R. Wiliam, etc. in 1999 as the presence of subperiosteal fluid > 4 mm is indicative of OM, which will require further imaging for confirmation, with a sensitivity and specificity of 74% and 63%, respectively14,15. U/S has been combined with Laboratory data and concluded by B. Inusa as a reliable and cost-effective diagnostic tool that will need further scans for confirmation16.

In 2023, M. Scruggs and his team had a case report discussing different imaging modalities aiding in the diagnosis of OM in SCD including x-rays, bone scan, MRI & PET scan; discussing those modalities, x-rays usually will be normal in the first few days and will start to show changes after the first week of infection, bone scan is having high sensitivity as discussed earlier but the specificity is reaching to 35%. It can be lower if there is any high osteoblastic activity in the bone17.

MRI has been studied lately to differentiate between OM and bone infarction. J. Delgado concluded that T1-W fat-saturated MRI imaging alone is not a reliable method18. C. Kao has combined microbiologic and radiologic features and concluded that this approach has increased the likelihood of identifying a definitive diagnosis of OM9.

The lower sensitivity of MRI in our paper may be attributed to several factors. For instance, receiving antibiotics before imaging can impact the inflammatory response in the bone. Furthermore, the MRI days allocated for the pediatric population are limited to 2 days/week.

PET-CT scans is a type of nuclear scan that uses Fluorine‐18 fluorodeoxyglucose which is detecting high glucose uptake by hypermetabolism, it had many advantages in terms of a quick turnaround time of 1.5–2 h, optimal spatial resolution, high target‐to‐background contrast, accurate anatomical localization of sites of abnormality, whole‐body coverage, lack of artifacts due to metallic hardware, and absence of reactions due to administered pharmaceuticals19. Hence, it has high sensitivity and specificity, reaching 90% and 85%, respectively. A study using this scan showed changes in clinical management by 67%, and they stated that “it is not warranted, as the outcome is frequently no change in management.”20

Inflammatory markers are an indicator of bacterial infections. It was reported that a CRP rise of> 50 mg/dL is an indicator of acute bacterial infections21. Also, a WBC count of more than 15×109/L has a sensitivity of 47% and specificity of 76% for serious bacterial infections22.

In our population, we observed a higher prevalence of OM among males than females, which may be attributed to the disease’s nature and the absence of estrogen’s role in nitric oxide production. Nitric oxide plays a crucial role at the vascular level in preventing vascular phenomenon-related crises in SCD23.

Conclusion

The strength of our study is the large group collected over 9 years. Additionally, clinical, laboratory, and radiological findings are utilized to categorize patients into definitive, possible, and unlikely OM as shown in Table 1. Being an ambidirectional type of study is also a strength. The study’s limitations include its focus on patients at a single hematology center and the lack of imaging for some patients due to technical issues.

We recommend expanding the sample size by doing a multi-center study to study the validity of the proposed definition of definitive OM.

In conclusion, with the development of the most accurate & cutting-edge technology, MRI has been significant. Still, radiological diagnosis of OM in SCD remains a challenge. Combining clinical, laboratory & radiological data is crucial to prevent missing OM in this vulnerable group of children. Clinical resolution of signs of inflammation within a short period, less than 1 week, is highly indicative of VOC rather than OM.

Competing Interests: The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this study.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

License

© Author(s) 2025.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, and unrestricted adaptation and reuse, including for commercial purposes, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Appendix

| No. | Sex | Age | Chief complain | Genotype | Swelling | Tenderness | Erythema | Hottness | Fever | WBC | ANC | CRP | Culture | Antibiotic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 14 | RT thigh swelling | Hb S/B0 | + | + | - | + | - | 4 | 2.3 | 41 | No growth | Ceftriaxone |

| 2 | F | 7 | Fever and lethargy | Hb SS | - | + | - | - | + | 26.7 | 23.2 | 230 | No growth | Vancomycin + Ceftriaxone |

| 3 | M | 15 | Back pain | Hb SS | - | + | - | - | + | 14.6 | 12.5 | 11 | No growth | Ceftriaxone + Cloxacillin+ Flucloxacilline |

| 4 | F | 9 | Chest and back pain | Hb SS | - | + | - | + | + | 8.4 | 6.6 | 130 | No growth | Ceftriaxone + Ciprofloxacin |

| 5 | F | 3 | Back pain | Hb SS | - | + | - | - | + | 17.3 | 12.4 | 135 | No growth | Ceftriaxone + Ciprofloxacin |

| 6 | M | 2 | Reduced activity and walking | Hb S/B0 | - | - | - | - | + | 15.7 | 7.3 | 205 | No growth | Ceftriaxone + Ciprofloxacin |

| 7 | F | 10 | Bilateral Lower limbs pain | Hb SS | - | + | - | - | + | 8.6 | 4 | 235 | No growth | Ceftriaxone + Vancomycin + Metronidazole + Cloxacillin + Clarithromycin + Azithromycin |

| 8 | M | 16 | Bilateral upper and lower limb pain | Hb SS | - | + | - | - | + | 16.1 | 12.8 | 43 | No growth | Ceftriaxone + Ciprofloxacin + Cloxacillin + Vancomycin + Azithromycin |

| 9 | M | 14 | Bilateral LL pain | Hb S/B0 | + | + | - | - | + | 5.4 | 4 | 24 | No growth | Ceftriaxone |

| 10 | M | 4 | Right forearm pain | Hb SS | + | + | + | + | + | 16.8 | 8.5 | 55 | No growth | ceftriaxone + ciprofloxacin |

| 11 | F | 16 | Lower limbs pain | HB S/B+ | - | + | - | - | + | 7.7 | 4.6 | 38 | No growth | Ceftriaxone+ clindmyocine2then clindamycin and cipro |

| 12 | M | 13 | Lower back + RT UL + LT leg + LT sided chest pain | Hb SS | + | + | - | - | + | 12.9 | 10.7 | 184 | No growth | Ceftriaxone |

| 13 | F | 2 | Cough and fever | Hb S/B+ | + | + | - | - | + | 10.1 | 3.6 | 427 | Salmonella | Ceftriaxone + Ciprofloxacin |

| 14 | F | 7 | Fever and LT shoulder pain | Hb S/B0 | - | + | - | - | + | 12.4 | 9.8 | 76 | Salmonella | Ciprofloxacin + Ceftriaxone + Vancomycin |

| 15 | M | 4 | Bilateral UL pain with swelling in LT and RT forarm | Hb S/B+ | + | + | - | - | + | 16 | 8 | 37 | Salmonella | Ciprofloxacin |

| 16 | M | 13 | right wrist pain and fever | Hb S/B0 | + | + | + | - | + | 20.6 | 18.8 | 144 | S. Aures | flucloxacillin + cloxacillin |

| 17 | M | 9 | left thigh tenderness | Hb S/B0 | + | + | - | + | + | 20 | 10 | 268 | No growth | Ceftriaxone + vancomycin then ciprofloxacin |

| 18 | F | 14 | fever and right hip pain | Hb SS | + | + | + | - | + | 21.4 | 14.7 | 102 | No growth | meropnam + gentmyocin then ciprofloxacin |

| 19 | F | 8 | fever and right leg pain | Hb S/B+ | + | + | - | + | + | 11.7 | 6.6 | 300 | Citrobacter Frendii | cefpim |

| 20 | M | 5 | back pain 2 days and fever 10 days | Hb SS | + | + | - | - | + | 7.7 | 3 | 10 | No growth | Ceftriaxone + ciprofloxacin |

| 21 | F | 3 | left arm swellwing | HB S/B+ | + | + | + | + | + | 18.5 | 12.1 | 353 | Bacteroides Fragilis | iv ceftriaxone and metronjdazole |

| 22 | F | 12 | fever, generlized body pain and pain at both Upper limbs | Hb S/B+ | + | + | - | - | + | 6.3 | 4.7 | 247 | No growth | Meropenam + teicoplanin then ciprofloxacin + clindamycin |

| 23 | F | 7 | left elbow pain | Hb S/B+ | + | + | - | + | - | 7.9 | 4.9 | 9 | No growth | ciprofloxacin |

| 24 | F | 5 | Bilateral hip joint pa | Hb SS | - | - | - | - | + | 7.8 | 3.8 | 81 | No growth | Ceftriaxone + Vancomycin + Erythromycin |

| 25 | F | 15 | Generalized body ache, jaw pain, headache, back and abdominal pain | Hb SS | + | + | - | - | + | 18.2 | 14.7 | 44 | No growth | N/A |

| 26 | M | 3 | Lower back and bilateral LL pain | Hb SS | + | + | + | + | + | 6.4 | 2.9 | 11 | No growth | Ceftriaxone + Vancomycin |

| 27 | M | 9 | LT leg pain | Hb S/B0 | + | + | - | - | + | 15.4 | 9.7 | 208 | No growth | Ceftriaxone |

| 28 | F | 1 | LT elbow swelling and fever | Hb SS | + | + | - | + | + | 15.4 | 3.7 | 64 | No growth | Ceftriaxone + Vancomycin |

| 29 | M | 18 | Bilateral leg and RT thigh swelling | Hb S/B0 | + | + | - | - | + | 13 | 8.7 | 166 | No growth | Tazocin |

| 30 | F | 2 | RT LL pain and inability to bear weight | Hb SS | - | + | - | - | - | 13.9 | 5 | 13 | No growth | - |

| 31 | M | 8 | Lower back, abdomen and bilateral UL + LL pain | Hb S/B+ | + | + | - | - | + | 22.4 | 17.5 | 101 | No growth | Ceftriaxone + Vancomycin + |

| 32 | M | 11 | back pain and rt lower limb pain | Hb S/B0 | - | // | - | - | + | 19.8 | 14.5 | 111 | No growth | ceftriaxone |

| 33 | M | 8 | pain in left arm | Hb S/B0 | + | + | - | - | - | 7.3 | 3.8 | 12 | No growth | - |

| 34 | M | 13 | fever, right thigh ain and swelling | Hb SS | + | + | - | + | + | 11.4 | 6.9 | 212 | No growth | ceftriaxone + cefuroxime |

| 35 | F | 8 | bilateral thigh pain with fever | Hb SS | - | + | - | + | + | 23.8 | 19.7 | 275 | No growth | Ceftriaxone + Vancomycin then ciprofloxacin |

| 36 | M | 5 | Right elbow pain | Hb SS | + | + | - | - | + | 20.6 | 14.1 | 12 | No growth | ceftriaxone |

| 37 | F | 5 | Right arm pain | Hb S/B+ | + | + | - | + | + | 14.5 | 12.2 | 52 | No growth | ceftriaxone |

| 38 | F | 10 | right thigh pain | HB SS | + | + | - | - | - | 13.3 | 10.1 | 233 | No growth | ceftriaxone |

| 39 | M | 13 | lower limb pain | HB S/B+ | + | + | - | + | + | 7.7 | 6 | 9 | No growth | ceftriaxone |

| 40 | M | 2 | Painful LT elbow swelling | Hb S/B0 | + | + | - | + | - | 22.2 | 8.2 | 23 | No growth | Ceftriaxone |

| 41 | M | 2 | Reduced activity and walking | Hb S/B0 | - | - | - | - | + | 15.7 | 7.3 | 205 | No growth | Ceftriaxone + Ciprofloxacin |

| 42 | M | 14 | RT thigh swelling | Hb S/B+ | + | + | - | + | - | 4 | 2.3 | 41 | No growth | Ceftriaxone |

| 43 | M | 13 | RT UL + LT leg pain | Hb SS | + | + | - | - | + | 12.9 | 10.7 | 184 | No growth | Ceftriaxone |

| 44 | F | 7 | left elbow pain | + | + | - | + | - | 7.9 | 4.9 | 9 | No growth | ciprofloxacin | |

| 45 | M | 12 | left ankle joint pain | Hb SS | + | + | + | - | + | 12 | 10.5 | 316 | Salmonella | Ceftriaxone + Rifampin |

| 46 | M | 3 | Lt upper limb pain | HB S/B+ | + | + | - | + | + | 16 | 9.9 | 77 | No growth | Ceftriaxone + clindamicin then ciprofloxacin + cotrimoxazole |

| 47 | F | 5 | Rt shoulder swelling | Hb S trait | + | + | + | // | 12 | 7.2 | 321 | Salmonella | Cefotaxime then ciprofloxacin | |

| 48 | M | 2 | LT leg pain | Hb S trait | + | + | - | + | 12.4 | 5.8 | No growth | Ceftriaxone | ||

| 49 | F | 13 | lower limb pain | Hb SS | - | + | - | - | // | 11.1 | 7 | 387 | No growth | ceftriaxone +clindamycin |

| 50 | M | 14 | RT thigh swelling | Hb S/B0 | + | + | - | + | - | 6.8 | 3.9 | 24 | MRSA | Ceftriaxone |

| 51 | F | 7 | Fever and lethargy | Hb SS | - | + | - | - | + | 2.7 | 2.2 | 40 | no growth | Ceftriaxone |

References

-

Al-Kindi RM, Kannekanti S, Natarajan J, et al. Awareness and attitude towards the premarital screening programme among high school students in Muscat, Oman. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2019;19(3):e217-e224.

-

Juwah AI. Types of anaemic crises in paediatric patients with sickle cell anaemia seen in Enugu, Nigeria. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89(6):572-576.

-

Yale SH, Nagib N, Guthrie T. Approach to the vaso-occlusive crisis in adults with sickle cell disease. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(5):1349-1356, 1363-1364.

-

Berger E, Saunders N, Wang L, Friedman JN. Sickle cell disease in children: differentiating osteomyelitis from vaso-occlusive crisis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(3):251-255.

-

Al Farii H, Zhou S, Albers A. Management of osteomyelitis in sickle cell disease: review article. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2020;4(9):e20.00002-10

-

da Silva Junior GB, Daher EDF, da Rocha FAC. Osteoarticular involvement in sickle cell disease. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2012;34(2):156-164.

-

Fritz JM, McDonald JR. Osteomyelitis: approach to diagnosis and treatment. Phys Sportsmed. 2008;36(1):nihpa116823.

-

Al Shukaili AK, Al Kharusi AA, Tbaileh E, et al. Clinical and magnetic resonance imaging decision making rules in differentiating vaso-occlusive crises from osteomyelitis in paediatric sickle cell population: is MRI pathognomonic? Blood. 2019;134(Suppl 1):4824.

-

Kao CM, Yee ME, Maillis A, et al. Microbiology and radiographic features of osteomyelitis in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(10):e28517.

-

White LM, Schweitzer ME, Deely DM, Gannon F. Study of osteomyelitis: utility of combined histologic and microbiologic evaluation of percutaneous biopsy samples. Radiology. 1995;197(3):840-842.

-

Le Saux N. Diagnosis and management of acute osteoarticular infections in children. Paediatr Child Health. 2018;23(5):336-343.

-

Amundsen TR, Siegel MJ, Siegel BA. Osteomyelitis and infarction in sickle cell hemoglobinopathies: differentiation by combined technetium and gallium scintigraphy. Radiology. 1984;153(3):807-812.

-

Kahn CE, Ryan JW, Hatfield MK, Martin WB. Combined bone marrow and gallium imaging: differentiation of osteomyelitis and infarction in sickle hemoglobinopathy. Clin Nucl Med. 1988;13(6):443-449.

-

Booz MMY, Hariharan V, Aradi AJ, Malki AA. The value of ultrasound and aspiration in differentiating vaso-occlusive crisis and osteomyelitis in sickle cell disease patients. Clin Radiol. 1999;54(10):636-639.

-

William RR, Hussein SS, Jeans WD, Wali YA, Lamki ZA. A prospective study of soft-tissue ultrasonography in sickle cell disease patients with suspected osteomyelitis. Clin Radiol. 2000;55(4):307-310.

-

Inusa BPD, Oyewo A, Brokke F, Santhikumaran G, Jogeesvaran KH. Dilemma in differentiating between acute osteomyelitis and bone infarction in children with sickle cell disease: the role of ultrasound. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e65001.

-

Scruggs M, Pateva I. Multifocal osteomyelitis in a child with sickle cell disease and review of the literature regarding best diagnostic approach. Clin Case Rep. 2023;11(7):e7288.

-

Delgado J, Bedoya MA, Green AM, Jaramillo D, Ho-Fung V. Utility of unenhanced fat-suppressed T1-weighted MRI in children with sickle cell disease: can it differentiate bone infarcts from acute osteomyelitis? Pediatr Radiol. 2015;45(13):1981-1987.

-

Schooler GR, Davis JT, Daldrup-Link HE, Frush DP. Current utilization and procedural practices in pediatric whole-body MRI. Pediatr Radiol. 2018;48(8):1101-1107.

-

Kumar R, Basu S, Torigian D, et al. Role of modern imaging techniques for diagnosis of infection in the era of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21(1):209-224.

-

Nehring SM, Goyal A, Patel BC. C-reactive protein. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Accessed Dec 24, 2023.

-

De S, Williams GJ, Hayen A, et al. Value of white cell count in predicting serious bacterial infection in febrile children under 5 years of age. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(6):493-499.

-

Kim-Shapiro DB, Gladwin MT. Nitric oxide pathology and therapeutics in sickle cell disease. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2018;68(2-3):223-237.