Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the management of oncologic critical illness

Abstract

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has evolved from a last-resort intervention for severe cardiopulmonary failure to a viable support modality across a range of critical care contexts. Its use in oncology, however, remains controversial due to the complex interplay between malignancy, immunosuppression, coagulopathy, and resource allocation. This review analyzes the current evidence regarding ECMO application in cancer patients, focusing on clinical indications, outcomes, and decision-making frameworks. ECMO may be considered in four principal oncologic settings: rescue therapy for reversible cardiorespiratory failure, perioperative support during high-risk tumor resections, bridge-to-therapy in treatment-responsive malignancies, and selective use in post–hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) cases. Evidence suggests that cancer should be viewed as a relative, not absolute, contraindication to ECMO. Patients with solid tumors, particularly when ECMO is planned or used as a bridge to curative therapy, demonstrate survival rates comparable to non-cancer cohorts in selected studies. Conversely, outcomes are poor among those with hematologic malignancies or post-HSCT status due to profound immunosuppression and bleeding risk. Ethical and logistical challenges, including cost, futility, and proportionality of care, underscore the necessity for multidisciplinary, individualized decision-making. Advances in technology, anticoagulation management, and oncologic therapies may expand ECMO’s future role in cancer care with subsequent nursing implications.

Key words: Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, ECMO, oncology, hematological malignancy, support, bridge to therapy

Introduction

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is an evolution of classical cardiopulmonary bypass. ECMO is an advanced life support technique used for severe respiratory, cardiac, or combined cardiopulmonary failure refractory to conventional therapies1,2. Its primary goal is to oxygenate systemic venous blood and remove carbon dioxide while the failing lung or heart is allowed to recover or serve as a bridge to long-term life support therapies or transplantation3. While traditionally considered a life-saving treatment, the use of ECMO has seen a notable increase in recent decades. Data from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) international registry shows that in 2022, 16.803 ECMO procedures were performed in 557 healthcare institutions worldwide4.

A typical ECMO circuit consists of several key components: an inflow cannula that drains deoxygenated venous blood from the body, a mechanical pump that facilitates blood circulation within the system, a membrane oxygenator that removes carbon dioxide and replenishes oxygen, a heat exchanger to warm the blood as it passes through the oxygenator, and an outflow or reperfusion cannula that returns oxygenated blood to the circulation. There are two main configurations of ECMO, differentiated by the location and function of the return cannula: Venovenous (VV) and Venoarterial (VA)5,6,7.

Although the mechanics and general indications for ECMO are well understood, its use in patients with cancer remains controversial. Historically, cancer (either hematologic or solid) has been considered a relative contraindication to ECMO because of several intersecting concerns. Many oncology patients are immunocompromised (due to disease or treatment), which increases the risk of infection during extracorporeal support8,9. They often have thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy (either from marrow suppression, chemotherapy, or the malignancy itself), which raises bleeding risk during ECMO anticoagulation8,10. The underlying malignancy may limit meaningful recovery (for example, in widespread metastatic disease) and resource-utilisation ethics become relevant11. The literature is limited: small series, case reports, heterogeneous patients and no large randomized trials in oncologic cohorts. Consequently, a significant gap in knowledge remains regarding standardized selection criteria and long-term functional outcomes for this specific population. For example, a 2023 review identified only 24 retrospective/prospective/ case‐reports from 1998-2022 in cancer patients receiving ECMO8.

Given improving oncologic survival in many cancers and increasing ICU admission of oncology patients, the question arises: when (and in whom) should ECMO be considered in the oncology population? The answer lies in careful patient selection, understanding distinct settings (perioperative support, bridging to therapy, rescue for adverse event), prognostic features, and balancing risks.

The aim of this paper is to review and analyze the current evidence on the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in patients with cancer, focusing on oncologic contexts rather than general ECMO applications. It seeks to evaluate clinical indications, outcomes, and prognostic factors across different malignancies, discuss the unique complications and management challenges in this population, and explore the ethical and resource considerations surrounding ECMO use in oncology. Ultimately, the paper aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of when ECMO may be appropriate in cancer patients and to highlight the need for individualized, multidisciplinary decision-making supported by evolving clinical evidence.

Methodology

This paper was designed as a comprehensive narrative review to analyze the current evidence regarding the use of ECMO in patients with cancer. A targeted literature search was conducted using major electronic databases, including PubMed/MEDLINE and Google Scholar, to identify relevant articles published up to 2025. The search strategy employed combinations of key terms such as “Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation,” “ECMO,” “oncology,” “cancer,” “hematologic malignancy,” “solid tumor,” “stem cell transplantation,” and “bridge to therapy,” alongside “nursing care” and “ethical considerations” to capture the multidisciplinary nature of the topic.

The review prioritized literature that specifically addressed ECMO application within oncologic contexts rather than general critical care settings. Inclusion criteria included a broad range of study types, including retrospective cohorts, case series, case reports, systematic reviews, and clinical guidelines. The selection process focused on articles that provided data on clinical indications—such as rescue therapy, perioperative support, and bridging to therapy—as well as outcomes including survival rates and prognostic factors distinguishing solid tumors from hematologic malignancies. Additionally, sources discussing specific complications like coagulopathy and immunosuppression, as well as nursing implications and ethical resource allocation, were included to ensure a holistic analysis.

Given the heterogeneity of the available data and the absence of large randomized controlled trials in this population, a qualitative synthesis of the literature was performed rather than a statistical meta-analysis. The retrieved sources were analyzed to categorize findings into four principal oncologic settings: rescue therapy for reversible cardiorespiratory failure, perioperative support during high-risk tumor resections, bridge-to-therapy for treatment-responsive malignancies, and selective use in post-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) cases. This synthesis integrates recent findings on technological advances, anticoagulation management, and evolving clinical guidelines to provide an up-to-date overview of current practices and future directions.

Results

ECMO Indications in Oncology

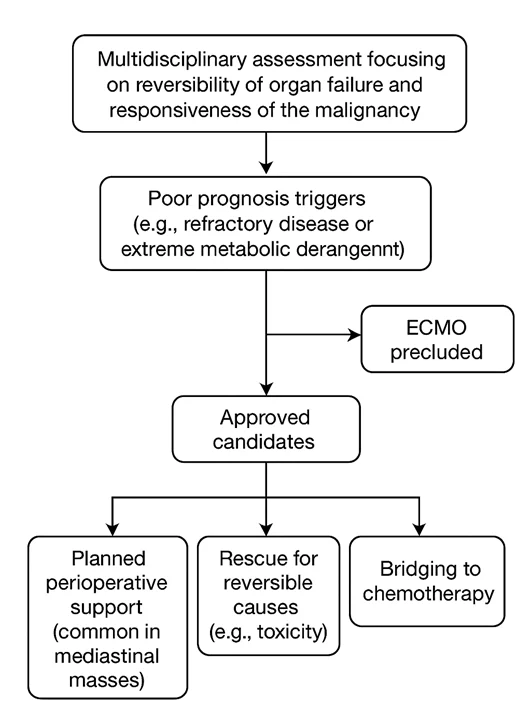

In oncology, the indications for ECMO can be broadly categorized into four main contexts. First, it may serve as rescue therapy for emergent cardiorespiratory failure in cancer patients with potentially reversible causes. Second, ECMO can be used as planned perioperative support during high-risk tumour resections where airway or cardiovascular collapse is anticipated. Third, it may act as a bridge to therapy in patients with treatment-sensitive malignancies, providing organ support until definitive oncologic treatment can be initiated. Lastly, ECMO has been attempted as support in the post-haematopoietic stem cell transplantation or hematologic malignancy setting, although outcomes in this group remain considerably poorer and its use is more controversial. Figure 1 presents a conceptual framework for ECMO decision-making in oncology, illustrating a multidisciplinary assessment that weighs reversibility of organ failure and malignancy responsiveness, excludes patients with poor prognostic features, and stratifies eligible candidates into planned perioperative support, rescue for reversible causes, or bridging to oncologic therapy, with highly selective use in hematologic or post-HSCT patients.

Figure 1: ECMO indications and decision-making in oncology

The decision process begins with a multidisciplinary assessment focusing on the reversibility of organ failure and the responsiveness of the malignancy. “Poor Prognosis” triggers (such as refractory disease or extreme metabolic derangement) generally preclude ECMO. Approved candidates are stratified by context: planned perioperative support (common in mediastinal masses), rescue for reversible causes (e.g., toxicity), or bridging to chemotherapy. Use in hematologic/Post-HSCT patients remains highly selective due to poorer historical outcomes.

Respiratory or cardiac failure in patients with active malignancy

One of the common triggers for ECMO in cancer patients is acute respiratory failure (or combined cardiopulmonary failure) that is refractory to conventional mechanical ventilation or circulatory support. This can occur in both hematologic and solid tumour patients8. For instance, in hematologic malignancies, acute respiratory failure is a frequent ICU admission cause9.

Peri-operative ECMO support in tumour surgery

In patients with large mediastinal masses or thoracic malignancies undergoing resection (which may entail high risk of airway collapse or hemodynamic compromise), ECMO (or extracorporeal lung/heart support) has been used in a planned manner8. A review of mediastinal disease suggests that large anterior mediastinal tumours with risk of airway/vascular compression may benefit from either pre-cannulation or intraoperative ECMO support10.

Bridge to therapy and adverse events management

Another important setting is where ECMO is used for bridging to chemotherapy or other oncologic treatments of a critically ill oncology patient to definitive therapy. For example, in a patient with severe cardiopulmonary compromise from a therapy‐sensitive tumour, ECMO may allow stabilization while chemotherapy is instituted. A case report described ECMO in a patient with metastatic non‐seminomatous germ cell tumour to allow chemotherapy delay12.

Also, an emerging application of ECMO is the management of chemotherapy-related side effects. Chemotherapeutic agents can have cardiac or pulmonary toxicity, which may limit their use in clinical practice. Shah reported the case of a 45-year-old patient with severe respiratory failure after bleomycin administration who did not respond to high doses of steroids. The patient was supported with VV-ECMO and was successfully weaned from mechanical ventilation after 3 days13.

ECMO can play a role in the management of severe, life-threatening complications arising from chemotherapy, particularly when these toxicities cause reversible cardiac or respiratory failure. While ECMO does not treat chemotherapy-related side effects directly, it serves as a temporary life-support system that allows time for organ recovery or for the toxic effects of chemotherapy to subside. ECMO has been used in cases of chemotherapy-induced cardiomyopathy, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) from drug toxicity or infection during neutropenia12,14, and tumour lysis syndrome15. In such scenarios, ECMO provides circulatory and respiratory support, maintaining oxygenation and perfusion while the underlying condition is managed with medical therapy, drug withdrawal, or detoxification. Thus, ECMO can be considered a bridging therapy that stabilizes critically ill oncology patients experiencing severe chemotherapy-related side effects until recovery of organ function is possible.

Post‐hematopoietic stem cell transplantation support

Patients who have undergone HSCT for hematological malignancies may experience severe and often life-threatening complications such as ARDS, graft-versus-host disease, or septic shock. In these critical situations, ECMO has been employed as a salvage therapy when conventional management fails to achieve adequate oxygenation or hemodynamic stability. However, outcomes in this subgroup remain significantly poorer compared to other oncologic populations. The combination of profound immunosuppression, persistent cytopenias, increased susceptibility to infection, and limited capacity for organ recovery contributes to high mortality rates. Current evidence therefore supports a highly selective approach to ECMO in post-HSCT patients, reserved only for cases with clearly reversible pathology and favorable prognostic indicators9,16,17.

Outcomes and prognostic factors

The key issue for the oncologic population is: what are the outcomes if ECMO is used, and what features predict better or worse survival? Several recent reviews give insights, though limitations exist. While the absolute survival rates remain lower in oncology patients than in the general ECMO population, they are not uniformly hopeless. Some highly selected patients—especially with solid tumours, treatment‐sensitive disease, planned ECMO support, and minimal metabolic derangement at ECMO initiation—can achieve survival to hospital discharge and even long‐term oncologic remission. Conversely, patients with hematologic malignancies, post-HSCT, or with refractory/progressive disease have much poorer outcomes, and ECMO may be futile.

Outcomes in oncology patients

A 2023 review of 24 studies found that ECMO may be considered as salvage support in specific cancer patients, like solid tumour with respiratory failure, perioperative support, and bridging to therapy, but in hematologic oncology undergoing HSCT, there was no clear benefit8. A recent retrospective cohort of 342 adult ECMO patients (2017-2023), 40 of whom had cancer (92.5% solid tumour), found 90-day mortality 70 % for cancer patients vs 56.8 % for non‐cancer patients (difference p=0.087, i.e., not statistically significant). In multivariable analysis, cancer status did not reach statistical significance (HR 1.41, p=0.114). Important prognostic factors identified included hyperlactatemia (>10 mmol/L) and hypoalbuminemia (<2.4 g/dL)18. Outcomes vary widely across studies. A review on ECMO‐related adverse events in adult cancer patients noted long-term survival rates for solid tumours around 26-32 % and for hematologic malignancies, with mortality of 50-100 % in small series11.

In children with cancer, a systematic review and meta-analysis (625 patients identified, approx half with data) found pooled mortality during ECMO around 55 % and in‐hospital mortality about 60 % (range 25-93 %)19. A Swedish national retrospective study of 958 children with hematologic malignancy identified 12 (1.3 %) who required ECMO; 8 survived ECMO, 7 survived the ICU period, and 6 survived the underlying malignancy. The authors concluded ECMO may be considered in children with hematologic malignancy20.

Table 1. Comparative Outcomes: Adult vs. Pediatric Oncology and ECMO

| Category | Adult Population Data | Pediatric Population Data |

|---|---|---|

| Survival Outcomes | Cancer patients showed a 90-day mortality of 70% vs. 56.8% in non-cancer patients [8]. Long-term survival for solid tumors is approximately 26–32%11. | Patients have a pooled in-hospital mortality of 60% [19]. In a Swedish pediatric cohort, 50% survived their underlying malignancy 20. |

| Clinical Indications | Adult uses include perioperative support for mediastinal masses , rescue for chemotherapy toxicity , and bridging for treatment-responsive tumors8,10. | Pediatric uses include support during HSCT or immune effector cell therapy, neuroblastoma rescue , and tumor lysis syndrome15,16,20. |

| Hematologic Malignancies | Outcomes are generally poor, with 32% survival to hospital discharge and 61% mortality while on support9. | While high-risk, ECMO is considered a viable salvage therapy in selected pediatric hematologic cases20. |

| Prognostic Factors | Significant predictors in include hyperlactatemia (>10 mmol/L) and hypoalbuminemia (<2.4 g/dL)18. | Outcomes are inferior to the general pediatric ECMO population20. |

Prognostic factors

From the available evidence, several prognostic factors have been identified that influence outcomes in cancer patients supported with ECMO. Type of malignancy is among the most significant determinants—patients with solid tumours generally demonstrate better survival compared to those with hematologic malignancies or those treated post-haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), where mortality remains high due to severe immunosuppression and treatment-related complications8,9. The extent and status of malignancy also play a pivotal role: patients with progressive or refractory disease tend to have poor outcomes, as demonstrated in studies where solid tumour patients with active progression had minimal survival benefit from ECMO8. Furthermore, pre-ECMO metabolic derangements and illness severity strongly correlate with prognosis. Elevated lactate levels (>10 mmol/L) and hypoalbuminemia (<2.4 g/dL) have been shown to independently predict higher mortality in ECMO patients, including the cancer subgroup18. The timing and planning of ECMO initiation are equally crucial; elective or perioperative use during thoracic malignancy surgery yields better outcomes than emergency ECMO deployment in decompensated patients8, 10. Finally, bleeding and infectious complications remain major prognostic challenges, as immunosuppression, chemotherapy-induced cytopenia, and coagulopathy increase susceptibility to hemorrhage and sepsis, both of which significantly worsen outcomes9. Currently, standard ECMO prognostic scores (e.g., RESP or SAVE) have not been consistently validated in oncology cohorts, and no dedicated malignancy-specific scoring system exists.

Table 2. Key prognostic factors and their reported impact on ECMO outcomes in oncology patients

| Prognostic factor | Reported impact on outcome |

|---|---|

| Malignancy type | Patients with solid tumors generally demonstrate better survival compared to those with hematologic malignancies. Post-HSCT status is associated with significantly poorer outcomes. |

| Disease status | Progressive or refractory disease is associated with minimal survival benefit. Conversely, treatment-sensitive disease predicts better survival outcomes. |

| Lactate levels | Pre-ECMO hyperlactatemia (>10 mmol/L) is an independent predictor of higher mortality. |

| Albumin levels | Hypoalbuminemia (<2.4 g/dL) is independently associated with increased mortality. |

| Timing of initiation | Planned or perioperative use yields better outcomes than emergency rescue. Timely initiation before severe multiorgan failure improves survival chances. |

| Hematologic status | Low platelet count has been identified as an adverse prognostic factor. |

| Complications | The occurrence of hemorrhage or sepsis during support significantly worsens outcomes. |

Special considerations in oncology

Solid tumour versus hematologic malignancy

The clinical outcomes of ECMO in oncology vary considerably depending on the underlying malignancy. Patients with solid tumours tend to demonstrate more favorable responses, particularly when ECMO is used in carefully selected contexts such as perioperative support during resection of large mediastinal or thoracic masses, or as a bridge to therapy in cases of reversible respiratory or cardiac failure secondary to tumour burden. The 2023 review by Teng et al. reported meaningful survival in such settings, emphasizing that early, planned ECMO intervention—rather than emergency initiation—can optimize outcomes in these patients8, 10.

In contrast, hematologic malignancies pose a far greater challenge. These patients often suffer from profound immunosuppression, thrombocytopenia, and prolonged neutropenia, either as a result of their disease or following HSCT. Consequently, they are more susceptible to bleeding and infectious complications, which significantly compromise ECMO efficacy. The available literature consistently demonstrates mixed to poor outcomes in this group. For instance, a multicentre review found that only approximately 32% of patients with hematologic malignancies survived to hospital discharge, while 61% died while on ECMO support9. Evidence to date remains insufficient to justify routine ECMO use in post-HSCT patients or those with uncontrolled or refractory hematologic disease.

In pediatric oncology, ECMO use appears somewhat more promising, though outcomes remain inferior to those in non-oncologic children. A comprehensive meta-analysis reported that while ECMO is technically feasible in this population, mortality remains higher than in the general pediatric ECMO cohort, underscoring the importance of rigorous patient selection and multidisciplinary evaluation before initiation19.

Perioperative support for tumour resection

Large mediastinal masses (e.g., thymomas, large lung cancers, neurogenic tumours in the posterior mediastinum) pose specific risks: airway compression, venous return obstruction, and hemodynamic collapse upon induction of anaesthesia. A review in 2023 of mediastinal disease management emphasizes that patients at high risk should be identified via imaging/postural symptoms/pulmonary function, and multidisciplinary planning is needed for ECMO support (most often veno‐arterial) during induction/maintenance of surgery10,21. Another recent case series in lung adenocarcinoma found the use of veno‐venous ECMO as a bridging to diagnosis and therapy. The key is planned ECMO rather than rescue initiation after collapse, because the latter is associated with worse outcomes22.

Bridging to oncologic therapy

The notion of using ECMO to stabilise patients with life‐threatening organ failure so that they can receive cancer therapy (chemotherapy, targeted therapy) is gaining traction. For instance, in one report, a patient with an advanced non‐seminomatous germ cell tumour and cardiopulmonary failure was placed on veno‐arterial‐venous (VAV) ECMO to permit chemotherapy, leading to recovery12. The review by Teng et al. also noted cases of ECMO as a supportive means for chemotherapy in hematologic tumour patients8. A large retrospective study of 297 cancer patients with severe respiratory failure found that overall survival following VV- ECMO was poor, with a 60-day survival rate of 26.8%. Adverse prognostic factors included low platelet count, elevated lactate, and progressive or newly diagnosed malignancy, and no significant survival advantage was seen compared to similar patients not treated with ECMO23.

Ethical, clinical, and logistical considerations

The use of ECMO in oncology presents not only clinical but also profound ethical and logistical challenges. Resource allocation remains a major consideration, as ECMO is an exceptionally resource-intensive therapy requiring specialized equipment, dedicated ICU capacity, high nurse-to-patient and physician ratios, and substantial use of blood products. In patients with advanced or refractory malignancy and limited likelihood of recovery, the appropriateness of initiating ECMO raises important ethical questions regarding futility and proportionality of care. Current evidence, however, indicates that cancer should be viewed as a relative rather than an absolute contraindication to ECMO, emphasizing individualized assessment rather than categorical exclusion8,11. ECMO serves as an effective treatment option for individuals experiencing circulatory and/or pulmonary failure. Nevertheless, for patients with hematological malignancies, the results of ECMO treatment have been notably unfavorable. Therefore, it is recommended to exercise caution when determining the appropriateness of ECMO for these patients24.

Careful patient selection is therefore paramount. Given the higher baseline risks of bleeding, infection, and poor physiological reserve, selection criteria must integrate oncologic and critical care perspectives. Relevant variables include tumour status (remission versus progressive disease), presence of metastases, anticipated reversibility of organ failure, performance status, and expected efficacy of ongoing or planned oncologic therapy. Several institutions have proposed structured decision-making algorithms, particularly for cases involving mediastinal masses or high-risk thoracic oncologic surgery, to aid in determining when ECMO may be justified.

Bleeding and thrombosis pose additional challenges. Many cancer patients exhibit complex coagulopathies, thrombocytopenia, or are receiving anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy, rendering anticoagulation management during ECMO highly delicate. These patients are consequently at greater risk for both catastrophic bleeding and circuit thrombosis, complicating overall management. Similarly, infection risk is amplified in oncology populations due to disease- or therapy-induced immunosuppression, leading to higher rates of ECMO-associated sepsis, which can negate potential survival benefits9.

Given the uncertainty surrounding outcomes, initiation of ECMO in cancer patients should always follow a multidisciplinary decision-making process, involving intensivists, oncologists, cardiothoracic surgeons (where perioperative), perfusionists, and critical care teams. Open and transparent discussions with patients and families are essential, focusing on potential reversibility, realistic survival probabilities, and expected post-ECMO quality of life. Finally, evidence suggests that timely initiation—before the onset of severe multiorgan failure, extreme hyperlactatemia, or profound hypoalbuminemia—may be associated with improved outcomes, further underscoring the importance of early, proactive evaluation rather than delayed rescue intervention18.

Practical and management issues

When ECMO is utilised in oncology patients, several practical and management issues require attention.

Pre-cannulation evaluation

When evaluating ECMO candidacy in oncology patients, a comprehensive assessment is essential, including review of oncologic status (cancer type, stage, metastatic burden, treatment responsiveness, curative vs palliative intent, and disease status such as newly diagnosed versus relapse/progression). Organ function (respiratory, cardiac, renal, hepatic) must be evaluated, as multi-organ failure worsens prognosis, alongside hematologic and coagulation status (platelet count, INR/PTT, fibrinogen, DIC parameters, recent chemotherapy, neutropenia). Metabolic derangements such as high lactate, low albumin, and high vasopressor requirements indicate poor prognosis and should be considered. For perioperative ECMO, anatomical risks, including airway or vascular compression, and pulmonary function tests are critical. A multidisciplinary team involving oncology, ICU, cardiothoracic surgery, perfusion, and anesthesia should be engaged to conduct a risk-benefit discussion that addresses resource implications and patient/family values to ensure appropriate, ethical decision-making16,25,26.

Cannulation and ECMO modality

The choice of ECMO modality in oncology patients should be guided by the underlying type and severity of organ failure. VV ECMO is typically employed for isolated respiratory failure, whereas VA ECMO is indicated for combined cardiac and respiratory compromise. In select cases, particularly when bridging to oncologic therapy, hybrid configurations such as veno-arterial-venous (VAV) ECMO have been successfully utilized in oncology patients to provide both respiratory and circulatory support8,12. For perioperative support, especially in patients with mediastinal masses at high risk of airway or cardiovascular collapse, VA ECMO is often cannulated prior to induction of general anaesthesia to maintain hemodynamic stability10,21. Careful pre-procedural planning is essential, including consideration of local anaesthesia for cannulation in high-risk cases and ensuring the multidisciplinary team is prepared for rapid escalation if complications arise.

Anticoagulation and hemostasis

Oncology patients often present with thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), or recent chemotherapy, significantly elevating the risk of bleeding during ECMO support27. Consequently, standard anticoagulation protocols may require adaptation, such as employing lower anticoagulation targets, more frequent monitoring, and stricter transfusion thresholds. Proactive transfusion management is essential, with the administration of platelets, fibrinogen, red blood cells, and plasma as needed to address coagulopathy and support circulatory function28. Despite these measures, the risk of circuit-associated thrombosis persists, even with reduced anticoagulation levels, necessitating vigilant monitoring and timely intervention. Balancing the risks of bleeding and thrombosis is particularly challenging in oncology ECMO patients, underscoring the need for individualized management strategies and close interdisciplinary collaboration29.

Infection control

In oncology patients undergoing ECMO, meticulous aseptic technique is paramount due to the elevated risk of bloodstream infections, cannula-site infections, and sepsis. This heightened susceptibility arises from factors such as neutropenia, immunosuppressive therapies, and the presence of indwelling devices. Implementing strict infection control measures, including the use of antimicrobial dressings and adherence to aseptic protocols, is essential to mitigate these risks30.

The routine use of prophylactic antimicrobials remains a topic of debate. Some studies suggest that while prophylactic antibiotics may reduce the incidence of infections in certain patient populations, their routine use in ECMO patients is not universally recommended. Tailoring antimicrobial therapy based on local microbiological patterns and individual patient risk factors is crucial to avoid unnecessary antibiotic exposure and resistance31.

Early identification of infections is critical. Monitoring biomarkers such as procalcitonin can aid in distinguishing bacterial infections from other causes of inflammation. Elevated PCT levels have been associated with bacterial sepsis, making it a valuable tool in the early detection and management of infections in ECMO patients32.

Oncologic therapy integration

In bridging scenarios, close collaboration with the oncology team is essential to determine whether chemotherapy or targeted therapy can be safely administered during ECMO, accounting for potential drug interactions and organ dysfunction. Case reports indicate that bridging to chemotherapy is feasible in selected patients8,12. For perioperative ECMO, coordination of surgery timing, cannulation strategy, and postoperative oncologic care—including radiation or additional chemotherapy—is critical. Clinicians must also recognize that ECMO may prolong ICU stay and potentially delay oncologic treatment, necessitating careful weighing of ECMO benefits against alternative management strategies11.

Weaning and decannulation

While standard ECMO monitoring and management apply, in oncology patients, it is essential to continuously assess not only recovery of organ function but also the feasibility of continuing oncologic therapy, expected survival, and quality of life. If organ recovery is limited or the underlying malignancy is found to be refractory, early multidisciplinary discussions regarding futility or withdrawal are crucial to prevent prolonged, non-beneficial ECMO support. Studies have shown that early withdrawal decisions are often based on perceived futility, with factors such as the patient’s prior wishes, suffering, and medical futility being commonly cited reasons for withdrawal of VA-ECMO33 . Additionally, a study found that 19% of health records referred to the “futility” of further treatment, highlighting the importance of clear communication and decision-making in these complex cases34.

Ethical and resource considerations

ECMO is a high-cost, resource-intensive therapy typically available only in specialized centers, and its use in oncology patients requires careful consideration of expected benefit, patient wishes, resource allocation, and potential futility. Guidelines, such as those from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO), list immunosuppression as a relative contraindication, a category that often includes cancer patients8. Initiating ECMO in patients with widely metastatic or treatment-refractory disease may prolong suffering with minimal chance of meaningful recovery, underscoring the need for clear goals-of-care discussions. Conversely, denying ECMO solely based on malignancy may withhold potential benefit in selected cases, such as young patients with chemo-sensitive tumors and reversible organ failure. Many centers, therefore, adopt institutional criteria emphasizing multidisciplinary decision-making, pre-ECMO oncology assessment, and periodic review of ECMO continuation. As oncologic therapies improve and survival increases, historical automatic exclusion of cancer patients from ECMO may need reevaluation; recent data suggest that cancer status alone is not independently predictive of mortality in adult cohorts18.

Complications and considerations for oncology patients on ECMO

Oncology patients on ECMO are at elevated risk for several complications due to both their underlying malignancy and its treatment. Bleeding is a common concern, arising from thrombocytopenia, recent chemotherapy, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), or marrow involvement. Hemorrhage can occur at cannula or surgical sites, particularly during perioperative ECMO, and may also originate from the extracorporeal circuit itself8,9.

Infection risk is heightened due to neutropenia, immunosuppressive therapy, central lines, and the extracorporeal circuit, predisposing patients to bloodstream infections, fungal infections, and sepsis. Even with minimized anticoagulation, thrombosis and embolic events remain a concern, as circuit clotting or systemic emboli can occur, and prophylaxis is complicated by concurrent bleeding risk. Additionally, multiorgan dysfunction—including hepatic, renal, and cardiac impairment from prior chemotherapy, tumor burden, or previous treatments—can complicate ECMO management and recovery. Prolonged ICU stay further increases vulnerability to ICU-acquired weakness, delirium, nosocomial infections, and pressure injuries, which may be more severe in the frail oncology population. Survivors require careful assessment of oncologic status and functional recovery. Notably, some reports indicate meaningful long-term oncologic survival after ECMO, particularly in pediatric patients or those with chemotherapy-sensitive tumors11,20. Rehabilitation, follow-up care, and coordination with oncology teams are therefore essential.

Additional tumor-related complications may interact with ECMO dynamics. These include tumor lysis syndrome, massive pulmonary metastases, and airway or vascular compression from mediastinal masses. Case reports describe ECMO use in the setting of tumor lysis syndrome, highlighting its potential as a bridging therapy in carefully selected patients. Finally, quality of life and functional outcomes must be considered; even if survival is achieved, the long-term oncologic trajectory, including risk of recurrence or metastasis, should inform decisions regarding ECMO initiation8.

Nursing care considerations

Nursing care is central to the safe and effective management of oncology patients receiving ECMO. Nurses play a pivotal role in monitoring, early detection of complications, coordination of multidisciplinary care, and supporting both patient and family during a complex ICU course35.

Hemodynamic and circuit monitoring

Nurses must continuously monitor ECMO circuit parameters, including flow rates, pressures, oxygenation, and anticoagulation levels, to detect early signs of circuit dysfunction, clot formation, or oxygenator failure. Oncology patients often have fragile vasculature and coagulopathies, so careful observation for bleeding at cannula sites or spontaneous hemorrhage is essential. Frequent laboratory monitoring of hemoglobin, platelets, fibrinogen, coagulation profile, and lactate is critical to guide transfusions and anticoagulation adjustments35,36.

Infection prevention and sepsis surveillance

Given the high risk of infection in immunocompromised oncology patients, meticulous aseptic technique during line and circuit care is imperative. Regular assessment of cannula sites, strict hand hygiene, and adherence to central line protocols help minimize bloodstream infections. Nurses should monitor for early signs of sepsis, including fever, hypotension, rising inflammatory markers, or altered mental status, and communicate promptly with the critical care and oncology teams to initiate timely interventions35,36,37.

Bleeding and thrombosis management

Balancing anticoagulation to prevent circuit clotting while minimizing bleeding risk requires vigilant nursing assessment. Nurses should inspect for ecchymoses, oozing at cannula sites, mucosal bleeding, and monitor for hematuria or gastrointestinal bleeding. Accurate documentation and timely reporting of bleeding or clotting events are crucial for prompt medical decision-making35,36,37.

Organ support and multisystem care

Oncology patients on ECMO often have underlying organ dysfunction due to chemotherapy, tumor burden, or prior treatments. Nursing care includes optimizing renal function through careful fluid management and dialysis coordination, monitoring hepatic function, and supporting ventilator management in VV ECMO. Nurses also assess neurologic status, skin integrity, and nutritional needs, which are essential for recovery and prevention of ICU-acquired complications35,36.

Rehabilitation and functional support

Early mobilization, physical therapy, and positioning are important even during ECMO support to reduce ICU-acquired weakness, pressure injuries, and delirium. Nurses coordinate rehabilitation efforts with physiotherapists and occupational therapists while balancing safety concerns related to cannulas and circuit integrity38.

Psychosocial support

Oncology patients and their families face heightened emotional stress during ECMO. Nurses serve as liaisons, providing clear explanations, emotional support, and updates on clinical status. They also facilitate discussions regarding goals of care, treatment expectations, and advance directives in collaboration with the multidisciplinary team35,36.

Coordination with oncology and critical care teams

Nurses help integrate ECMO care with ongoing oncologic treatment, including chemotherapy, radiation, or surgical interventions, ensuring timing, dosing, and organ support are optimized. Multidisciplinary communication is vital to adapt care plans based on patient condition, treatment response, and evolving goals of care39.

Future research

The evidence currently available is largely limited to retrospective, single-center studies with small sample sizes, which restricts the generalizability of findings. Furthermore, significant heterogeneity in patient selection and cancer types across institutions complicates direct comparisons. Future directions and research needs in ECMO use for oncology patients focus on addressing the limited and heterogeneous data currently available. Key priorities include establishing larger observational cohorts or registries with detailed subgroup analyses—distinguishing solid versus hematologic malignancies, perioperative use versus bridging to therapy, and planned versus rescue ECMO initiation. Prospective or registry-linked studies are needed to identify prognostic markers specific to oncology patients on ECMO, such as lactate, albumin, and tumor status, which can help develop decision-making algorithms. Refining selection criteria through validated risk-stratification tools that incorporate oncologic prognosis, organ failure severity, coagulopathy, immunosuppression, and reversibility likelihood is crucial. Research should also evaluate economic and quality-of-life outcomes beyond survival, focusing on functional status, oncologic trajectory, and cost-effectiveness of ECMO in this population. Optimizing management protocols tailored to challenges like anticoagulation in thrombocytopenic patients, infection prophylaxis in neutropenic patients, and coordination of oncologic therapies during ECMO is essential. Additionally, ethics and policy research must explore how malignancy influences ECMO allocation decisions and whether institutional guidelines are warranted. Finally, technological advances that yield less invasive ECMO circuits with lower anticoagulation requirements may favorably shift the risk–benefit balance in oncology patients, warranting ongoing evaluation.

Conclusion

ECMO is no longer universally contraindicated in patients with cancer. Instead, it has emerged as a selective salvage therapy. Specifically, evidence suggests ECMO should be reserved for patients presenting with reversible organ failure, treatment-responsive malignancies, absence of multiorgan failure, and carefully selected solid tumor cases.

Clinical decision-making regarding ECMO candidacy in cancer patients should not automatically exclude individuals based on their cancer status alone. Instead, decisions should be made through multidisciplinary evaluation that incorporates prognostic factors such as tumor type and stage, severity of organ failure, and metabolic derangements. Ultimately, the development of validated, oncology-specific risk-stratification scores is urgently needed to standardize this process.

Given the evolving landscape, further research is essential to refine clinical guidelines, optimize ECMO protocols, and better assess cost-effectiveness within this specialized population. When assessing an oncology patient for ECMO, critical considerations include whether the underlying malignancy is curable or controllable, the reversibility of organ failure, the patient’s baseline functional and oncologic status, and the manageability of associated risks such as bleeding and infection. Defining clear, realistic goals for ECMO, whether as a bridge to therapy, perioperative support, or rescue, is crucial to ensure judicious and ethical application of this technology in cancer care.

Nurses play a critical role in the management of oncology patients on ECMO, bridging complex critical care with oncologic support. Their vigilance in monitoring hemodynamics, coagulation, infection, and organ function, combined with patient advocacy, psychosocial support, and coordination of multidisciplinary care, is essential for optimizing outcomes. Given the high-risk nature of this population, oncology ECMO nursing requires advanced expertise, meticulous attention to detail, and continuous assessment to balance life-sustaining therapy with patient safety, quality of life, and evolving goals of care.

Licence

© Author (s), [2026].

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, and unrestricted adaptation and reuse, including for commercial purposes, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

References

-

von Bahr V, Hultman J, Eksborg S, et al. Long-Term Survival in Adults Treated With Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Respiratory Failure and Sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(2):164-170.

-

Hackmann AE, Masood MF. The patient guide to heart, lung, and esophageal surgery. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons; 2018.

-

Gajkowski EF, Herrera G, Hatton L, et al. ELSO Guidelines for Adult and Pediatric Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Circuits. Asaio J. 2022;68(2):133-152.

-

Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO). International summary and reports [Internet]. Ann Arbor (MI): ELSO; [cited 2026 Jan 22].

-

Squiers JJ, Lima B, DiMaio JM. Contemporary extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy in adults: Fundamental principles and systematic review of the evidence. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152(1):20-32.

-

Tijmes FS, Fuentealba A, Graf MA, et al. An Overview of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Applied Radiology. 2024;53(1):22-34.

-

Glowka L, Popescu WM, Patel B. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in thoracic surgery: A game changer!. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2024.

-

Teng X, Wu J, Liao J, Xu S. Advances in the use of ECMO in oncology patient. Cancer Med. 2023;12(15):16243-16253.

-

Tathineni P, Pandya M, Chaar B. The Utility of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in Patients With Hematologic Malignancies: A Literature Review. Cureus. 2020;12(7)e9118.

-

Bertini P, Marabotti A. The anesthetic management and the role of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for giant mediastinal tumor surgery. Mediastinum. 2023;7:2.

-

Filho RR, Joelsons D, de Arruda Bravim B. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in critically ill patients with active hematologic and non-hematologic malignancy: a literature review. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1394051.

-

Chishti EA, Marsden T, Harris A, Hao Z, Keshavamurthy S. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation to Facilitate Chemotherapy-Moving the Goalposts! Cureus. 2022;14(9):e29576.

-

Shah A, Pasrija C, Kronfli A, et al. Veno-Venous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Use in the Treatment of Bleomycin Pulmonary Toxicity. Innovations (Phila). 2017;12(2):144-146.

-

Lee SW, Kim YS, Hong G. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as a rescue therapy for acute respiratory failure during chemotherapy in a patient with acute myeloid leukemia. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9(2):133-E137.

-

Aidynbek Z, Kakenov E, Mironova O, et al. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in the Management of Tumor Lysis Syndrome in Children: A Review of Cases. J Clin Med. 2025;14(8):2771

-

Di Nardo M, Ahmad AH, Merli P, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in children receiving haematopoietic cell transplantation and immune effector cell therapy: an international and multidisciplinary consensus statement. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022;6(2):116-128.

-

Williams FZ, Vats A, Cash T, Fortenberry JD. Successful Use of Extracorporeal Life Support in a Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Patient with Neuroblastoma. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2018;50(1):61-64

-

Li JJ, Chan HF, Lin MH, Tsai HE, Chen FH. Real world data: Survival outcomes and risk factors in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation use of cancer patient. Cardiology. 2025:1-29.

-

Slooff V, Hoogendoorn R, Nielsen JSA, et al. Role of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in pediatric cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Intensive Care. 2022;12(1):8.

-

Ranta S, Kalzén H, Nilsson A, et al. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Support in Children With Hematologic Malignancies in Sweden. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2021;43(2):272-275.

-

Wherley EM, Gross DJ, Nguyen DM. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the surgical management of large mediastinal masses: a narrative review. J Thorac Dis. 2023;15(9):5248-5255.

-

Luo X, Zhang J, Pan J, et al. Advancements in diagnosis and treatment of lung adenocarcinoma patients under ECMO support: a case series and comprehensive literature review. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2025;20(1):154.

-

Kochanek M, Kochanek J, Böll B, et al. Veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (vv-ECMO) for severe respiratory failure in adult cancer patients: a retrospective multicenter analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2022;48(3):332-342.

-

Cho S, Cho WC, Lim JY, Kang PJ. Extracorporeal Life Support in Adult Patients with Hematologic Malignancies and Acute Circulatory and/or Respiratory Failure. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;52(1):25-31.

-

Han JJ, Swain JD. The Perfect ECMO Candidate. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(10):1178-1182.

-

Hurley C, Di Nardo M, Rees M, et al. New perspectives on extracorporeal life support: expert teams and precise selection of candidates are transforming pediatric cancer and hematopoietic cell transplantation care. Front Oncol. 2025;15:1588403.

-

Olson SR, Murphree CR, Zonies D, et al. Thrombosis and Bleeding in Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) Without Anticoagulation: A Systematic Review. ASAIO J. 2021;67(3):290-296.

-

Pacheco-Reyes AF, Plata-Menchaca EP, Mera A, et al. Coagulation management in patients requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support: a comprehensive narrative review. Ann Blood. 2024;9:14.

-

Rintoul NE, McMichael ABV, Bembea MM, et al. Management of Bleeding and Thrombotic Complications During Pediatric Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2024;25(7):66-77.

-

Lv X, Han Y, Liu D, et al. Risk factors for nosocomial infection in patients undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2024;19(11):0308078.

-

Orso D, Fodale CM, Fossati S, et al. Do patients receiving extracorporeal membrane-oxygenation need antibiotic prophylaxis? A systematic review and meta-analysis on 7,996 patients. BMC Anesthesiol. 2024;24(1):410.

-

Gopalakrishnan R, Vashisht R. Sepsis and ECMO. Indian J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;37(2):267-274.

-

Godfrey S, Sahoo A, Sanchez J, et al. The Role of Palliative Care in Withdrawal of Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Cardiogenic Shock. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61(6):1139-1146.

-

DeMartino ES, Braus NA, Sulmasy DP, et al. Decisions to Withdraw Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Support: Patient Characteristics and Ethical Considerations. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(4):620-627.

-

Parrett M, Yi C, Weaver B, et al. Nursing Roles in Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Am J Nurs. 2024;124(11):30-37.

-

Sharma V, Joshi M. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Nursing Care. J Card Crit Care TSS. 2024;8(3):129-133.

-

Costa N, Henriques HR, Durao C. Nurses’ Interventions in Minimizing Adult Patient Vulnerability During Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation as a Bridge to Lung Transplantation: An Integrative Review. SAGE Open Nurs. 2024;10:23779608241262651.

-

Jividen RA. ECMO and nurse-led mobilization. Am Nurs J. 2024;19(2).

-

Bennetts JD, Williams TD, Beavers CJ, et al. The cardio-oncology multidisciplinary team: beyond the basics. Cardiooncology. 2025;11(1):69.