Survival and Challenges with Multimodal Treatment in Children with Rhabdomyosarcoma – Real Scenario from A Resource-limited Center of Bangladesh

Abstract

Background: The management of Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) in children is complex and challenging. Multi-modality treatment, which consists of surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation therapy, is used in a risk-stratified approach. RMS is a common malignancy among children in the National Institute of Cancer Research and Hospital (NICRH). Here, multi-modal treatment can be applied in one-step settings, but with diverse obstacles. The study was conducted to assess the survival outcomes of children with RMS and to identify challenges with a risk-stratified treatment strategy.

Methodology: The prospective observational study was conducted in the Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Department of NICRH, Bangladesh, from January 2016 to December 2020. Children up to 18 years of age of both sexes with a diagnosis of RMS were included consecutively. After risk stratification, treatment was assigned to each risk group. Outcomes were defined as remission, relapse, refractoriness, Death, or dropping out on the last follow-up. Survival was analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method. Challenges encountered sequentially during treatment were identified and broadly categorized into those related to surgery, radiotherapy (RT), chemotherapy (CT), treatment adherence, and disease outcome. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 23.

Results: The study enrolled 146 children with RMS. Males were predominant (84), and the age ranged from 0.33 to 17 years, with a mean of 6.1years ± 4.7 SD. The low-risk group comprised 16.4%, the intermediate-risk group 68.5%, and the high-risk group 15.1%. Challenges related to surgery occurred in 51.3%, RT-related challenges in 26.0%, and chemotherapy-related challenges were found in 21.9%. Treatment irregularities were 20.5%, and 60.3% patients received non-multimodal treatment, further adding to the difficulties. Complete remission was achieved in 20.5% and the remaining 65.1% died, 3.4% relapsed, and 11% dropped out. By the Kaplan-Meier method, OS was 26.9% and EFS was 23.1%, with a mean OS time of 43.5 months ±3.5 SE (95%CI 36.4-50.4) and a mean EFS of 36.1 months ±3.5 SE (95% CI 29.1-43.0), respectively, over a median follow-up of 24.0 (range,1 to 108) months.

Conclusion: The study found a high rate of mortality and relapse, with a suboptimal survival rate. Major challenges with the management of RMS were related to local treatment modalities.

Introduction

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is the most common soft tissue sarcoma, accounting for 3.5% of all malignant neoplasms in children aged 0 to 14 years and 2% in those aged 15 to 19 years1,2. The management of RMS is complex and challenging due to its aggressive growth pattern, high metastatic potential, disease heterogeneity, and evolving treatment regimens. Moreover, a lack of molecular testing facilities, limited investigation facilities, and advanced-stage disease make the scenario more challenging for the limited-resource countries like Bangladesh. Children with RMS require multi-modality treatment that consists of systemic chemotherapy (CT) along with either surgery and/ or radiation therapy (RT) to maximize local tumor control3,4,5. By a multi-modality treatment strategy, the cure rate of RMS dramatically improved from only 25% to 70% in developed countries1,6.

Local disease control by surgery remains a significant obstacle in children with rhabdomyosarcoma at various anatomic sites of tumors. So, balancing local tumor control with functional and cosmetic morbidity remains a major obstacle, especially in young children. Although the extent of disease after the primary surgical procedure (Clinical Group) is correlated with outcome7. And relapses commonly occur in patients who have gross residual disease after upfront surgery or who have undergone debulking surgery8.

Radiation therapy (RT) is another local treatment modality for patients with microscopic or gross residual disease after biopsy/initial surgical resection or chemotherapy. Conventional RT remains the standard for treating patients with rhabdomyosarcoma9. Application of RT depends on the site of primary tumor, histological subtype/fusion status, postsurgical residual disease (none vs. microscopic vs. macroscopic), and presence of involved lymph nodes. The timing of RT and doses is to be clearly defined. An anesthesiologist is necessary to sedate young patients. The younger patients frequently do not get appropriate RT because of concerns about normal tissue toxicity; reduced dose is sometimes considered. Radiation techniques are to be specially designed to deliver radiation to the tumor while sparing maximum normal tissue. Considering all the challenges with RT for optimal care of RMS patients, pediatric radiation oncologists and nurses who are experienced in treating children are to be available.

Chemotherapy is a mandatory part for all children with rhabdomyosarcoma. The intensity and duration of chemotherapy are dependent on the risk group assignment10. Risk-group stratification is defined based on pre-treatment TNM staging, surgical-pathological Group (CG), and tumor histology (/*FOXO1 fusion status)6,11,12.

Risk-directed multi-modality therapy reduces treatment-related morbidity by tailoring total chemotherapy and radiotherapy doses without compromising the outcome for low-risk patients and reduces the risk of late complications related to chemotherapy and radiotherapy. And by applying more intensive therapy, we can improve the cure rate of the high-risk patients.

The National Institute of Cancer Research and Hospital (NICRH) is a tertiary-level hospital in Bangladesh, where RMS is one of the common malignancies in children. Each year, 25 to 35 children with RMS usually attend the Pediatric Hematology and Oncology department (PHO) of NICRH. Here, multi-modal treatment can be applied in a one-stop setting. But one must face diverse problems while treating rhabdomyosarcoma in children, like a limited radiotherapy facility for a lack of pediatric radiation oncologists, trained nurses, and sometimes an anesthesiologist. Other alarming issues are surgery-related. Treatment irregularity, chemotherapy toxicity, or poor response are different obstacles that affect the cure rate of RMS in children. On the above background, the study was done to see the outcome of RMS in children with risk-directed multimodal therapy and to identify the challenges while treating children.

Methodology

The prospective observational study was done in the Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Department of NICRH, Bangladesh, from January 2016 to December 2020. Children up to 18 years of age of both sexes with a definitive diagnosis of RMS were included consecutively. Information related to clinical profile, imaging reports, histopathological reports, immunohistochemistry, and post-surgical status was gathered in a pre-formed data sheet. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scans of the primary sites were done for each patient. For metastatic work-up, X-ray chest or CT scan, Bone scan, CSF study, and bilateral bone marrow aspiration and biopsy were done when indicated.

Risk-stratification of children with RMS was done for the treatment strategy into low risk, Intermediate risk, and high risk with the help of TNM staging, post-surgical Clinical Group, and tumor histology6,11. At first, disease staging was determined by the primary site and size of the tumor, presence or absence of regional node and /or distant metastases13,14. The Clinical Group (CG) was defined from the post-surgical resection status of the tumor with pathological assessment of the tumor margin and lymph node disease7,15. And tumor histology was from the pathological reports. Post-surgical resection status CG I, with no microscopic residue, was equivalent to R0 resection, which was defined from histopathological resection margin status. Gene fusion status could not be determined due to a lack of facilities in our center. The treatment protocol was followed as per the Children’s Oncology Group.

Chemotherapy

For low-risk patients, included 4 VAC cycles (total cumulative cyclophosphamide dose 4.8 g/m2) followed by 12 cycles of vincristine and dactinomycin over 46 weeks. Doses and schedule followed the COG-ARST 0331 of subset-2 for all low-risk patients (Supplementary Table E1).

For the intermediate-risk group of patients, 14 cycles of chemotherapy with the vincristine, dactinomycin, and cyclophosphamide (VAC) arm for 42 weeks and radiation therapy (RT) were delivered early at week 4. Total cumulative dose of cyclophosphamide was 16.8 g/m2 [1.2gm/m2/dose], doses were less than the previous protocol [2.2gm/m2/dose (Supplementary Table E2).

Patients with metastatic or high-risk RMS received 54 weeks of therapy. Blocks of therapy were with vincristine/irinotecan (weeks 1 to 6, 20 to 25, and 47 to 52), interval compression with vincristine/doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide alternating with etoposide/ifosfamide (weeks 7 to 19 and 26 to 34), and vincristine/dactinomycin/cyclophosphamide (weeks 38 to 46). Radiation therapy occurred at weeks 20 to 25 (primary). Early RT was considered at weeks 1 to 6 (for intracranial or paraspinal extension) and weeks 47 to 52 (for extensive metastatic sites) (Supplementary Table E3).

Complete surgical resection was recommended. If complete resection was not feasible, initial biopsy followed by neoadjuvant chemotherapy and definitive local control measures was suggested.

Radiotherapy was given using the three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy technique (3D CRT). Radiation doses were determined according to CG, histology type, and tumor site9. Timing was determined as per risk-group stratification. The recommended irradiated volume was the presurgical and prechemotherapy disease extent at diagnosis, gross tumor volume (GTV) plus 1 cm. Clinical target volume (CTV) = Gross tumor volume (GTV) + 1 cm.

Evaluation and Follow-up

Evaluation was done before radiotherapy, then after every 6 weeks of chemotherapy, and before any definitive surgical measure if biopsy or gross residue of tumor was at presentation. Follow-up was continued during the whole treatment period, as well as after treatment completion. The last follow-up was given till 30th December 2024. Challenges were identified from records of the entire treatment course that were faced sequentially by the patients. Some information was also gathered over the telephone from guardians and follow-up records of each studied child. Challenges were categorized as Surgery-related, Radiotherapy-related, Chemotherapy-associated, Disease outcome, and related to treatment regularity.

Operational definitions

For the purpose of this study, the following definitions were applied:

Combined modality treatment/ multimodality therapy – Refers to the management of children with rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) using systemic chemotherapy together with surgery, radiation therapy, or both, in order to achieve optimal local tumor control according to the scheduled timelines of the COG protocol.

Post-surgical clinical group I – Indicates complete tumor removal with no microscopic residual disease, also referred to as an R0 resection.

Irregular treatment – Defined as a delay of three or more weeks beyond the scheduled chemotherapy date.

Poor response – Applied when the primary tumor shows no change in size or less than a 25% reduction (Clinical Group III) after week-7 chemotherapy and during subsequent follow-up assessments.

Dropped out – Refers to patients who, after enrollment, have no documented trace in admission records, day-care records, or follow-up files, and who also do not respond to telephone contact.

COG – Children’s Oncology Group

EpSSG – European Pediatric Soft Tissue Sarcoma Group

3D -CRT – 3-Dimensional Conformal Radiation Therapy

GTV – Gross Tumor Volume

CTV – Clinical Target Volume

Statistical Analysis

Outcome was defined on the last follow-up date of December ’2024 as remission, relapse, refractoriness with progressive disease, death, and dropout. Dropout cases were those who could not be traced. The event-free survival (EFS) period was defined as the time from the date of enrollment to disease relapse/progression/death. Overall survival (OS) was measured from the date of enrollment until death or the last follow-up. Overall survival (OS) and event-free survival (EFS) were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The recorded data were edited and analyzed statistically using SPSS version 23.

Results

The study enrolled a total of 146 children with RMS, aged 0.33 to 17 years, with a mean of 6.1 years ± SD 4.7. Male predominant (n=86) with a Male & Female ratio was 1.4:1. (57.5% male and 42.5% female).

Clinical-pathological profiles of the disease related to prognosis have been described in Table 1. Based on the clinicopathological characteristics, the studied children were grouped as low-risk, 16.4% (n=24), intermediate-risk, 68.5% (n=100), and high-risk, 15.1%(n=22) (Table 1). Combined modality treatment could be applied in 38.5% of children only, but it was not feasible in the majority (60.3%) of cases.

Table 1. Clinico-Pathological profile

| Variable | Number (N) | Percentage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||||

| < 1 | 12 | 8.2 | ||

| ≥1 to 9 | 97 | 66.4 | ||

| ≥10 to 17 | 37 | 25.3 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 84 | 57.5 | ||

| Female | 62 | 42.5 | ||

| Site of the tumor | ||||

| Favorable site(F) | 34 | 23.3 | ||

| Unfavorable site (UF) | 112 | 76.7 | ||

| Size | ||||

| <5 cm (a) | 21 | 14.4 | ||

| ≥ 5 cm (b) | 125 | 85.6 | ||

| Nodal status (N) | ||||

| N0 | 6 | 4.1 | ||

| N1 | 47 | 32.2 | ||

| Nx | 93 | 63.7 | ||

| Metastases (M) | ||||

| M0 | 124 | 84.9 | ||

| M1 | 22 | 15.1 | ||

| Histology subtype | ||||

| Embryonal | 117 | 80.1 | ||

| Alveolar | 25 | 17.1 | ||

| Undifferentiated | 4 | 2.7 | ||

| TNM staging | ||||

| Stage 1 | 21 | 14.4 | ||

| Stage 2 | 11 | 7.5 | ||

| Stage 3 | 92 | 63 | ||

| Stage 4 | 22 | 15.1 | ||

| Clinical Group (CG) | ||||

| CG I | 2 | 1.4 | ||

| CG II | 30 | 20.5 | ||

| CG III | 93 | 63.7 | ||

| CG IV | 21 | 14.4 | ||

| COG-Inter Rhabdomyosarcoma risk group (IRSG) | ||||

| Low-risk | 24 | 16.4 | ||

| Intermediate-risk group | 1002 | 68.5 | ||

| High-risk group | 22 | 15.1 | ||

During 1st line of therapy, 74.7% (n=109/146) of children with RMS achieved remission initially with excellent chemo-responsiveness, 14.4% were refractory from the beginning, and 11% dropped out. But subsequent follow-up found progression in 12.3% after responsiveness for a certain period, relapse in 36.3% after completion of therapy, and death in 5.5% related to chemo-toxicities and or septicemia.

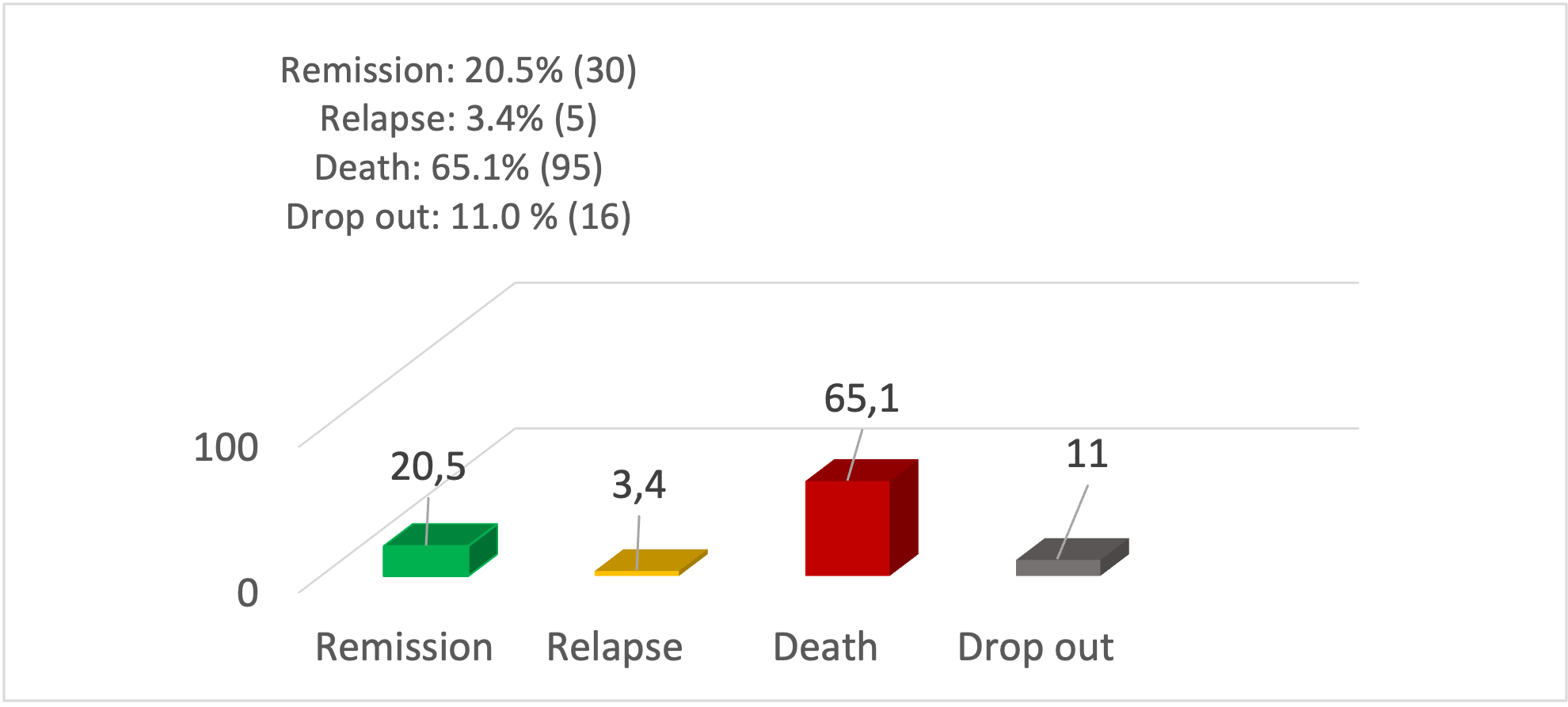

The overall outcome was measured in December 2024 (Figure 1). Complete remission was found in only 20.5% (n=30), Relapse in 3.4% (n=5), death in 65.1% (n=95), and dropout in 11.0% (n=16). Dropped out cases were 4 in number in the low-risk group, 9 in the intermediate-risk group, and 3 patients from the high-risk group. The outcome varied by patients’ risk group. From the low-risk group, 55.0% achieved remission, from the intermediate risk group, only 20.9 % achieved remission, whereas no remission was achieved from the high-risk group, but 100% died (Table 2).

Figure 1: Outcome of total enrolled children (n=146)

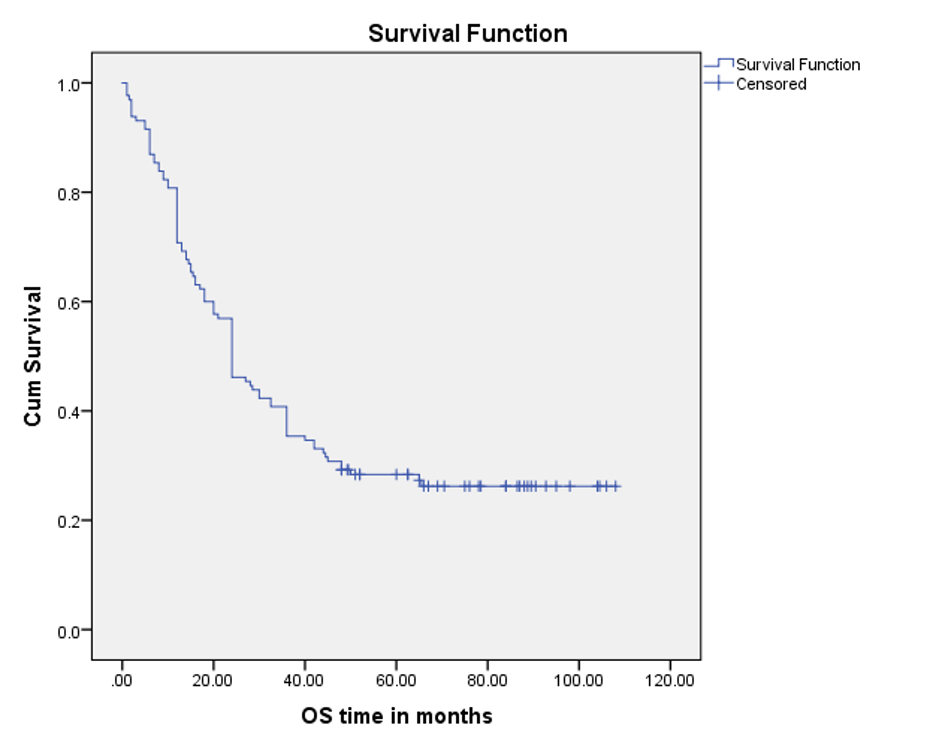

Because 16 patients could not be traced from the beginning, survival outcomes were analyzed for n=130 children by the Kaplan-Meier method. Among them, 5-year OS was found to be 26.9%.

Table 2: Outcome by Risk Group (n=130)

| Outcome/ Risk group | Remission | Relapse | Death | Total/ Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-risk | 11 (55%) | 1 (5%) | 8 (40%) | 20 (100%) |

| Intermediate-risk | 19 (20.9%) | 4 (4.4%) | 68 (74.7%) | 91 (100%) |

| High-risk | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 19 (100%) | 19 (100%) |

| Total/Percentage | 30 (23.1%) | 5 (3.8%) | 95 (73.1%) | 130 (100%) |

The mean OS time was 43.5 months ±3.5 SE (95% CI 36.4 – 50.4), and the median was 24.0 months ±2.4 SE (95% CI, 19.1 – 28.8) over a median follow-up period of 24.0 (range, 1 to 108) months (Figure 2).

Figure 2. OS curve, using the Kaplan-Meier method (n=130)

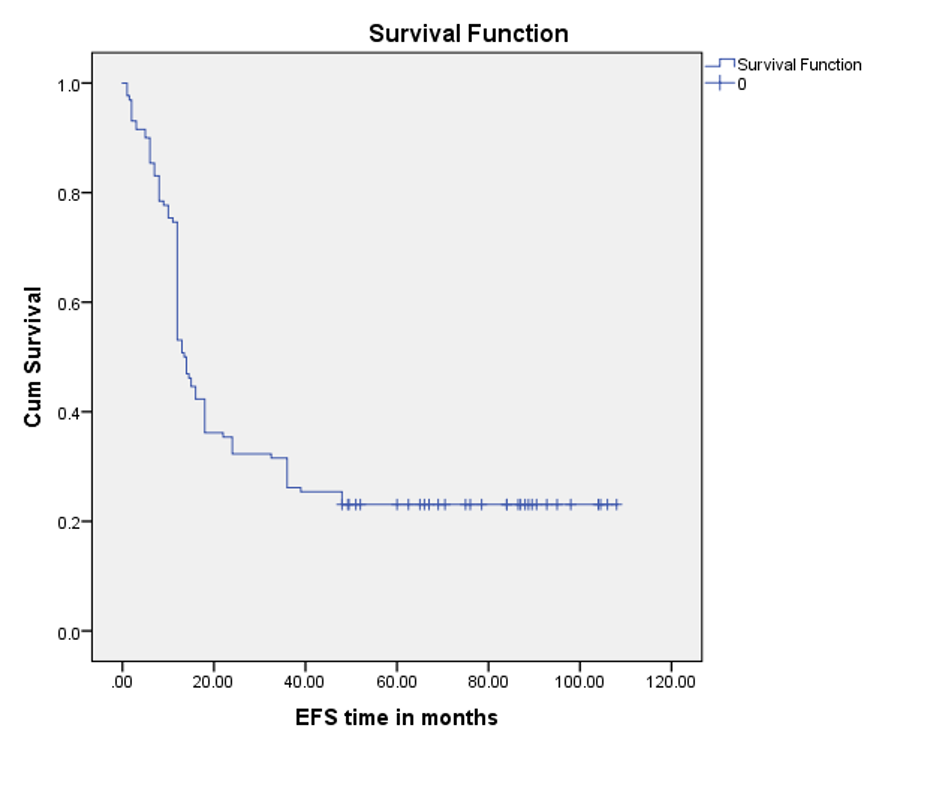

Five-year EFS was 23.1%. with mean EFS time was 36.1 months ±3.5 SE (95% CI 29.1- 43.0), and the median was 13.5 months± 0.5 (95% CI 12.3-14.6) over a follow-up of 24.0 (range, 1 to 108) months (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Event-free survival curve by Kaplan-Meier analysis (n=130)

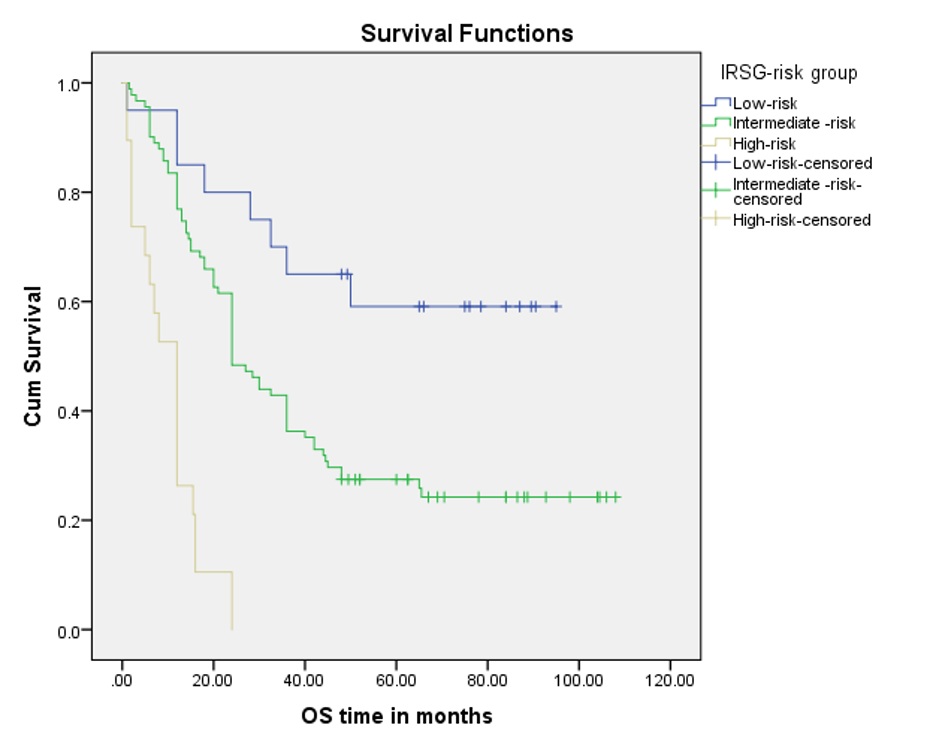

OS varied with the IRSG risk group. For the low-risk group, 5-year OS was 60%, for the Intermediate-risk group, 25.3% and 00.0% for the high-risk group (Figure 4).

Figure 4. OS curve by the Kaplan-Meier method by Rhabdomyosarcoma risk group (n=130)

Analysis of mortality (65.1%) cases revealed 32.9% were following relapse, 14.4% were for refractoriness, 12.3% following disease progression with responsiveness for some period, and 5.5% related to chemotoxicities and or septicemia.

Identified Challenges (Table 3) were diverse and multiple, related to disease outcome and treatment modalities.

Table 3. Challenges with Multi-modal treatment in children with RMS (N=146)

| Type of challenges | Number (N) | Percentage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Challenges with treatment modalities | ||||

| Surgery related | 75 | 51.4 | ||

| Surgically difficult size for R0 resection | 36 | 24.7 | ||

| Debulking surgery was done at presentation | 24 | 16.4 | ||

| Bulky tumor for R0 | 15 | 10.3 | ||

| Radiotherapy related | 38 | 26 | ||

| Too young for RT | 16 | 10.9 | ||

| RT could not be given timely manner | 22 | 15.1 | ||

| Chemotherapy related | 32 | 21.9 | ||

| Poor response | 15 | 10.3 | ||

| Chemo-toxicity | 17 | 11.6 | ||

| Disease outcome related | 116 | 79.5 | ||

| Death | 95 | 65.1 | ||

| Relapse | 5 | 3.4 | ||

| Dropped out | 16 | 11 | ||

| Treatment Pattern | ||||

| Irregular treatment | 30 | 20.5 | ||

| Non-multimodal treatment | 88 | 60.3 | ||

Challenges related to treatment modalities: Surgery-related were found in 51.4% (n=75%), such as – Debulking surgery was done in 16.4% (n=24); Surgically difficult sites for R0 resection were in 24.7% (n=36), and bulky tumors for R0 resection were in 10.3% (n=15) children.

Radiotherapy-related challenges were found in 26.0% (n=38) cases, like 10.9% (n=16) patients were young age for RT, and 15.1 % (n=22) cases, RT could not be given timely manner.

Chemotherapy-related challenges were found in 21.9% with 10.3% (n=15) poor response; 11.7%(n=17) experienced chemo-toxicities. Irregular treatment was in 20.5% (n=30). The major concern was that multi-modal treatment could not be applied to 60.3 % children with RMS.

Discussion

An overall cure rate of 70−80% was observed with current treatment regimens in high-income countries, with significant variability among various risk groups9,16. Our study found an overall cure rate of 20.5% which varied with the risk group. Cure rate was higher (55.0%) in the low-risk group than intermediate risk (20.9%), but no remission in the high-risk group.

VAC was used as the standard chemotherapy regimen in the different COG studies. The survival rate varied with the different risk groups of children in the COG studies. The COG study divided the low-risk group of patients into two subsets. For subset 1 patients, they reduced the length of therapy with a reduced dose of cyclophosphamide, and the estimated 3-year survival rate was 98% (95% CI, 95% to 99%) in low-risk patients with the VAC regimen17. In subset 2, Patients received four cycles of VAC (equivalent cyclophosphamide dose as subset 1) followed by VA over 46 weeks, and the estimated 3-year OS rate was 92% (95% CI, 83%-97%)18. The total cumulative cyclophosphamide dose was reduced compared with the previous IRS-IV study to decrease the risk of permanent infertility. Our study followed the subset-2 protocol for all low-risk groups of patients, using only a reduced dose of cyclophosphamide. Our study found a 5-year OS rate of 60.0% in the low-risk patients (Table 2 and Figure 4). The study results for low-risk RMS children are far below the COG study results of the OS rate, 92% (95% CI, 83%-97%).

The COG reported a prospective randomized trial of two treatment strategies for patients with intermediate-risk rhabdomyosarcoma with the VAC as the standard backbone regimen. Patients were randomly assigned to receive treatment with either VAC or VAC with vincristine/irinotecan (VAC/VI). Another trial of COG was to receive either VAC therapy or VAC therapy with additional courses of topotecan and cyclophosphamide. All patients received a lower cumulative dose of cyclophosphamide and earlier introduction of RT than did patients who were treated in previous COG studies. In the two different trials of COG on the intermediate risk group, 4-year OS was 73% for the VAC regimen19,20,21. Our study used VAC therapy with earlier RT, though in some cases RT was delayed up to 13 weeks, and found high mortality and relapse with a 5-year survival rate of 25.3 % which is far below the above-mentioned studies (Figure 4). The mean OS time for this group of children was 44.2 months±4.1(95% CI, 36.2 to 52.2) according to the recent study.

Another large study group, the EpSSG, used the IVA (Ifosphamide, vincristine, and actinomycin-D) regimen as backbone and performed a randomized phase III trial with the addition of vinorelbine and low-dose cyclophosphamide as maintenance chemotherapy in patients with high-risk rhabdomyosarcoma, which were classified as intermediate risk by the COG. The 5-year OS rate was 73.7% for patients without maintenance chemotherapy and 86.5% for patients in the maintenance chemotherapy group22. For the limited inpatient facilities and having socio-economic constraints, our center preferred the VAC regimen chemotherapy, as it can be given on a day-care basis.

The high-risk patients with metastatic disease continue to have a relatively poor prognosis by both the COG and EpSSG group with current therapy (5-year survival rate of ≤50%). The COG performed a pilot trial in patients with high-risk rhabdomyosarcoma and found that with a median follow-up of surviving patients of 3.8 years, survival 56% [95% CI, 46% to 66%]23. In the phase III trial, all patients received 54 weeks of chemotherapy, including VI, interval-compressed VDC alternating with IE, and vincristine/dactinomycin/cyclophosphamide. The European multinational collaboration, EpSSG, found that the 3-year OS rate was 47.9% (95% CI, 41.6%–53.9%)24. They used 4-cycle IVA with doxorubicin and then IVA for five cycles and maintenance chemotherapy with low-dose vinorelbine and oral cyclophosphamide for 1 year.

Our recent study used the COG-high risk protocol and found no survival from the high-risk group; rather, 100 % died (Figure 4). The mean OS time was 10.0 months± 1.5 (95% CI, 7.0 to 13.1) months.

In low- and middle-income countries, some studies report suboptimal OS of less than 50%25,26. In Bangladesh, a previous study found that the overall 5-year survival rate was 41.0%, which might be due to the advanced stage of the disease26. The recent study of NICRH, Bangladesh, OS rates were found to be 26.9% (95% CI 19.1% to 28.8%) over a median follow-up of 24.0 months (range,1-108). This OS rate, 26.9% which is far below the above-mentioned studies, despite the majority (65.7%) of children being in the favorable age group of ≥1 to 9 years, and mostly (80.1%) with favorable histology.

Challenges

The study tried to shed light on the various challenges faced with multimodal treatment of RMS in children, which might be responsible for the limited outcome from the existing settings of Bangladesh.

From local treatment modalities [Table 3], surgery-related challenges were in more than half of the studied children (51.4%; n=75). Although surgical removal of the entire tumor (R0) should usually be considered initially in RMS for improved outcome27,28,29. But the recent study found that 24.7% children had a tumor in a surgically difficult site for R0 resection, and 10.3% children had a bulky tumor for R0 resection. So, gross total resection with R0 could not be done in 35.0%. Moreover, 16.4% children with RMS had debulking surgery at the beginning. But debulking surgery is not recommended for patients with rhabdomyosarcoma8. It is preferable to delay definitive surgery (delayed primary excision) rather than debulking a tumor at the time of initial biopsy. And again, patients with microscopic residual tumor after initial surgery have improved prognoses if a second operation (primary re-excision) to resect the primary tumor bed before beginning chemotherapy could be done without morbidity30. All these surgical factors might limit the prognosis of the studied children.

Radiotherapy (RT) related challenges were found in 26.0% (n=38) cases, in 10.9% children, RT could not be given at a young age. And in 15.1% children, RT could not be applied as directed by the protocol schedule for a long queue in the center, and for the lockdown during the coronavirus pandemic in the year 2020-2021. The younger patients frequently do not get appropriate RT because of concerns about normal tissue toxicity. The study had 8.4% from < 1 year of age and 31.5 % ≤ 3 years. They are the patients for whom surgical resection by delayed primary excision is an important consideration. And local control rates from delayed primary excision and reduced-dose RT are equivalent to those from RT alone31.

Chemotherapy-associated challenges were found in 21.9% including poor response in 10.3% and 11.7% faced toxicities like severe neutropenia, followed by septicemia. Moreover, irregular chemotherapy was received by 20.5% children.

Outcome-related challenges: The outcome of the studied children related to a high rate of death and relapse (68.5%), along with a dropout, is a challenging and painful journey both for RMS children as well as treating physicians. The study reported death was 65.1% (n=95), which was due to relapse, refractoriness, and progression after having responded for some period.

The disease heterogeneity, lack of molecular testing facilities, evolving treatment regimens, and limited resources are some of the challenges faced by clinicians while treating a patient with RMS in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Despite these, the recent study identified other challenges, like treatment irregularities, local treatment modalities like application of radiotherapy in time and incomplete resection in the upfront surgery; poor response to chemotherapy, high mortality, and relapse are frequently faced in existing settings from resource-limited countries like Bangladesh. If these fields of challenges can be addressed for improvement, the outcome of RMS in children can be improved further in a resource-limited center like Bangladesh.

Conclusion

The study found a high rate of mortality and relapse, with a suboptimal survival rate. Major challenges with the management of RMS in children were related to local treatment modalities like surgery and radiotherapy. Treatment irregularity and dropout added more challenges.

Acknowledgements

The author and children with RMS expressed heartfelt thanks to the Children’s Oncology Group for their treatment protocol.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this manuscript.

Ethical considerations

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and/or their legal guardians before starting therapy. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

License

© Author(s) 2025.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, and unrestricted adaptation and reuse, including for commercial purposes, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

-

Supplementary files RMS (PDF/0.16MB) - Download

References

-

Gurney JG, Severson RK, Davis S, Robison LL. Incidence of cancer in children in the United States. Sex-, race-, and 1-year age-specific rates by histologic type. Cancer. 1995 Apr 15;75(8):2186-95.

-

Ries LAG, Kosary CL, Hankey BF, Miller BA, Clegg L, Edwards BK (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1973-1996, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, 1999.

-

Donaldson SS, Meza J, Breneman JC, Crist WM, Laurie F, Qualman SJ, Wharam M; Children’s Oncology Group Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee (formely Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Group) representing the Children’s Oncology Group and the Quality Assurance Review Center. Results from the IRS-IV randomized trial of hyperfractionated radiotherapy in children with rhabdomyosarcoma–a report from the IRSG. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001 Nov 1;51(3):718-28.

-

Stevens MC, Rey A, Bouvet N, et al. Treatment of nonmetastatic rhabdomyosarcoma in childhood and adolescence: third study of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology–SIOP Malignant Mesenchymal Tumor 89. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Apr 20;23(12):2618-28.

-

Donaldson SS, Anderson JR. Rhabdomyosarcoma: many similarities, a few philosophical differences. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Apr 20;23(12):2586-7.

-

Raney RB, Anderson JR, Barr FG, et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma and undifferentiated sarcoma in the first two decades of life: a selective review of intergroup rhabdomyosarcoma study group experience and rationale for Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study V. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001 May;23(4):215-20.

-

Crist W, Gehan EA, Ragab AH, et al. The Third Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study. J Clin Oncol. 1995 Mar;13(3):610-30.

-

Cecchetto G, Bisogno G, De Corti F, et al. Italian Cooperative Group. Biopsy or debulking surgery as initial surgery for locally advanced rhabdomyosarcomas in children?: the experience of the Italian Cooperative Group studies. Cancer. 2007 Dec 1;110(11):2561-7.

-

Crist WM, Anderson JR, Meza JL, et al. Intergroup rhabdomyosarcoma study-IV: results for patients with nonmetastatic disease. J Clin Oncol. 2001 Jun 15;19(12):3091-102.

-

Gupta AA, Anderson JR, Pappo AS, et al. Patterns of chemotherapy-induced toxicities in younger children and adolescents with rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee. Cancer. 2012 Feb 15;118(4):1130-7.

-

Breneman JC, Lyden E, Pappo AS, et al. Prognostic factors and clinical outcomes in children and adolescents with metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma–a report from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study IV. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Jan 1;21(1):78-84.

-

HaDuong JH, Martin AA, Skapek SX, Mascarenhas L. Sarcomas. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2015 Feb;62(1):179-200.

-

Lawrence W Jr, Gehan EA, Hays DM, Beltangady M, Maurer HM. Prognostic significance of staging factors of the UICC staging system in childhood rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study (IRS-II). J Clin Oncol. 1987 Jan;5(1):46-54.

-

Lawrence W Jr, Anderson JR, Gehan EA, Maurer H. Pretreatment TNM staging of childhood rhabdomyosarcoma: a report of the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group. Children’s Cancer Study Group. Pediatric Oncology Group. Cancer. 1997 Sep 15;80(6):1165-70.

-

Crist WM, Garnsey L, Beltangady MS, et al. Prognosis in children with rhabdomyosarcoma: a report of the intergroup rhabdomyosarcoma studies I and II. Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Committee. J Clin Oncol. 1990 Mar;8(3):443-52.

-

Gartrell J, Pappo A. Recent advances in understanding and managing pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma. F1000Res. 2020 Jul 8;9:F1000 Faculty Rev-685.

-

Walterhouse DO, Pappo AS, et al. Shorter-duration therapy using vincristine, dactinomycin, and lower-dose cyclophosphamide with or without radiotherapy for patients with newly diagnosed low-risk rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee of the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2014 Nov 1;32(31):3547-52.

-

Walterhouse DO, Pappo AS, Meza JL, et al. Reduction of cyclophosphamide dose for patients with subset 2 low-risk rhabdomyosarcoma is associated with an increased risk of recurrence: A report from the Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee of the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer. 2017 Jun 15;123(12):2368-2375.

-

Arndt CA, Stoner JA, Hawkins DS, et al. Vincristine, actinomycin, and cyclophosphamide compared with vincristine, actinomycin, and cyclophosphamide alternating with vincristine, topotecan, and cyclophosphamide for intermediate-risk rhabdomyosarcoma: children’s oncology group study D9803. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Nov 1;27(31):5182-8.

-

Hawkins DS, Chi YY, Anderson JR, et al. Addition of Vincristine and Irinotecan to Vincristine, Dactinomycin, and Cyclophosphamide Does Not Improve Outcome for Intermediate-Risk Rhabdomyosarcoma: A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Sep 20;36(27):2770-2777.

-

Casey DL, Chi YY, Donaldson SS, et al. Increased local failure for patients with intermediate-risk rhabdomyosarcoma on ARST0531: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer. 2019 Sep 15;125(18):3242-3248.

-

Bisogno G, De Salvo GL, Bergeron C, et al. European paediatric Soft tissue sarcoma Study Group. Vinorelbine and continuous low-dose cyclophosphamide as maintenance chemotherapy in patients with high-risk rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS 2005): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019 Nov;20(11):1566-1575.

-

Weigel BJ, Lyden E, Anderson JR, et al. Intensive Multiagent Therapy, Including Dose-Compressed Cycles of Ifosfamide/Etoposide and Vincristine/Doxorubicin/Cyclophosphamide, Irinotecan, and Radiation, in Patients With High-Risk Rhabdomyosarcoma: A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jan 10;34(2):117-22.

-

Schoot RA, Chisholm JC, Casanova M, et al. Metastatic Rhabdomyosarcoma: Results of the European Paediatric Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study Group MTS 2008 Study and Pooled Analysis With the Concurrent BERNIE Study. J Clin Oncol. 2022 Nov 10;40(32):3730-3740.

-

Hadley LG, Rouma BS, Saad-Eldin Y. Challenge of pediatric oncology in Africa. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2012 May;21(2):136-41.

-

Rahman ATM,Begum M, CSH Kibria et al.: Outcome of paediatric rhabdomyosarcoma attended in a tertiary care hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Bangladesh Medical Research Council Bulletin. 2020 Jun 10; 46(1):17-21

-

Leaphart C, Rodeberg D. Pediatric surgical oncology: management of rhabdomyosarcoma. Surg Oncol. 2007 Nov;16(3):173-85.

-

Lawrence W Jr, Hays DM, Heyn R, Beltangady M, Maurer HM. Surgical lessons from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study (IRS) pertaining to extremity tumors. World J Surg. 1988 Oct;12(5):676-84.

-

Lawrence W Jr, Neifeld JP. Soft tissue sarcomas. Curr Probl Surg. 1989 Nov;26(11):753-827.

-

Hays DM, Lawrence W Jr, Wharam M, et al. Primary reexcision for patients with ‘microscopic residual’ tumor following initial excision of sarcomas of trunk and extremity sites. J Pediatr Surg. 1989 Jan;24(1):5-10.

-

Rodeberg DA, Wharam MD, Lyden ER, et al. Delayed primary excision with subsequent modification of radiotherapy dose for intermediate-risk rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee. Int J Cancer. 2015 Jul 1;137(1):204-11.